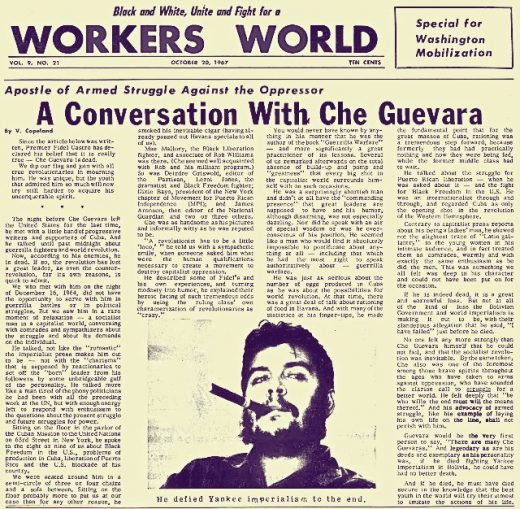

A conversation with Che Guevara

Apostle of armed struggle against the oppressor

Workers World, Vol. 9, No. 21, October 20, 1967

Workers World, Vol. 9, No. 21, October 20, 1967

Since the article below was written, Premier Fidel Castro has declared his belief that it is really true – Che Guevara is dead.

We dip our flag and join with all true revolutionaries in mourning him. He was unique, but the youth that admired him so much will now try still harder to acquire his unconquerable spirit.

* * *

The night before Che Guevara left the United States for the last time, he met with a little band of progressive writers and supporters of Cuba. And he talked until past midnight about guerrilla fighters and the world revolution.

Now, according to his enemies, he is dead. If so, the revolution has lost a great leader, as even the counter-revolution, for its own reasons, is quick to admit.

We who met with him on the night of December 16, 1964, did not have the opportunity to serve with him in guerrilla battles or in political struggles. But we saw him in a rare moment of relaxation – a socialist man in a capitalist world, conversing with comrades and sympathizers about the struggle and about its demands on the individual.

He talked, not like the “romantic” the imperialist press makes him out to be – not with the “charisma” that is supposed by reactionaries to set off the “born” leader from his followers by some unbridgeable gulf of the personality. He talked more like a man tired of the phony politicians he had been with all the preceding week at the UN, but with enough enthusiasm to the questions about the present struggle and future struggles for power.

Sitting on the floor in the parlor of the Cuban Mission to the United Nations on 63rd Street in New York, he spoke to the eight or nine of us about Black Freedom in the U.S., problems of production in Cuba, liberation of Puerto Rico and the U.S. blockade of his country.

We were seated around him in a semi-circle of three or four chairs and a sofa between. Sitting on the floor probably more to put us at our ease than for any other reason, he smoked his inevitable cigar (having already passed out Havana specials to all of us).

Mae Mallory, the Black Liberation fighter and associate of Rob Williams, was there. So was Deirdre Griswold, editor of the Partisan, Leroi Jones, the dramatist and Black Freedom fighter; Dixie Bayo, president of the New York Chapter of Movement for Puerto Rican Independence (MPI); and James Aronsen, then editor of the National Guardian and two or three others.

Che was as handsome as his pictures and informally witty as he was reputed to be.

“A revolutionist has to be a little ‘loco,’” he told us with a sympathetic smile, when someone asked him what were the human qualifications necessary to create a movement to destroy capitalist oppression.

He described some of Fidel’s and his own experiences, and turning modesty into humor, he explained their heroic facing of such tremendous odds by using the ruling class’ own characterization of revolutionaries as “crazy.”

You would never have known by anything in his manner that he was the author of the book “Guerrilla Warfare” – and more significantly a great practitioner of its lessons. Several of us remarked afterwards on the total absence of build-up and pomp and “greatness” that every big shot in the capitalist world surrounds himself with on such occasions.

He was a surprisingly shortish man and didn’t at all have the “commanding presence” that great leaders are supposed to have, and his humor, although disarming, was not especially dazzling. Nor did he speak with an air of special wisdom or was he over-conscious of his position. He seemed like a man who would find it absolutely impossible to pontificate about anything at all – including that which had the most right to speak authoritatively about – guerrilla warfare.

He was just as serious about the number of eggs produced in Cuba as he was about the possibilities for world revolution. At that time, there was a great deal of talk about rationing of food in Havana. And with many of the statistics at his finger-tips, he made the fundamental point that for the great masses of Cuba, rationing was a tremendous step forward, because formerly they had had practically nothing and now were being fed, while the former middle class had to wait.

He talked about the struggle for Puerto Rican liberation – when he was asked about it – and the fight for Black Freedom in the U.S. He was an internationalist through and through, and regarded Cuba as only the opening shot in the revolution of the Western Hemisphere.

Contrary to capitalist press reports about his being a ladies’ man, he showed not the slightest trace of “Latin gallantry” to the young women in the audience, and in fact treated them as comrades, warmly and with exactly the same enthusiasm as he did the men. This was something we all felt was deep in his character and could not have been put on for the occasion.

If his is indeed dead, it is a great and sorrowful loss. But not at all of the kind of loss the Bolivian Government and world imperialism is making it out to be, with their slanderous allegation that he said, “I have failed,” just before he died.

No one felt any more strongly than Che Guevara himself that he could not fail, and that the socialist revolution was inevitable. By the same token, Che also was one of the foremost among those brave spirits throughout the ages who have taken to arms against oppression, who have sounded the clarion call to struggle for a better world. He felt deeply that “he who wills the end must will the means thereof.” And his advocacy of armed struggle, like his example of laying his own life on the line, shall not perish will him.

Guevara would be the very first person to say, “There are many Che Guevaras.” And legendary as are his deeds and exemplary as his personality was, if he died fighting Yankee imperialism in Bolivia, he could have had no better death.

And if he died, he must have died secure in the knowledge that the best youth in the world will try their utmost to imitate the actions of his life.