From the ‘July Days’ to the workers’ revolution in Russia 1917

At the end of the abortive workers and sailors’ uprising in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) in July 1917, nearly all the leaders of the Bolshevik Party were in prison or in hiding, slandered as agents of German imperialism. Yet within months the same Bolshevik party was poised to seize power for the working class.

At the end of the abortive workers and sailors’ uprising in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) in July 1917, nearly all the leaders of the Bolshevik Party were in prison or in hiding, slandered as agents of German imperialism. Yet within months the same Bolshevik party was poised to seize power for the working class.

These prisoners included the sailors Raskolnikov and his comrade Semyon Roshal from the hotbed of revolutionary fervor on the nearby island of Kronstadt, as well as Leon Trotsky and others from the national Bolshevik headquarters in the city center. Bolshevik leader V.I. Lenin and Grigory Zinoviev fled to Finland, where they stayed in hiding for fear of assassination. The Bolshevik headquarters was seized by the Provisional Government.

The Bolsheviks’ real crime, of course, was not that they served the German Kaiser, but that they stood with the revolutionary proletariat in Russia instead of abandoning it. The Bolsheviks did this during the “July Days,” when a large section — but still a minority — of the working class went into the streets against the Provisional Government. This provisional bourgeois regime continued to force the Russian Army to fight in World War I despite the hatred of the masses for that war.

Then came another turnaround that not only would lead to freeing the revolutionaries from prison, but also would put the Bolsheviks in a position to lead an insurrection.

Czarist general Lavr Kornilov, in a conspiracy with the leaders of the provisional government, that is, Prime Minister Alexander Kerensky and other pro-bourgeois forces, promised to lead troops against Petrograd to carry out a coup against the left forces. It soon became apparent that these counterrevolutionary officers intended not only to arrest and kill Bolsheviks, but also to eliminate the entire provisional government that issued from the revolution that overthrew the monarchy in February and March.

The only defense possible was one that depended on the masses, in particular the armed units of workers called the Red Guards. The parties in the government that feared a czarist counterrevolution absolutely needed the Bolsheviks to organize a defense because the revolutionary workers and sailors would follow orders only from the Bolsheviks. In return, the Bolsheviks would organize the defense of Petrograd only if the government freed their leaders and supplied them with arms for the workers.

Bolsheviks freed from prison

Faced with the danger from czarist reaction, the government allowed the local soviet, now led by Bolsheviks, to take leadership of the Military Revolutionary Committee to defend Petrograd. There was still a threat of czarist reaction, but the Kornilov uprising itself had already collapsed for the same reason that czarist forces were incapable of suppressing the earlier revolution: The rank-and-file troops would not follow the orders of the czarist officers.

Without troops to do the fighting, most of the officers that Kornilov had recruited found excuses to stay away from battle.

In his book, “Kronstadt and Petrograd in 1917,” Fyodor Raskolnikov gives an example of how this happened with the “so-called ‘Savage Division,’ a cavalry division of volunteers from the (mainly Muslim) peoples of the Caucasus, who were exempt from conscription. The Bolshevik Party mobilized a delegation of Muslim notables who visited the advancing troops and explained that they had been misled as to the real situation in Petrograd.”

As happened so often in those days, all it took was contact with the revolutionary workers of Petrograd to convince the troops to turn the guns around on their officers.

By mid-October the Bolsheviks were a majority of the Petrograd Soviet and directed the Military Revolutionary Committee. The revolt of the troops against the Czar during the earlier “February Revolution” had been mostly spontaneous, with the troops changing consciousness as a result of contact with the striking workers of Petrograd, many of them women.

Using the freer access to the soldiers they won in this revolution, the Bolsheviks carried on agitation and organization of the troops not only in Petrograd but also at the front. Troops formed their own organization, electing representatives to the Soviet of Workers and Soldiers, effectively breaking the chain of command.

Meanwhile the sailors of Kronstadt and the Baltic Fleet were solidly with the revolution. On some ships hundreds of sailors had joined the Bolsheviks and were urging the soviets to take power in the name of the working class.

The soldiers too were determined not to keep fighting the war against Germany. In his detailed memoir, “The Russian Revolution of 1917: a Personal Record,” the left-Menshevik N. N. Sukhanov wrote how representatives of regiments came in one by one to tell the Military Revolutionary Committee that they did not trust the Kerensky government and would rise up at the first call to overthrow it.

By Oct. 21 (Nov. 3 according to the Western calendar), this included the Petrograd garrison, with its hundreds of thousands of soldiers. Petrograd and Russia were moving inexorably toward a second revolution.

Troops change sides

Then a new crisis came up in the Petrograd Soviet. The army commandant of the Peter-Paul Fortress, most likely a pro-czarist officer, refused to recognize the commissar assigned to the fortress from the Military Revolutionary Committee and threatened him with arrest. This strategically important fortress inside Petrograd was essential to the victory of the planned uprising. But to attempt to take it by force was risky, an act of war. Sukhanov wrote:

“Trotsky had another proposal, namely, that he, Trotsky, go to the Fortress, hold a meeting there, and capture not the body but the spirit of the garrison. … Trotsky set off at once, together with Lashevich. Their harangues were enthusiastically received. The garrison, almost unanimously, passed a resolution about the Soviet regime and its own readiness to rise up, weapons in hand, against the bourgeois government. … A hundred thousand extra rifles were in the hands of the Bolsheviks.”

The national Congress of Soviets had been set for Oct. 25 (Nov. 7) in Petrograd. It would be a perfect time for this body to deliberate about taking state power. But the Provisional Government could still surround the congress with reactionary troops and arrest the Soviet.

The Bolshevik leaders considered it more prudent to move first. No street clashes were necessary. All the street fighting had already happened in February (March). And it was no secret coup. The mainly Bolshevik leaders of the Military Revolutionary Committee openly declared their intention to protect the Congress of Soviets.

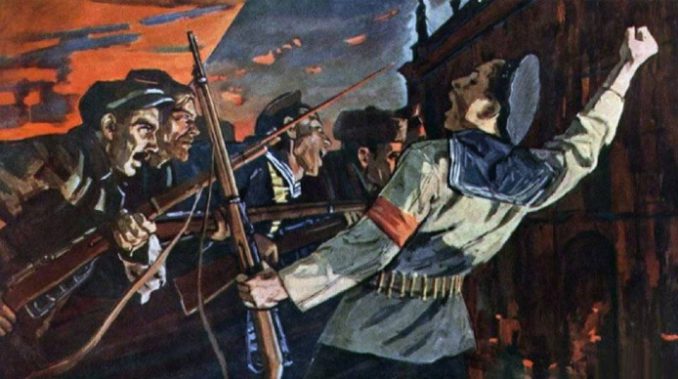

The sailors of the Baltic Fleet, the workers who controlled the bridges, the Petrograd garrison, the soldiers at the Peter-Paul Fortress — all had already joined the revolution. Under orders of the Soviet’s Military Revolutionary Committee on the night of October 24-25 (November 6-7), armed workers known as Red Guards and revolutionary sailors seized postal and telegraph offices, electric works, railroad stations and the state bank.

That night at 9:45 p.m. a blank cannon shot rang out from the Cruiser Aurora, whose sailors were loyal to the Bolsheviks, anchored nearby in the Neva River. At this signal, thousands of sailors and Red Guards stormed the Winter Palace. The Provisional Government collapsed.

Exhausted workers, soldiers and Bolshevik leaders crowded the Congress of Soviets that had been scheduled for Oct. 25 (Nov. 7). After word came that the Winter Palace was taken, people rose, filling the hall with shouts and cheers. Lenin came to the podium and proclaimed, “We shall now proceed to construct the socialist order.”

This was just the beginning. To sign a peace with Germany took months. There followed a long struggle and civil war before the Soviet Union could even be established. The Baltic Fleet sailors and armed workers of Petrograd became the shock troops of the Red Army, and many of these heroes, who were the driving force of the Russian Revolution, lost their lives in the costly civil war and invasion by Japan, Czechoslovakia, Britain, France, the United States and other capitalist countries that lasted until 1922.

Nevertheless, the experience of 1917 in Russia showed that the interaction between the revolutionary workers and the soldiers of the Petrograd garrison as well as the decisive actions of the sailors of the Baltic Fleet made the success of the revolution possible.

Adapted from a chapter of “Turn the Guns Around: Mutinies, Soldier Revolts and Revolutions” by John Catalinotto.