THE 1971 ATTICA REBELLION: George Jackson & the revolutionary prison movement of 2016

From a talk at a Workers World Party campaign meeting held on Sept. 10 in Detroit. Other speakers included Carlos Topp of the Moratorium NOW! Coalition, Joe Mchahwar of Fight Imperialism Stand Together (FIST), Yvonne Jones of the Detroit Active and Retired Employees Association and WWPpresidential candidate Monica Moorehead. Debbie Johnson of WWP’s Detroit branch chaired the meeting.

In looking at the heroic seizure of Attica Prison on Sept. 9, 1971, we must acknowledge the real purpose of the prison system in the United States. The millions who remain incarcerated, paroled and supervised by the so-called correctional institutions are there not for the purpose of rehabilitation. Prisons are a mechanism to facilitate the continuing national oppression, superexploitation and social containment of peoples of African and Latin American descent, who are considered the most dangerous subjects of the U.S. capitalist and imperialist system.

Those who took over Attica Prison recognized that their existence inside the walls was part and parcel of a broader system of racism, which extended back to the days of the Atlantic slave trade in North America and the entire Western Hemisphere. These men who rebelled during those fateful five days did so in response to the overall struggle for national liberation being waged on the outside.

By 1971, the African-American movement against racism, national oppression and capitalist exploitation had reached an apex. For the previous 16 years, the African people had developed tactics from the collective boycott to the sit-in, mass demonstrations, bloc voting, self-organization, urban rebellion and the armed revolutionary seizure of power.

One cannot understand the Attica Rebellion without examining the ongoing struggle of the African-American people and its connection to the independence movements of African people throughout the globe.

After the national independence of the Gold Coast (renamed Ghana) in 1957, a model of self-government, social reconstruction and the development of a Pan-African foreign policy would guide the most advanced elements within the oppressed nation.

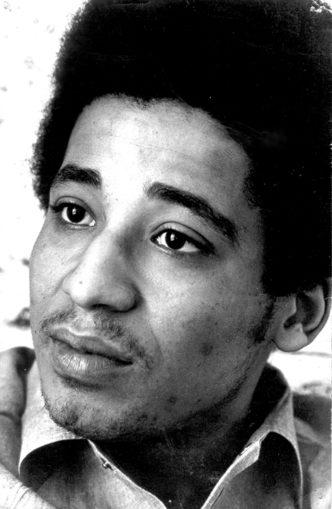

George Jackson, Jonathan Jackson and the Attica Rebellion

At the same time, we cannot fully grasp the mood of the African-American inmates at Attica without reviewing the theoretical and literary contributions of George L. Jackson. Through his two books of prison writings, “Soledad Brother” and “Blood in My Eye,” Jackson reveals the social plight of the African American during this period.

Incarcerated in 1960 in connection with the robbery of a filling station for the total amount of $70, Jackson was given a one-year-to-life sentence. In other words, the system will either keep you imprisoned for life or release you when they think you are fully broken as a human being. His imprisonment paralleled the burgeoning African-American liberation movement of the period.

It was during February of 1960 that the sit-in movement began in full swing. Sit-ins had occurred as early as 1958 in Wichita, Kansas, and Austin, Texas. Nonetheless, it was in Greensboro, N.C., where four students from the local agricultural and technical university would ignite a fire that burned for more than a decade.

Out of these protests emerged the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which prompted the formation of other organizations such as the Revolutionary Action Movement, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, the Black Panther Party, the Republic of New Africa and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, among others.

All of these organizations and their theoretical works had a tremendous impact on the imprisoned population. A former friend of mine who was incarcerated during the late 1960s in Ohio told me during the early 1980s what the atmosphere was like behind bars. He said that the African-American inmates were observing what was happening on the outside with the struggle for Civil Rights, the urban rebellions and the growth of revolutionary organizations. He said they were frustrated by being locked up and the situation grew so tense that it exploded. Although the rebellion was crushed by the guards, he reflected on the fact that it was a “liberating experience.”

Jonathan Jackson, the 17-year-old brother of George, was active in the movement to free the Soledad Brothers. These three activist prisoners — George Jackson, Fleeta Drumgo and John Clutchette — were charged with the killing of a white prison guard in January 1970. The action was supposedly carried out in retaliation for the murder of three African-American prisoners including W.L. Nolen, a leader among revolutionary prisoners who was gunned down by a guard shooting from a tower 30 feet above.

The younger Jackson took it upon himself in spontaneous coalition with three inmates, Ruchell Magee, William Christmas and James McClain, to take a judge, prosecutor and three jurors in captivity in a failed bid to free the Soledad Brothers on August 7, 1970, at the Marin County Courthouse. Jonathan, Christmas and McClain were killed, along with the white judge. Ruchell Magee survived but remains imprisoned up until today, having been incarcerated for some 53 years.

Six years ago during a Black August forum at this office I noted that: “Jackson became politicized in prison like so many other African-American men from Malcolm X to Eldridge Cleaver. Jackson was the co-founder, along with W.L. Nolen, of the Black Guerrilla Family in prison. He would later join the Black Panther Party and was appointed field marshal.

“In 1970, Jackson wrote of the slave system and its antecedents in the United States: ‘After the Civil War, the form of slavery changed from chattel to economic slavery, and we were thrown onto the labor market to compete at a disadvantage with poor whites.’ (‘Soledad Brother,’ 1971, p. 175)

“Jackson continued: ‘Ever since that time, our principal enemy must be isolated and identified as capitalism. The slaver was and is the factory owner, the businessman of capitalist Amerika, the man responsible for employment, wages, prices, control of the nation’s institutions and culture. It was the capitalist infrastructure of Europe and the U.S. which was responsible for the rape of Africa and Asia.’

“Therefore, Jackson saw clearly that there was a logical progression from the system of chattel slavery to industrial capitalism. He defines the struggle as one of both national oppression and class exploitation, but that the class struggle is the primary struggle.”

This same presentation continued, emphasizing that “Jackson notes ‘Capitalism murdered those 30 million in the Congo. Believe me, the European and Anglo-Amerikan capitalism would never have wasted the ball and powder were it not for the profit principle. The men, all the men who went into Africa and Asia, the fleas who climbed on that elephant’s back with rape on their minds, richly deserve all that they are called. Every one of them deserved to die for their crimes. So do the ones who are still in Vietnam, Angola, and the Union of South Africa (USA!!).’”

I later said: “Nonetheless, Jackson emphasizes the need for an objective view of the enemy and the tactics needed to defeat capitalism and imperialism. It will require a scientific analysis of the problems facing the oppressed and a people’s organization to defeat it.

“Jackson goes on to say: ‘We must not allow the emotional aspects of these issues, the scum at the surface, to obstruct our view of the big picture, the whole rotten hunk. It was capitalism that armed the ships, free enterprise that launched them, private ownership of property that fed the troops. Imperialism took up where the slave trade left off.

“‘It wasn’t until after the slave trade ended that Amerika, England, France, and the Netherlands invaded and settled in on Afro-Asian soil in earnest. As the European industrial revolution took hold, new economic attractions replaced the older ones; chattel slavery was replaced by neo-slavery. Capitalism, “free enterprise,” private ownership of public property armed and launched the ships and fed the troops; it should be clear that it was the profit motive that kept them there.’” (“Soledad Brother,” p. 176)

George Jackson’s legacy and Attica today

A prison movement continues into the modern period with the advent of hunger strikes and other forms of resistance. This was brought to the attention of the U.S. and the world by the recent events at Pelican Bay and other facilities in Georgia, Ohio and Michigan.

The plight of the Rev. Edward Pinkney is an illustration of the continuing racist character of the legal system. Convicted without evidence, Pinkney was targeted for his outspoken opposition to racism in Berrien County, Mich. He has recently been transferred from the dreaded Marquette Branch Prison in the Upper Peninsula to a facility in Muskegon. We have been waging a campaign for his exoneration and release for over two years.

Since the early 1970s, the rate of incarceration in the U.S. has grown by over 500 percent. Disproportionately, the African and Latinx people are imprisoned in the hellholes and dungeons of the capitalist system. There are an estimated 2.2 million people incarcerated in the U.S., the highest per capita rate of imprisonment in the world by a society that claims to be the citadel of democracy and human rights.

Although the Attica Rebellion was brutally crushed at the aegis of the billionaire and then Republican governor, Nelson Rockefeller, resulting in the deaths of over 40 people — including several guards held hostage by the inmates — the movement continues for prisoners’ rights, to free political prisoners and for the abolition of the system of incarceration.

We can never be free as long as these institutions exist. The abolition of prisons will coincide with the total liberation of the African-American people and the destruction of the world capitalist and imperialist system. This struggle cannot be divorced from the broader movement to eliminate racism and national oppression.