Vietnam, August 1968: GIs in military prisons rebel

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of GI uprisings in two military prisons in Vietnam during the U.S. war there, Workers World presents the following article based on material from Catalinotto’s book, “Turn the Guns Around: Mutinies, Soldier Revolts and Revolutions” (2017).

“The month of August 1968 witnessed two of the largest prison rebellions of the Vietnam War period, both led by Black GIs,” wrote GI historian Dave Cortright in his book, “Soldiers in Revolt.” These rebellions took place among troops in Vietnam at the Da Nang Marine brig and in the military prison known as Long Binh Jail.

The GIs — that is, the members of the U.S. Armed Forces — called the latter prison LBJ, a not-so-friendly allusion to then U.S. President Lyndon Baines Johnson.

That August, I was one of a handful of people doing volunteer work out of a small office on Fifth Avenue and 21st Street in Manhattan, trying to organize a union in those armed forces. Most of the volunteers had recently finished their stint in the Army and were as strong opponents of U.S. militarism as any Lower East Side anarchist.

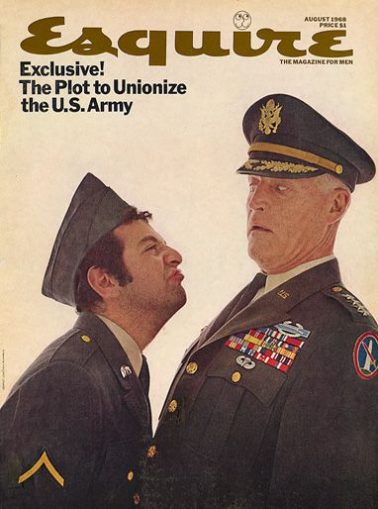

Political events in the preceding few months had increased the reach of our four-page monthly union newspaper, The Bond, from a few hundred in January 1968 to about 5,000. Our effort to form the American Servicemen’s Union was featured on the cover of the August Esquire magazine, based on an interview with ASU chairperson Andy Stapp.

Earlier in 1968, the Vietnamese uprising called the Tet Offensive had shown much of the U.S. population that the war was probably unwinnable for the U.S. LBJ was forced to announce at the end of March that he would not run for re-election. A few days after that announcement, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, and rebellions broke out in Black neighborhoods in 100 U.S. cities.

These events impelled rapid changes in the consciousness of the troops, especially African-American troops.

The ASU looked for ways to support the prison revolts in Vietnam, despite its lack of funds and forces. GIs in these prisons who were ASU members wrote letters to The Bond and other GI publications about the rebellions, providing eyewitness accounts. Here are excerpts from a Sept. 18, 1968, article in The Bond, based on some of those letters and other articles on the prison revolts:

Jailed men in Vietnam rebel against officers

“The anger of EMs imprisoned in Vietnam by the Brass has exploded. Men fed up with military oppression have rebelled at both the Marine brig at Danang and at the Army stockade at Long Binh, twelve miles north of Saigon.

“On the night of August 16, [1968,] Marine prisoners at the Danang brig tore the place apart and burned a cellblock. Angry at the humiliating requirement that they call the guards ‘sir’ and at the poor food, the overcrowding and the long delay before trials, they decided to stand up and fight back. It took a force of MPs firing shotguns to crush the rebellion among the 228 unarmed men. Seven prisoners and an MP were reported wounded. And it still wasn’t over.

“Two days later a second rebellion broke out when the officer in charge of the brig, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Gambardella, ordered some of the prisoners moved out. This time MPs had to use tear gas to stop the uprising.

“Chairman of the American Servicemen’s Union Andy Stapp immediately called the Pentagon and demanded names of the men involved. Speaking to ASU Chairman Stapp, Lt. Col. Ludvig, director of Marine Public Relations, refused to release any information to the ASU or to the American people.

“Stapp said in a press release, ‘The Brass does not want brought to light the rotten and abusive conditions that they have foisted upon the enlisted personnel in the Armed Forces.’

“In a statement to the New York Post of August 20, Stapp said, ‘We have nineteen union members in Danang and we suspect that at least some of them are involved in the uprising.’

“GI prisoners in Long Binh, the Army’s biggest stockade in Vietnam, broke out in rebellion. Long Binh Jail (known to GIs as the ‘LBJ’) was also overcrowded — there were 719 men where there were supposed to be only 550 — with angry GIs whose grievances were probably much like those of their brothers at Danang.

“Shortly before midnight on Aug. 20, an apparent fight among the prisoners in a barbed-wire enclosed medium security section brought three guards running inside to quell it. They didn’t come out. The GIs inside had grabbed them and their keys. When the three guards didn’t come out, an outside guard blew his whistle.

“At the same time, a band of prisoners rushed the gate between the medium security section and the recreation and administration area in the main part of the compound. They broke through. They then proceeded to burn down the building, which contained all their records, and nine other large buildings.

“When the Brass, commanded by Colonel William Brandenburg of Elloree, S.C., sent in MPs armed with M16 assault rifles, bayonets and tear gas grenades, the unarmed GIs inside fought back. They wounded five MPs and put the acting warden of the jail in the hospital. One GI prisoner gave his life in the brief but bitter struggle and 59 were listed as wounded.”

A group of prisoners at LBJ sent a collective letter to The Bond after reading the above article. We published the letter in the Oct. 16, 1968, issue. As you can see from the letter, publication in the newspaper and dissemination inside the prison of both articles spread solidarity and strengthened those rebelling.

Report from Long Binh Jail

“Today my man from New York managed to smuggle into the compound your Sept. 18 issue of your dynamite thing, The Bond. Your paper was thoroughly read by most of my fellow prisoners; speaking for those who read it, including myself, we would all like to say thanks for everything you are doing to further the ASU and bring to the attention of GIs all over the world the many injustices, inhumanities perpetrated on servicemen by the U.S. Government Armed Forces judicial system — particularly the Army.

“Cited here are a few case histories of prisoners that I think would be of interest to men in the Armed Forces everywhere.

“Case 1 — An infantryman just out of the field was caught stealing a peanut butter and jelly sandwich from his base-camp mess hall. First offense — sentenced to six months hard labor in LBJ.

“Case 2 — An infantryman after serving ten months of his twelve-month tour was given an order by a second lieutenant for him and the 17 other men in his element to assault a 250-man fortified North Vietnamese Army force, and was severely wounded in his right leg, right arm and kidney while the rest of his element was completely eliminated. After recuperation in Japan his medical record was lost by the U.S. Army and he was refused further medical therapy and was returned to the Republic of Vietnam without a profile for further combat duty.

“Upon reassignment, this man was charged with missing three formations and the misuse of a government vehicle (a 15-minute trip to the PX). This was a first offense. He is now on a pre-trial confinement in LBJ awaiting a special court-martial.

“Case 3 — (my own case) — I am an infantryman, not by choice but by force of the U.S. Army. My own political and personal beliefs will not allow me to carry a weapon in the field. My company was going to a heavily VC-infested area on a three-day operation. Being that I don’t carry a weapon I refused to go.

“My company commander ordered two fellow GIs to hold me while he tried to bind my legs and arms with ropes and to forcefully take me on the operation. Not being a fool and with no other course to take, I went AWOL. After being apprehended I was threatened by the Brass in my unit that I would be killed. I am now in LBJ on pre-trial confinement awaiting a general court-martial for this act, which I know was right.

“We could go on forever with many similar cases but the Brass here at LBJ will not afford us with ample stationery. We feel a great need and desire for this to be published in your next issue of The Bond. If this is possible it would be deeply appreciated by everyone in the Long Binh Stockade both Black and white.

“We would like to do more to further the cause of the ASU but at this time our hands are tied by the Brass in LBJ.

“[Signed] The inmates, Mike Rouch, Tommy McDonnel, R.C. Brown, Brien M. Schulik, Marcy Schuman, Dave Landry, J.A. Epriam.”

News reports as late as Sept. 24, a month after the big Long Binh Stockade rebellion, tell of a group of a dozen Black GIs still bravely holding out against the Brass in part of the prison.

Catalinotto’s book, “Turn the Guns Around,” also includes an account of how, later that August 50 years ago, the rebellion of the Black GIs came home to Fort Hood, Texas.