India: Farmers march for rights, win concessions

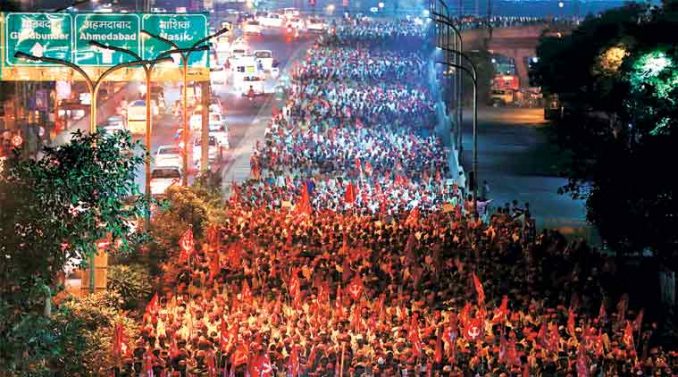

Since the beginning of March, Indian farmers have been making themselves heard, and their voices are hard to ignore. Tens of thousands of farmers in the state of Maharashtra, in western India, gathered on March 6, for the start of the “long march,” from Nashik to Mumbai, the state capital and India’s financial and commercial center.

Numbering about 50,000 by the time they arrived six days and some 112 miles later, they raised several key demands to support India’s beleaguered small farmers. The demands included a complete waiver from crippling loans, adequate minimum support prices for their produce, adequate compensation for failed crops, individual and community land rights for forest dwellers, and adequate pensions.

Some of the farmers’ demands are already law but remain unenforced or underenforced. Some demands arose from election promises that were never fulfilled. Yet other demands stem from recommendations of a 14-year-old government report by the National Commission on Farmers.

As they approached Mumbai, the Kisan (“farmer”) Long March drew a lot of attention and public support throughout India and beyond. The state government appeared to have agreed to most or all of their demands, promising to resolve problems within six months. Organizers and protesters were cautiously optimistic of the success of their action.

The march was largely organized by the All India Kisan Sabha, and an umbrella alliance called the Bhoomi Adhikar Andolan (Movement for Land Rights), with agricultural workers mainly affiliated with leftist parties like the Communist Party of India (Marxist).

Vijoo Krishnan, a leading AIKS organizer, framed the victory in Maharashtra as part of “an uprising of the agrarian sector, and it has been happening for the last two years. It has been happening in many parts of the country.” (News18India, March 13)

There have also been other labor struggles among farmers in the states of Rajasthan, in the north, bordering on Pakistan, and Uttar Pradesh, to the northeast, bordering on Nepal, and tea plantation workers around Darjeeling. In November, farmers held massive, nationwide strikes demanding reforms just before the Parliament’s winter session.

70 years post-independence, plight of rural workers hasn’t changed

Seven decades after independence from Britain, the plight of India’s rural workers, still the majority of the country’s workforce, has not changed much. While India has experienced some high levels of growth in recent decades, it has been very uneven, benefitting the small elite, while much of the population, which now numbers about 1.35 billion people, still find living a daily struggle.

Farmers often become trapped in debt, as they borrow money to farm tiny plots of land and see little in return for their toil. In recent decades, reports of high rates of suicide among Indian farmers, struggling to provide for their families, have become common. One official statistic suggests 3,097 farmers committed suicide in 2015. Many others simply give up farming, move to cities in search of work and become exploitable cheap labor for other industries.

The Bharatiya Janata Party, a right-wing political party, promotes Hindu nationalism and promises business-friendly development. The BJP marginalizes religious and ethnic minorities, as well as Dalits and other lower castes, Adivasis (Indigenous) and others.

Since coming to power, the BJP has exacerbated the nationwide crisis of the agricultural poor, especially with its land acquisition ordinance. Land acquisition in India refers to the displacement of local populations and land owners for the “developmental needs of the country.”

In reality, the government offers inadequate compensation for the displaced people, while the ordinance is a great boon to large corporations. The recent fightback by farmers and the farmers’ victory in Maharashtra may mean trouble for the BJP-led government in upcoming elections at both national and state levels.

A change in the elected government will, at best, only ease the crisis facing farmers, whose problems have been decades in the making. During most of those years, Indian politics have been dominated by the Congress Party, BJP’s main electoral rival. Despite its relatively centrist reputation, the Congress Party, too, is pro-business, overseeing the liberalization of the Indian economy since the 1990s and ignoring the plight of the poor.