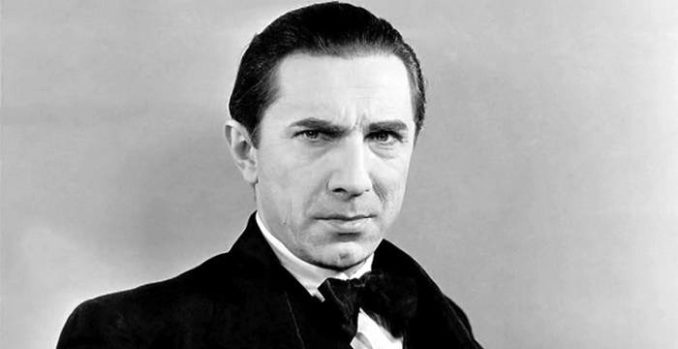

Béla Lugosi: actor, union leader, anti-fascist

Hungarian actor Béla Lugosi was crowned “Hollywood’s Prince of Darkness” for his portrayal of the vampire Count Dracula in several films. But today few people know he was a union leader and anti-fascist who fought real-life monsters.

From actor to activist

Lugosi was born Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó on Oct. 20, 1882, in Lugos, Kingdom of Hungary, Austria-Hungary (now Lugoj, Romania), 50 miles from the castle of Vlad III (Vlad Dracula). The young Lugosi was drawn to the arts. He expressed his theatrical aspirations to his father, a conservative banker, who rejected his son’s career choice. Already a rebellious spirit, Lugosi ran away from home to follow his dreams at 12.

After working at odd jobs and as a miner and machinist, Lugosi made his stage debut at age 20 in 1902, adopting the stage name Béla Lugosi the following year. Critics called him “the Laurence Olivier of Hungary,” and he was invited to join the National Theatre of Budapest.

During World War I, Lugosi enlisted in the Austro-Hungarian Army and obtained the rank of captain in the 43rd Division Ski Patrol. He was injured during combat. Once his service was completed, he returned to acting.

As the cinema gained popularity as an art form, Lugosi starred in some of Hungary’s early silent films. He remained in the National Theatre until 1918 when he answered the call for workers’ revolution.

Daily existence in Hungary was a nightmare few could escape. Lugosi had long protested the low wages, exploitative working conditions and unfair treatment of young actors. He soon recognized the contributions artists could make to political struggles.

Hungary: supporter of 1919 revolution

Lugosi supported the Hungarian Communist Party, which was founded in December 1918, and its leader, Béla Kun. Following the example of revolutionary Russia, a mass uprising overthrew the old regime beholden to the ruling class. The Hungarian Soviet Republic was founded on March 21, 1919.

While the Red Flag of the fledgling republic waved over the parliament building for only 133 days, Kun’s government introduced the first legal protections for ethnic minorities, the 8-hour workday and higher national wages.

Lugosi led a demonstration of actors in March 1919 and emerged as a high-profile organizer. He was instrumental in founding the Free Organization of Theatrical Employees, which later expanded into the first film actors union in the world, the National Trade Union of Actors.

Don Rhodes wrote in “Lugosi: His Life in Films, on Stage and in the Hearts of Horror Lovers” that “Lugosi helped combine the Free Organization of Theater Employees and members of the film industry in the National Trade Union of Actors, and acted as its general secretary.”

The NTUA’s first statutory congress began on April 17, 1919. Lugosi’s speech included the words: “Half a year ago, I launched the struggle with the decision that the national trade union of socialist actors should be established.” (Arthur Lenning, “The Immortal Count: The Life and Films of Béla Lugosi”)

Among Lugosi’s articles published in “Szinészek Lapja” (“The Actor’s Page”) was one that discussed the exploitation of actors: “The former ruling class kept the community of actors in ignorance by means of various lies, corrupted it morally and materially, and finally scorned and despised it for what resulted from its own vices. The actor, subsisting on starvation wages and demoralized, was often driven, albeit reluctantly, to place himself at the disposal of the ruling class. Martyrdom was the price of enthusiasm for acting.”

The dreams of a new nation were short-lived when the Hungarian Soviet Republic was overthrown on Aug. 6, 1919. Historian Eugen Weber, author of “Varieties of Fascism: Doctrines of Revolution in the Twentieth Century,” described the successive government as the “highly conservative rule of aristocratic cabinets headed mostly by great landed magnates.”

As a brutal “White Terror” backlash swept the country, Lugosi fled to Vienna and worked in Germany’s motion picture industry with a stint in Berlin. He then emigrated to the United States in December 1920.

Meanwhile, in Hungary thousands of Communists and Jewish people were imprisoned, tortured and/or murdered. The Communists led a precarious existence underground and emerged only after the Red Army entered Hungary in 1944.

U.S.: union organizer, voice against fascism

After docking in New Orleans, Lugosi learned English and went to New York where he continued acting. In 1927, he originated the role of Count Dracula in the Broadway stage version of Bram Stoker’s novel. In 1931, he reprised the role in a film adaptation, making him an international star.

During the Great Depression, Lugosi played an active role in the Screen Actors Guild. As a SAG founding member, he served on the union’s advisory board. Lugosi organized for the union on the set of “The Raven,” which co-starred Boris Karloff, a SAG member who was famous for portraying Frankenstein’s monster, in 1935.

By World War II, Hungarian dictator Miklos Horthy allied with Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. In opposition, Lugosi helped form the Hungarian-American Council for Democracy, calling for “Nazism to be wiped out everywhere.”

As a member of American-Hungarian Relief Inc., Lugosi was a keynote speaker at an Aug. 28, 1944, rally in Los Angeles. He demanded Washington rescue Hungarian Jewish refugees, pressure Horthy’s Nazi-puppet regime and easing immigration restrictions.

Dr. Rafael Medoff and J. David Spurlock wrote, “He may have portrayed savage villains on the silver screen, but in real life Béla Lugosi raised his voice in protest against the savage persecution of the Jews in his native Hungary.” (Jewish Ledger, Jan. 3, 2011)

Years of typecasting led to fewer roles for Lugosi. The lack of income, combined with a morphine addiction brought on by physical ailments, left him nearly destitute. Lugosi died at his Los Angeles home on Aug. 16, 1956. He was buried in one of his “Dracula” capes.

Lugosi is best remembered for his work in leading and supporting roles in over 100 films. But his contributions to the struggle for workers’ rights and the anti-fascist cause must be remembered as part of his enduring legacy.

Additional sources: Stephen J. Lee, “European Dictatorships 1918-1945.”