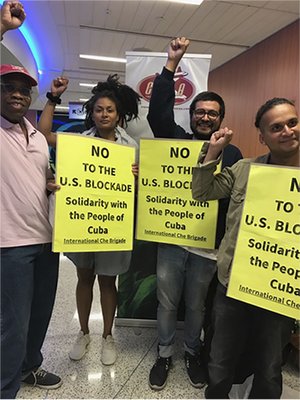

WWP brigadistas leave from Los Angeles International Airport.

On my second day visiting Cuba from the U.S. in October as a member of the “In the Footsteps of Che International Brigade,” I found myself suffering from a severe episode of back pain. I could not walk or put on my clothes, and I yelled out in excruciating pain. I also felt confused and worried about being in a foreign country with a different political system.

I started to think about my past experiences with back pain in the U.S., which include long waits to see a doctor in the Emergency Room and worrying about whether my insurance would approve treatment. I remembered facing discrimination in the U.S. as a person of color. I remembered being questioned whether I was an addict and being refused therapy or pain medication.

In Cuba the opposite situation occurred; I was treated with compassion and exemplary care. A security guard outside my room heard me yelling for help and immediately called for a doctor and nurse who both assisted me quickly. My stress was immediately eased as the doctor gently touched my shoulder and told me he would make me feel better, which calmed me in that moment.

The medical staff gently eased my suffering by giving me both a muscle relaxer and anti-inflammatory pill. I was then told to come back to the office in six hours, where I received a massage and an acupuncture treatment that continued to ease my suffering.

I was so appreciative and pleased by my experience that I was curious, so I asked one of the doctors why he chose to become a doctor. His response was that being a doctor in Cuba is not about economic gain but about the ability to help others in need. He said it was his calling in life, and his answer brought a huge smile to my face.

In Cuba, everyone has access to doctors, nurses, specialists and medications. There is a doctor-and-nurse team in every neighborhood in Cuba. If someone doesn’t like their neighborhood doctor, they can always choose another they are more comfortable with.

House calls are routine, in part because it’s the responsibility of the team to understand you and your health issues in the context of your family, home and neighborhood. This is key to the system that makes health care successful on the island. By catching diseases and health hazards early, the Cuban medical system can spend more time on prevention rather than treatment. This prevents epidemics and diseases from spreading through the island population.

When a health hazard like dengue fever or malaria is identified, there is a coordinated, nationwide effort to respond. Cubans no longer suffer from diphtheria, rubella, polio or measles. They have the lowest AIDS rate in the Americas and the highest rate of treatment and control of hypertension.

For health issues beyond the capacity of the neighborhood doctor, polyclinics provide specialists, outpatient operations, physical therapy, rehabilitation and labs. Those who need inpatient treatment can go to hospitals. The neighborhood medical team helps make the transition go smoothly for the patient.

Doctors at all levels are trained to administer acupuncture, herbal cures or other complementary practices that Cuban practitioners have found to be effective. Cuban researchers develop their own vaccinations and treatments when medications aren’t available, due to the U.S. blockade, or when they don’t exist.

I was quite pleased with what I experienced with the health care system in Cuba and how effective and humane it was. I wish one day for this system to be replicated in the U.S. so others can experience it.

Hamas issued the following statement on April 24, 2025, published on Resistance News Network. The…

By D. Musa Springer This statement is from Hood Communist editor and organizer D. Musa…

Portland, Oregon On April 12 — following protests in Seattle and elsewhere in support of…

This statement was recently issued by over 30 groups. On Friday, March 28, Dr. Helyeh…

When Donald Trump announced massive tariffs on foreign imports April 2, Wall Street investors saw…

The century-long struggle to abolish the death penalty in the U.S. has been making significant…