Big Pharma prices soar, Part 2

Abundant gov’t investigations, but no end to crisis

Lifesaving medications, including Harvoni which can cure hepatitis C, are often developed through taxpayer-funded research. But they are priced out of reach for most of the people who need them. There are no laws or other restrictions to stop pharmaceutical companies from charging whatever they can get away with. And they count on Medicaid and Medicare to pick up the bill.

Lifesaving medications, including Harvoni which can cure hepatitis C, are often developed through taxpayer-funded research. But they are priced out of reach for most of the people who need them. There are no laws or other restrictions to stop pharmaceutical companies from charging whatever they can get away with. And they count on Medicaid and Medicare to pick up the bill.

While the December 2016 findings of the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging should clearly be grounds to indict the CEOs of pharmaceutical companies responsible for price gouging, the odds are against this ever happening. (For names of offending companies, see Part 1 in Jan. 5 WW.)

Since 1959 the U.S. Congress has held over 50 separate hearings to investigate the pharmaceutical industry. All have reached pretty much the same conclusion: Pharmaceutical companies are maximizing their profits at the expense of the public.

Despite all these hearings, at who knows what cost, Congress has yet to pass any legislation that would restrict pharmaceutical companies from charging whatever they want. Nonetheless, the hearings go on and on.

In 2014 the Senate Subcommittee on Primary Health and Aging held a hearing to investigate steep and unexpected price hikes on some generic drugs. But the cost of many generic drugs has continued to skyrocket.

In 2015 the U.S. Congress held hearings to investigate Gilead Sciences for raising the cost of drugs, including Harvoni. The investigation concluded that the only explanation for the high costs was the company’s greed: Gilead was charging as much as it could get away with for the drug because it could.

Early in 2016 the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform called Mylan CEO Heather Bresch to testify after the outrageous rise in the price of the lifesaving EpiPen. While Mylan has now lowered the cost, it still remains significantly higher than what is charged outside the U.S.

In December 2016, the U.S. Justice Department brought criminal charges against two pharmaceutical executives for conspiring with other drug makers to fix generic drug prices. The DOJ charged former pharmaceutical executives Jeffrey A. Glazer and Jason T. Malek with colluding over the course of seven years with “unnamed brand-name corporations and individuals” to fix prices and rig bids on drugs used to treat bacterial infections, acne and diabetes.

Six pharmaceutical companies are currently under investigation for conspiring to fix prices of generic medicines under a civil action filed by 20 states. News of these investigations sent pharmaceutical stocks tumbling, but odds are it’s a temporary setback.

U.S. gov’t policies promote higher drug prices

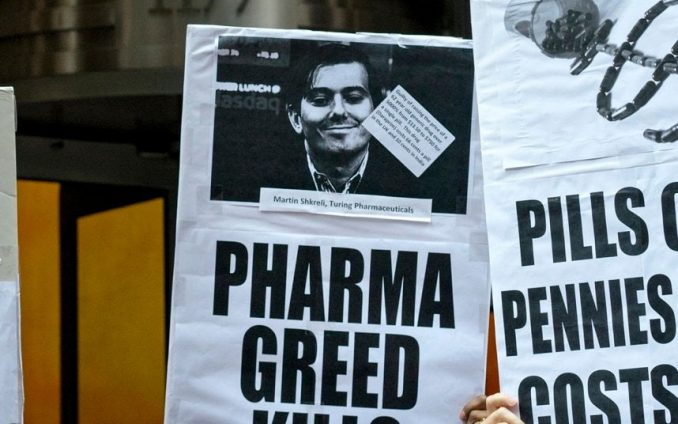

When the House Committee on Oversight and Government attempted to question Martin Shkreli in 2015 over the dramatic price increase of Daraprim, he refused to answer any questions other than explaining how to pronounce his name. After repeatedly taking the Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination, Shkreli later expressed his disdain for the process in a Twitter post: “Hard to accept that these imbeciles represent the people in our government.”

While his contempt of Congress comes from the point of view of people in the billionaire class that Congress actually protects, in a way Shkreli underscored an important problem: The U.S. remains the only developed country with no real oversight to restrict what drug companies can charge the public.

Prescription drugs can be found at lower prices — outside the U.S. In Egypt Harvoni costs $10 per pill. Daraprim can still be purchased in Britain for 66 cents a pill and costs even less in India. An EpiPen two-pack can be purchased at a pharmacy in Canada for $145 and in Britain for $69. If you didn’t live in the U.S., you could buy all these drugs and more from other countries for far less.

However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration makes it very difficult for individuals to import prescription drugs for personal use unless the drug is for a serious condition and not available in the U.S. Even then, no more than a three-month supply can be imported.

Congress passed the Prescription Drug Marketing Act (PDMA) in 1987 prohibiting anyone other than U.S. pharmaceutical manufacturers from importing prescription drugs. Some states have recently required doctors to electronically send prescriptions to pharmacies instead of giving written prescriptions to patients, making it harder for them to seek lower prices.

Profits before people remains the governing principle that dictates U.S. policies. The U.S. is the only country that allows pharmaceutical manufacturers to set drug prices with no limitations.

As of this writing, one of two people being vetted as the next Food and Drug Administration commissioner is Jim O’Neill, a managing director at Mithril Capital Management, run by one of Donald Trump’s billionaire donors and advisors. O’Neill has suggested that the FDA let drug companies put products on the market before proving they work. They just have to be “safe” before being sold. O’Neill’s take on new drugs: “Let’s prove efficacy after they’ve been legalized.”

This is after passage of the 21st Century Cures Act under the Obama administration, which has already undermined patient safety by requiring less restrictive testing before drugs are marketed.

Whether Trump appoints O’Neill or another billionaire, it’s clear that the end game won’t be to improve conditions for working and poor people. Untested and potentially unsafe new drugs are not the solution to the health crisis caused by exorbitant prices. The prescription called for is to eliminate the capitalist profit drive behind this crucial industry.