Prisoners hold first nationally coordinated work stoppage

Prison inmates around the country launched the first nationally coordinated work stoppage on Sept. 9. In their own words, these heroic inmates have gone on strike “not only [to] demand the end to prison slavery, [but to] end it ourselves by ceasing to be slaves.” (iwoc.noblogs.org, April 1)

In facilities across the country, inmates, who are disproportionately Black, Latinx or Indigenous, are forced to labor for only a fraction of the legal minimum wage. In many state facilities, prisoners are not paid at all for their labor.

The superprofits generated by this slave labor have fueled the mass incarceration epidemic, prolonging the imprisonment and enslavement of millions.

Despite a near total suppression of the story by the corporate media, the strike spread to at least 46 state and federal prisons. The actual number of affected prisons is likely much higher, as this number only reflects reports received from inmates who are able to send out updates amidst prison repression.

Prison officials in at least 31 facilities instituted total lockdowns in apparent retaliation for the strike. Based on the inmate populations of these 31 locked-down facilities, no fewer than 57,000 incarcerated workers withheld labor or were otherwise prevented from working due to the strike. (iwoc.noblogs.org, Sept. 14)

An inmate at Alabama’s Holman Correctional Facility relayed this message: “12:01 Sept 9th, all inmates at Holman Prison refused to report to their prison jobs without incident. With the rising of the sun came an eerie silence as the men at Holman laid on their racks reading or sleeping. Officers are performing all tasks.” (supportprisonerresistance.noblogs.org, Sept. 9)

Florida prisons join strike

Inmates in at least five Florida prisons joined the strike. (miamiherald.com, Sept. 13) More than 400 inmates at Holmes Correctional Facility participated in a righteous uprising Sept. 7, briefly taking control of the prison.

According to a guard at Holmes, “[Prison guards] would get one dorm under control and then it would start in another dorm. It was every dorm, as if it was planned.” (miamiherald.com, Sept. 8) By Sept. 9, inmates had begun a series of sit-ins, refusing to perform any labor for the prison. (chipleypaper.com, Sept. 9)

According to an anonymous source at Washington (state) Corrections Center for Women, at least three inmates refused to report for work at the prison library on Sept. 9. For this they were each sentenced to 20 days in solitary confinement. (supportprisonerresistance.noblogs.org, Sept. 21)

When a group of inmates at South Carolina’s maximum security Perry Correctional Institution refused to return to their cells Sept. 9, guards initiated a total lockdown, confining approximately 1,000 prisoners to their cells throughout the weekend and preventing any inmate labor from being performed. (wyff4.com, Sept. 12)

An anonymous report from a prisoner inside South Carolina’s Broad River Correctional Facility described the guards’ retaliation against strikers: “Prison pigs here at Broad RV Corr, hit us with everything they got after we exposed these inhumane living conditions. They even bought and came through with new phone detectors. These pigs telling us if we do it again, report anything, we will be searched and locked down for longer periods. Does this not place you in the mind the time when slaves were punished for learning to read or write?” (facebook.com/BlkJailhouselawyer, Sept. 22)

Due to the mainstream media whiteout, heightened repression by prison guards and the refusal of prison staff to respond to independent media inquiries, it is impossible to determine the full extent of the strike. But based on what little information is available, it is clear that the Sept. 9 strike has been the largest coordinated prisoner action ever to take place in the United States.

Whether the strike continues to spread or whether business as usual is temporarily restored in the prison system, it is undeniable that the solidarity in action both within and outside the prisons has propelled the movement forward by leaps and bounds.

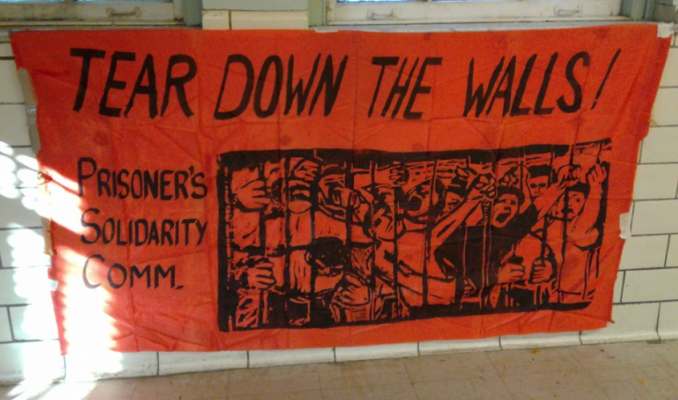

Organizers and people of conscience on the outside can help further advance the struggle by writing letters to inmates and forming prison solidarity networks among communities most affected by mass incarceration.