African Americans reject imperialism, part 2

Black Liberation and the Vietnamese struggle

One of the earliest developments in the Civil Rights Movement in the South related to Vietnam was a campaign by the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in the summer of 1965. A flyer and petition were circulated calling for African Americans to refuse induction into the military to fight in Vietnam since they were not given equal rights in the U.S.

By early January 1966, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee issued an official statement opposing the war and the draft. This intervention took place in the immediate aftermath of the racist murder of SNCC member Sammy Younge Jr. for his defiance of segregation laws in Alabama.

The SNCC statement read in part:

“The murder of Samuel Younge in Tuskegee, Ala., is no different than the murder of peasants in Vietnam. For both Younge and the Vietnamese sought and are seeking to secure the rights guaranteed them by law. In each case, the United States government bears a great part of the responsibility for these deaths. Samuel Younge was murdered because United States law is not being enforced. Vietnamese are murdered because the United States is pursuing an aggressive policy in violation of international law. The United States is no respecter of persons or law when such persons or laws run counter to its needs or desires.”

Julian Bond, a longtime SNCC organizer, ran successfully for the Georgia state legislature in late 1965. However, the authorities denied him the right to take his seat after he said publicly that SNCC’s position on Vietnam was his own as well.

In August 1966, the SNCC chapter in Atlanta embarked on a campaign to expose the racist character of the Vietnam War both domestically and in Southeast Asia. Women and men organizers in and around SNCC set up picket lines outside the induction center located near the heart of the African-American community.

These demonstrations soon prompted attacks by hostile mobs of whites along with police officers. Protesters were called racist slurs; had cigarettes, water and other objects thrown at them; and faced outright physical assaults.

1966 was the year there was a radical change in the character of SNCC’s leadership with the takeover by Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture) as chairman. Carmichael had direct organizing experience in Mississippi in 1964 and Alabama in 1965-66, where the Lowndes County Freedom Organization was formed and became known as the Black Panther Party.

There was an intensification of antiwar work and the linking of the African-American liberation struggle with global developments in Vietnam and other regions of Asia along with Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean and Latin America.

Black women oppose war on Vietnam

SNCC activists such as Diane Nash, a veteran of the Nashville Civil Rights Movement and the Freedom Rides of 1960-61, traveled to North Vietnam in 1966 to call for the end of U.S. aggression through addresses over Radio Hanoi.

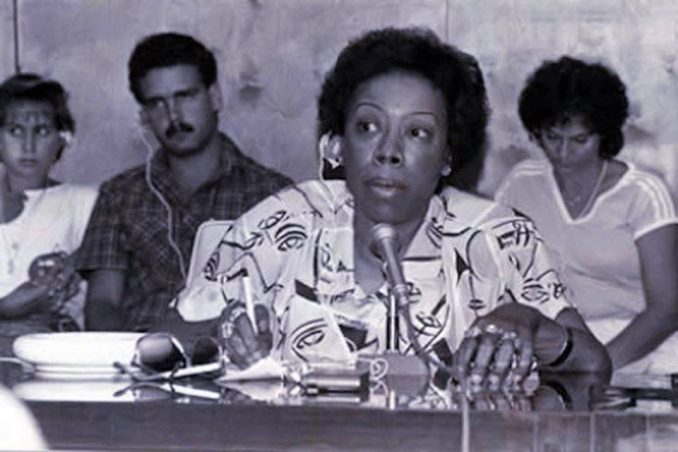

Gwen Patton, a graduate of Tuskegee University, was instrumental as well in organizing efforts to build the antiwar movement among African Americans.

In a report by Ashley Farmer on Patton’s contributions, she notes: “Patton constantly centered Black women within her pro-Black, anti-imperialist politics, making her a foundational figure in late 1960s Black feminist theorizing. Living and working alongside SNCC organizers like Faye Bellamy and Ethel Minor foregrounded the importance of developing emancipatory projects that were gender-inclusive. Patton was largely responsible for creating the Black Women’s Liberation Committee (BWLC), a women’s collective within SNCC. This group engaged in central questions about the ideological underpinnings of women, gender roles, and revolution.”

SNCC viewed the struggle for Black Liberation as part and parcel of the revolutionary movements sweeping Asia, Africa and other areas of the world. An International Section was created and directed by James Forman, the former executive secretary.

By 1967, Forman was presenting papers in national and international forums expressing solidarity with the Vietnamese and independence movements in Southern Africa, among other geopolitical areas.

By early 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was rapidly becoming outspoken about his opposition to the Vietnam War through newspaper columns, speeches, an antiwar march in Chicago in late March and the famous Riverside Church address, dubbed “Beyond Vietnam” on April 4, just one year to the date before his assassination in Memphis. On April 15, King spoke alongside Carmichael outside the United Nations in New York to thousands of anti-war opponents.

Heavyweight internationalists

Muhammad Ali, the heavyweight champion of the world, was one of the most widely known personalities internationally. Ali had changed his name from Cassius Clay when he went public with his conversion to the Nation of Islam after winning the championship in early 1964.

During this period in early 1964, Ali was close to Malcolm X, who left the NOI by late March. This caused an irreparable breach between the two men, with the heavyweight champion remaining with Elijah Muhammad.

By 1966, Ali was being hounded by the draft board. He officially refused induction in early 1967, citing religious grounds. Ali also emphasized that he did not feel obligated to wage war against the Vietnamese people based upon the lack of freedom for the Black man in the U.S.

Both Dr. King and SNCC supported Ali in his decision. This opened the way for broader alliances in opposition to the Vietnam War.

By May 1967, Stokely Carmichael had completed one year as chair of SNCC and turned over the leadership to H. Rap Brown (later known as Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin). He would later go to Cuba and address a summit of Latin American liberation organizations, attracting the attention of Premier Fidel Castro through his speech.

Carmichael also traveled to Hanoi and met with Ho Chi Minh. He subsequently reported that Ho encouraged him to focus more attention on the African Revolution. While in Hanoi, the former SNCC chairman requested a seminar on the building of a united front such as the NLF.

In recounting this event, Carmichael revealed that the U.S. began bombing Hanoi after the seminar started. Vietnamese party leaders then moved Carmichael into a bunker in order to continue the course. One bomb struck near the location of that session, causing some debris to fall on the instructor’s notes. Carmichael recounted how the dust was wiped away quickly and the class continued without interruption

“When I saw this I knew that the Americans would be defeated,” he jovially said. (Lecture delivered at Wayne State University in Detroit, March 13, 1992)

Next: The Black Panther Party, international solidarity and state repression.