Reform and revolution

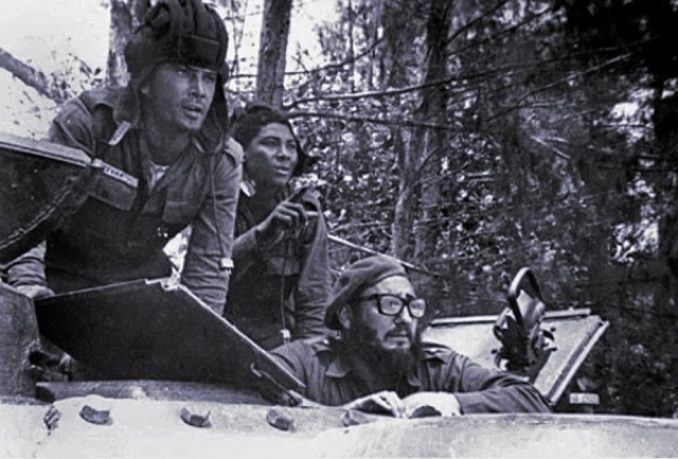

Cuba turns back Bay of Pigs invasion. Fidel explained, how in that forgotten area of small, impoverished coastal villages, the revolution had brought education and dignity to the people for the first time. They were not going back.

This article about the Cuban Revolution by Workers World Party founder Sam Marcy first appeared in the WW issue of Feb. 17, 1994.

What has made the Cuban Revolution unique? Why is it such a beacon to the workers and oppressed masses, not only of Latin America and the Caribbean but around the world?

There have been many uprisings, guerrilla wars, progressive electoral victories and military coups in Latin America in the course of this century. But the triumph of Fidel Castro’s guerrilla army over the Batista dictatorship did something that no previous struggle had accomplished.

It broke up the old state apparatus. The revolution did not merely change governing groups, as had happened so many times before. It unseated the bourgeoisie itself from its role as the ruling class by demolishing its instrument of rule, the bourgeois state.

It once again proved the monumental words of Karl Marx on the Paris Commune: that one of the fundamental characteristics of a change of class structures is the crushing of the old state apparatus and its replacement by a new state based on the popular consent of the masses.

This is what happened in Paris in 1871, when popular revolutionary committees took over the functions of government. Such committees of the urban masses had first appeared in the French Revolution of 1789, when the bourgeoisie had to call out the workers and artisans to be able to completely uproot the old feudal order. In 1871, the popular committees or communes appeared again, but this time they represented the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie.

In Cuba, the Committees in Defense of the Revolution became the eyes and ears of the new class power and its most important line of defense against U.S. imperialist sabotage and invasion. The bourgeoisie especially scorned and maligned the CDRs because they were the living proof that a new type of state, based on the workers, had taken over in Cuba in 1959.

Political revolution in Mexico

It is instructive to compare this to the Mexican Revolution of 1910-1917 which, for all its great achievements, did not go beyond progressive, bourgeois democratic reforms. It did, of course, expropriate the big land owners and distribute much of the land. This is a great revolutionary measure in the struggle against the big land holders, both feudal and capitalist. But it is not a socialist measure.

The history of peasant rebellions in both Europe and Latin America demonstrates that they ultimately deteriorate. The landlords eventually lay their hands again on the best and most fertile areas, and the struggle continues until another round of revolutionary peasant uprisings.

Peasant uprisings alone, even if they have some working-class support, do not abolish the basis of landlord and capitalist exploitation.

The Mexican Revolution was a political revolution that reformed the state. This explains why Mexico today, despite all its historically important great reforms, is a bourgeois country. Different groupings may hold the governing positions, even at the summits of power, but this does not change the class structure of society.

The imperialists themselves recognize that such reforms do not alter the character of their exploitation. They have cynically described their relations with Mexico in its revolutionary period as “continuing to do business during alterations.” Even when Mexico nationalized the lands of the foreign oil companies in the 1930s, its relationship with the U.S. continued more or less as before.

The Cuban Revolution came more than 40 years after the Mexican Revolution. It came after the great October socialist revolution in Russia and the revolutions in China, Vietnam and Korea. The industrial development of Cuba was greatly advanced compared to some other areas of Latin America, despite the constraints imposed by imperialist control and ownership — and the poverty and underdevelopment of much of the countryside.

Why Cuban Revolution went further

While Cuba had not reached the level of the European capitalist states, the objective basis for socialist revolution had matured there. It must always be remembered that Cuba lives in the shadow of U.S. finance capital, which until the revolution controlled its most important economic arteries.

Liberal writers in the U.S., some of them very well-meaning, spread confusion about the socialist revolution in Cuba. Some of it was actuated by friendly desires not to cast Cuba in communist revolutionary colors, for fear of giving aid to imperialism.

Projecting a moderate image of Cuba seemed necessary in order to withstand the utterly unprecedented vileness of the imperialist press and the increasingly shrill calls by the most extreme elements for intervention. It continued even in the face of a possible nuclear confrontation between the U.S. and Cuba over the latter’s alliance with the USSR.

Many liberal and socialist elements in the U.S. closely studied the Cuban Revolution. Probably the best account was by Leo Huberman and Paul Sweezy in the book “Cuba: Anatomy of a Revolution” (Monthly Review Press, 1960). While the Cuban leaders at that time spoke of the revolution only in terms of specific reforms, Huberman and Sweezy had “no hesitation” in concluding that “the new Cuba is a socialist Cuba.”

In the United States, the discussion of the class character of the Cuban Revolution came to a rather abrupt end when Comrade Fidel Castro, in a speech made just as CIA planes were bombing Cuba during the April 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion, for the first time put it quite explicitly: “What the Yankee imperialists will not forgive is that we have made a socialist revolution right under their very noses.”

Strong unions and Communist Party

It’s important to note that before the rise of the 26th of July Movement that launched the revolutionary struggle for power, Cuba had for many years had a strong Communist Party and trade unions that survived years of repression. The early liberal and progressive literature in the United States about the Cuban Revolution often overlooked this. But objective and subjective conditions in Cuba had matured to the point where a strong Communist Party was possible.

Mexico in 1910 did not have the conditions for the existence of a revolutionary working-class party. There were no communist parties yet in existence anywhere.