Lessons of the 1968 Tet Offensive

This Jan. 30, revolutionaries around the world marked the 50th anniversary of the Tet Offensive, a popular uprising backed by armed forces that changed the course of the U.S. war against Vietnam.

This Jan. 30, revolutionaries around the world marked the 50th anniversary of the Tet Offensive, a popular uprising backed by armed forces that changed the course of the U.S. war against Vietnam.

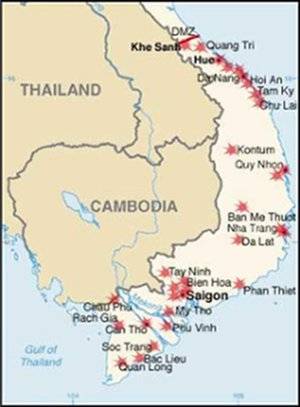

Totally surprising the U.S. government and the military command of its occupation army of more than a half-million U.S. troops, tens of thousands of fighters of the National Liberation Front of Vietnam (NLF), supported by an ample civilian network and by their fellow Vietnamese from the north, launched a powerful popular uprising in 140 cities and towns across Vietnam.

Many liberation fighters laid down their lives to free their country from the deadly U.S. occupation. But they made the Pentagon and the puppet Saigon army pay a heavy price. The offensive killed 500 U.S. soldiers each week from February into March and even more troops in the puppet army.

The Tet Offensive shook the U.S. establishment to its core. As March ended, President Lyndon Johnson announced that he would not seek another term. The top U.S. commander in Vietnam, Gen. William Westmoreland, who had promised his political and Wall Street masters that the end of the war was in sight, was sacked in June.

Among the objectives attacked were all four zonal headquarters of the puppet Saigon Army, eight out of eleven divisional headquarters and two U.S. army field headquarters. In Saigon, the capital of the south, NLF fighters attacked the U.S. Embassy, the Presidential Palace, the joint U.S.- Saigon armed forces headquarters and the South Vietnam naval headquarters.

The NLF liberated the ancient coastal city of Hue in the northern part of south Vietnam. They hoisted the NLF flag over the main tower there and freed some 2,000 prisoners. Before they retreated, they held the city for a month against a torrential rain of bombs and artillery that completely destroyed the city.

To the south, where the U.S. military used bombs, rockets and napalm on the town of Ben Tre, killing more than a thousand civilians, the commander told a reporter, “It became necessary to destroy the town in order to save it.” (New York Times, Feb. 8, 1968)

Much to their chagrin, from the hallways of the Pentagon to the halls of Congress to the mansions of the Wall Street masters of high finance, a large number of U.S. ruling-class figures realized the imperialist adventure in Vietnam was doomed to failure. And so did the people of the U.S.

The Tet Offensive galvanized the anti-war movement at home and opened the eyes of tens of thousands of GIs. Beginning in 1968 and growing in number each year through 1971, ordinary GIs might roll a live hand grenade into the tents of any officers or sergeants who were too zealous about sending their troops into battle.

What does this mean 50 years later? Of the many activists who protested Trump’s inauguration, who protested at both the 2017 and 2018 massive women’s marches, who shut down airports across the country to oppose Trump’s racist anti-Muslim policy, who faced off against the Klan and the Nazis in Charlottesville, Va., who toppled the Confederate statue in Durham, N.C. – many of their parents weren’t born by 1968.

Nevertheless, the explosive impact of the Tet Offensive has echoed through the years. It showed that a determined people, led by a thoroughly trained cadre of leaders steeped in years of anti-colonial struggle as well as Marxist-Leninist ideology, can defeat the most technically advanced military in history. As the Black Panthers said at that time, “The power of the people is greater than the man’s technology.”

That thought underlines the lesson of the Tet Offensive for activists today. By organizing and training ourselves in the art of struggle, by educating ourselves about the freedom fighters of the past and present, by communicating a clear message of solidarity with ongoing struggles erupting around the globe and here at home, we can defeat the warmakers and overturn this rotten system.