50 years ago Black GIs at Fort Hood jailed for protesting riot-control duty

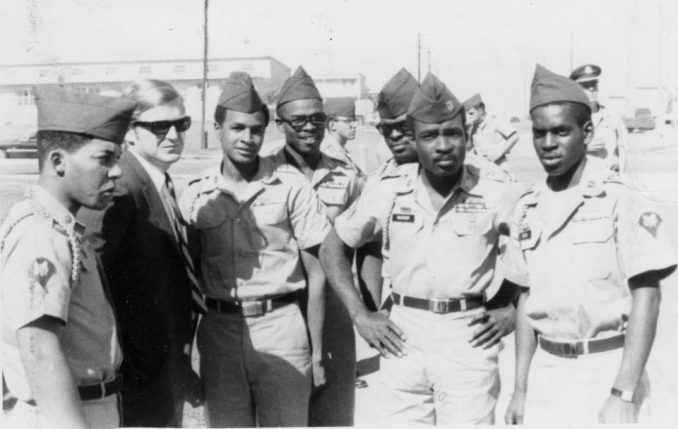

From left, PFC Ernest Bess, attorney Michael Kennedy, PFC Guy Smith, SP4 Albert Henry, PVT Ernest Frederick, SGT Robert Rucker, and SP4 Tollie Royal. The six GIs faced a general court-martial for the Aug. 23, 1968 gathering. Fort Hood, Texas.

Anger radiated through the barracks in 1968 as orders reached the Black troops of the 1st Armored Division that they would be sent to Chicago on riot-control duty at the Democratic National Convention.

GIs spread a message throughout Fort Hood, Texas, on Aug. 23: They would meet on the grassy area at the main intersection of the fort to start an all-night discussion.

More than 100 African-American GIs showed up to plan what to do. It was more than a rap session. It was a protest. To the generals and colonels whose orders must be obeyed, it was mutiny.

Some of the GIs had won medals for bravery. Some had been wounded. After a year of heavy combat in Vietnam, the fed-up Black troops were outraged at being ordered to occupy African-American neighborhoods in Chicago.

The near-uprising at Fort Hood followed rebellions at two military prisons in Vietnam that August 50 years ago. It was another sign that the Pentagon faced a serious problem that rank-and-file servicemen and servicewomen were refusing to cooperate with the war against Vietnam or play a repressive role against Black rebellions within the United States.

The following are excerpts from an article and a letter in the Sept. 18, 1968, issue of The Bond, the monthly newspaper of the American Servicemen’s Union, reporting on these events. The ASU had been founded nine months earlier to organize GIs to fight imperialist war and racism from within the U.S. military.

Black GIs at Fort Hood Refuse ‘Riot Control’

Fort Hood, Texas — Mass resistance by Black GIs here has shaken the Army. On the night of August 23 nearly a hundred Black GIs massed at a main intersection on the post in protest against being used as a part of so-called “riot control” — actually repression of their own people. (Fort Hood troops were being ordered to Chicago.) They refused to leave the intersection in spite of the pleas of their commanding general.

At dawn, 43 were arrested. The men began gathering at 9 p.m. on Friday, August 23, at 65th and Central to protest the use of federal troops in Chicago and to protest against racism. When news of the mass protest reached the startled ears of General Boles of the first Armored Division, he came out personally at about midnight to plead — not to order but to plead — with the men to disperse. They refused.

Then, fearing the massive support that these protesters had from the rank and file throughout the post, the nervous general said that they could stay there all night without repercussions. He even raised his right hand and swore to this concession with eight other brass hats (eight colonels) as witnesses, but he refused to sign a paper to that effect as suggested by some of the men. The men stayed.

At 5:45 a.m., Lt. Col. Kulo, the post provost marshal, announced: “I want you all to go back to the barracks.” They did not leave.

At 5:58 a.m., Kulo threatened: “I’m asking you to leave now. Otherwise MPs will take you in.”

The bugle sounded. Sixty MPs marched up and took 43 men away for “failure to report” (for reveille) — Article 86. In the stockade while the men were waiting to contact lawyers, they were asked if they wanted chow. Since they wanted to hold all moves until they had arranged to see lawyers, they didn’t go.

MPs were then marched in and the captain told [the Black soldiers] to get up and go to the mess hall. Nobody moved. The demand was for lawyers first. The MPs were then unleashed: punching, hitting the seated men with their nightsticks. Several men were injured and were refused medical help.

Then the Army tried the soft sell: providing cigarettes, food and beds. But the demand was still, no move until legal aid was allowed. A GI who had received a decoration for heroism in Vietnam was suffering from a kidney problem caused by wounds. He was denied medical care. Another member of the group was also denied medical attention at this time.

Eight of the men have been charged with violation of Article 90 (disobeying a legal order), which calls for a general court-martial [for serious charges with sentences greater than six months]. Thirty-four are facing a special court-martial. One was acquitted.

Legal help was arranged by the American Servicemen’s Union. Lawyers for the general courts-martial are being provided by the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee and the Workers Defense League. The 34 special courts-martial defendants are being represented by attorneys from the NAACP Legal Fund.

Statement of a Black GI at Fort Hood

Ironically, 43 men are to stand trial here at Fort Hood, Texas, for refusing riot duty in Chicago and 43 men will probably be tried and convicted. Ironical because it is Fort Hood that should be on trial and not 43 disgruntled Black soldiers.

First, I would like to say that the policy of “Equal Rights and Opportunity” as outlined by the Army Regulations has broken down here at Fort Hood as usual due to human elements. These men as well as I are very much aware of the racial inequity that has existed here and this should be considered a part of what they are protesting.

Take for example “Riot Control Training,” as important as it is, is a big joke because it is itself an addition to the problem. For weeks in class I listened to white first and second lieutenants assail the Negro rioters [in 100 cities following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.] as filthy mouthed punks and hoodlums who under the leadership of a self-styled Messiah such as a Rap Brown or Leroi Jones had brought this country close to anarchy.

No one seemed to be aware of any real facts or vaguely familiar with the findings by the “President’s Commission on Racial Disorder”? No one made any attempt to explore the possible causal relation between rioting and the understandable hatred that has mounted as a result of social and economic deprivation.

I as well as others was tired of hearing nasty words to describe my brothers, but no nasty words used to describe their situation. I agree my people are raising plenty of hell about being treated so badly, but don’t expect me to go to Chicago with a bunch of white guys who after some of our classes are understandably under the impression that “we must stop the barbarians.” …

The Houston Chronicle, Tuesday, Sept. 3, made reference to our usage of the clinched fist as a symbol of sympathy for these soldiers who are to be tried. Don’t get me wrong, we are with them all the way but our fists have been up for months. …

As for going to Chicago — simply out of the question.

By a Black Soldier Co. B, 1st Bn. 41st Inf. 2nd Armored Div. Fort Hood, Texas.

Catalinotto is author of “Turn the Guns Around: Mutinies, Soldier Revolts and Revolutions,” World View Publishers, New York, 2017.