East Harlem residents say, ‘Remove the racist Sims’ statue!’

Sims performed hundreds of surgeries on enslaved women without anesthesia, antiseptics or their consent.

The struggle is growing for the removal of racist Dr. James Marion Sims’ statue from New York City’s Central Park. Sims, known as the “father of gynecology,” made alleged medical advances through his cruel practice of performing unethical, gynecological surgical techniques on enslaved Black women without anesthesia, antiseptics or their consent. In his quest for fame, he manipulated the institution of slavery to perform his brutal experiments.

The national movement to get rid of Confederate monuments following recent white supremacist violence in Charlottesville, Va., led local activists to renew their push to take Sims’ statue down.

Black Youth Project 100 held a protest Aug. 19 in front of the monument, located at 103rd Street and Fifth Avenue in East Harlem, to demand its removal. Other organizations have demonstrated, too. Boldly, someone spray-painted “racist” on the statue on Aug. 26.

NYC City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito, who has been involved in this campaign since 2011, called for the statue to come down at an Aug. 21 press conference, calling Sims’ “despicable acts … repugnant and reprehensible.” (Daily News, Aug. 21)

East Harlem residents have campaigned for years to get this affront to their community taken down. A recent poll of that community showed an overwhelming number support the statue’s removal.

Medical experimentation = torture

Also addressing this issue post-Charlottesville was Steve Benjamin, African- American mayor of Columbia, S.C., who said that Sims’ offensive statute on their Statehouse grounds “should come down. … [He] tortured slave women and children for years as he developed his treatments for gynecology.” (MSNBC, Aug. 15)

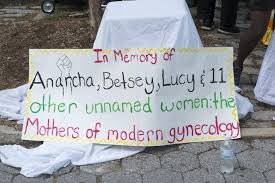

“Slaveowner” Sims carried out these surgeries in the U.S. South from 1845 to 1849 with no training in gynecology. In Alabama, he performed hundreds of surgeries on enslaved women that he “owned” or “borrowed.” He experimented many times on 12 enslaved women, an astounding 30 times on one of them. Many women died.

Plantation owners took enslaved women to Sims for treatment so they could continue working and would produce more children to add to the enslaved population. Enslaved people had no personal rights and were the property of their “owners” who held possession of their lives, bodies and labor. Sims also experimented on enslaved Black men.

Sims’ copious notes revealed slaveowner language, sprinkled with racial slurs and vivid depictions of Black women’s bodies. Later, after “successful” experimentation, he used the same surgical procedures on white women in New York, but used anesthesia for them.

A common, outrageous racist belief then was that Black people were insensitive to pain — and thus didn’t need anesthesia during surgery. This sheds light on the historically violent oppression of Blacks in the U.S., and was a horrifying testament to the brutality of slavery and its relationship to U.S. medicine. It highlights the intersection of race and medicine.

Harriet Washington writes about this extensively and Sims’ crimes, in her groundbreaking book, “Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present.” (Doubleday, 2007)

Neonatal tetanus in newborns, acquired through infection of the unhealed umbilical cord, often cut with a nonsterile instrument, afflicted many enslaved children. It is now known to result from the impoverished conditions of enslaved peoples’ living quarters.

But the archracist Sims attributed neonatal tetanus to enslaved Africans’ “inferiority.” So this “medical monster” performed horrific surgeries on enslaved women’s babies without anesthesia. All of these babies died. He blamed the fatalities on “the ignorance” of their mothers and midwives, while his crimes caused these deaths.

Even as he was committing these crimes, Sims founded the Woman’s Hospital of New York in 1855, where he performed operations on indigent women who then had lengthy hospital stays and underwent repeated procedures. Despite his record of killing women and children and inflicting pain, he was named president of the American Medical Association in 1875 and then president of the Gynecological Society in 1879.

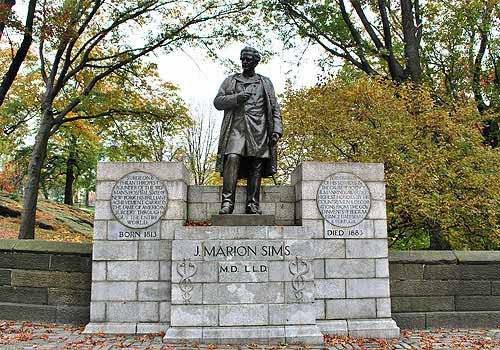

The 13-foot statue of Sims was installed at its present location in 1934 — in East Harlem’s historically African-American and Puerto Rican neighborhood. In an insult to oppressed women, the wording below it reads: “Surgeon and Philanthropist, Founder of the Woman’s Hospital State of New York. In recognition of his services in the cause of science and mankind.” Wording on the base adds: “His brilliant achievement carried the fame of American surgery throughout the entire world.”

The current struggle is over whether the city should keep, remove or relocate the statue. The East Harlem Preservation organization began its campaign in 2007 in solidarity with efforts by activist Viola Plummer, member of the December 12th Movement, to call attention to Sims’ cruel experiments. That year, NYC Councilmember Charles Barron petitioned the NYC Parks and Recreation Department to remove the statue. Proposals have been raised to instead honor the women Sims tortured.

The EHP reports that then-East Harlem Councilmember Mark-Viverito appealed to the Parks Department in 2011 to remove the statute because it is a “constant reminder of the historic cruelty endured by women of color” — and in a community comprised mainly of people of color.

The Parks Department refused to honor these requests, claiming “the city does not remove ‘art’ for content.” In 2016, Community Board 11 called for the statue’s removal. That year, at a speakout at Sims’ statue “community members honored their ancestors and condemned the memorial to assaults on Black and Latina female bodies,” said the EHP. In February, EHP addressed this issue in a cable TV panel discussion, which included author Harriet Washington. The organization is working to gain more endorsements to pressure the Parks Department to remove this racist’s monument.

EHP declares that “Sims is not our hero” and maintains that the statue’s presence is an insult to the “neighborhood’s majority Black and Puerto Rican residents — two groups that have been subjected to medical experiments without permission or regard for their wellbeing.” Moreover, there are many heroic “Black and Puerto Rican women and men who have made great medical and scientific contributions” to the community. Our children, says the EHP, should learn about them — and know their lives matter.

Sims’ statues, like Confederate monuments, memorialize white supremacist slaveowners and murderers. They perpetuate the view that this “medical monster” was the “father of gynecology,” a benevolent man of science, rather than a sadistic racist whose inventions were brutally enabled by slavery.