Black farmers still seek justice

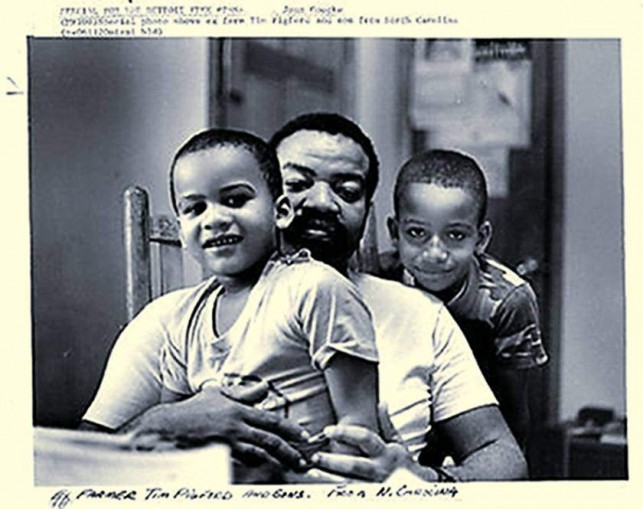

Black farmers in the South filed a federal class action lawsuit known as Pigford vs Glickman in 1997. Timothy Pigford was a Black farmer; Dan Glickman was the U.S. secretary of agriculture. The lawsuit alleged racial discrimination by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in allocating loans, disaster payments and assistance.

The lawsuit covered a 16-year period during which African Americans applied for farm credit or program benefits. Plaintiffs said they were prevented from applying for loans, denied loans or given loans with unfair terms; they claimed this treatment of their loan applications led to economic damage. They also said the agency failed to process racial discrimination complaints.

USDA farm programs were set up in the 1930s. From the beginning, Black farmers faced discrimination. During the 1960s, 1980s and 1990s, USDA staff denied loans in retaliation for their Civil Rights activism and refused to assist with their agricultural needs and concerns.

The farmers won their historic case in 1999. District Judge Paul L. Friedman issued a consent decree in the class action lawsuit which covered African-American farmers who farmed or attempted to farm between 1981 and 1996, applied for farm credit and program benefits, and filed a complaint against the USDA by July 1997.

In July 2007, Congress member John Conyers introduced H.R. 3073, which provided a way to determine the merits of claimants who met the class criteria in the Pigford lawsuit against USDA racial discrimination but were denied compensation. The Pigford Claims Remedy Act of 2007 budgeted $100 million for these farmers; it was absorbed into the 2008 Farm Bill. Then another $1.15 billion was allocated by Congress in December 2010 in the Claims Resolution Act.

In 2011, Judge Friedman approved financial compensation to late-filers in the “Pigford II” case; however, there were strict guidelines. Each claim had to be submitted by a deadline, reviewed and approved.

Funds began to be disbursed in the fall of 2013, with plaintiffs each receiving a $50,000 cash reward and $12,500 in an IRS account to pay related taxes. Because the settlement took decades to resolve, many farmers died waiting for justice. Of the 18,000 claims approved, 4,000 to 5,000 are estate claims.

‘A bittersweet victory’

National Black Farmers Association President John Boyd stated: “This is not a great trade-off by any means, but I think the funds will make a difference. It’s a bittersweet victory.” (Black Enterprise, Oct. 3, 2013)

Subsequently, Boyd remarked about the struggle, “Our work is not finished. Black farmers still face unfair practices and struggle to gain our rightful place in America’s agriculture and food production system. Discrimination against a group of people contributes to the decline of Black farmers, as well as a loss of land.” Between 1920 and 1992 the number of Black farmers declined from 925,000 to 18,000.

Many descendants of deceased farmers are still dealing with claims, aided by the NBFA. Some were swindled by people who charged them $100 fees and pretended to file claims for them.

On March 5, 2014, in response to appeals from farmers whose claims were turned down, Judge Friedman issued an order denying reconsideration of their claims and closing the lawsuit. His ruling settled outstanding lawsuits 30 years after the NBFA first protested discrimination by the USDA, Congress and the Justice Department. However, this decision offered little to no hope for the elderly farmers who had waited years for compensation, only to be denied.

The American Agriculturalist Association stated, “Black farmers continue to be put out of farming, denied opportunities to make a living and lose land. That impacts the quality of life for them and the rural communities in which they live. … While many people in this country think that the Black farmers across this nation got justice during the Pigford Class Action, the opposite is the truth. … Black farmers are continuously denied due process, a right to have a formal hearing on the merits of their case before the Administrative Law judge of the USDA.” (press release, timeforawakening.com, July 6)

The AAA says there has been a breach of the Pigford Consent Decree and Congress will hold a hearing on the merits of the Pigford Remedy Act. The association also states the USDA is denying hearings for claims brought by Black, Native American, Latino/a and other women farmers.

Black farmers demand justice

On July 8, Black farmers from the South and other areas protested at the Supreme Court to demand justice from the courts. They sought to bring to light the unfairness of the Pigford settlement and continuing discrimination by the USDA against Black farmers.

Their demonstration raised the case of Eddie Wise and Dorothy Wise whose North Carolina farm was foreclosed. They were evicted from their property on Jan. 20 by armed federal marshals and county deputy sheriffs without being granted a hearing. The Wise family is challenging the USDA’s practice of denying Black farmers hearings before an administrative judge.

The Wise family is also petitioning the Supreme Court regarding a 2015 statute that bars all monetary claims other than for farm ownership. This includes all farm-operating loans for Pigford claimants. The USDA has circumvented the law in order to take all property belonging to affected farmers and to circumvent the statute mandating payments to relatives of deceased Pigford claimants. The question is whether the Supreme Court will prohibit these illegal tactics which affect thousands of socially disadvantaged farmers and their descendants.

The USDA is referred to as the “last plantation,” alluding to the deeply ingrained culture of racism that the agency manifested in how subsidy and loan programs were administered and whom it hired to run them.

One question raised in the July 8 protest, said the AAA, was: Are Black farmers in 2016 the new Dred Scott — denied full due process? Dred Scott was enslaved in St. Louis, Mo., and sued for his freedom in 1847. His trial lasted 10 years. In 1857, the Supreme Court denied his plea, determining that Black people were “inferior” to whites.

The court’s horrific landmark decision ruled that a Black person “whose ancestors were imported into the U.S. and sold as slaves, whether free or enslaved, has no right to sue under the Constitution in federal court as a citizen. … [and] has no rights which a white man is bound to respect.”

Additional sources: Huffington Post, May 2014; mysettlementclaims.com; Clarion-Ledger, Jackson, Miss.;

Washingtoninformer.com; University City Review, Philadelphia; indybay.org, San Francisco.