The Montgomery bus boycott — its meaning for today’s anti-racist struggle

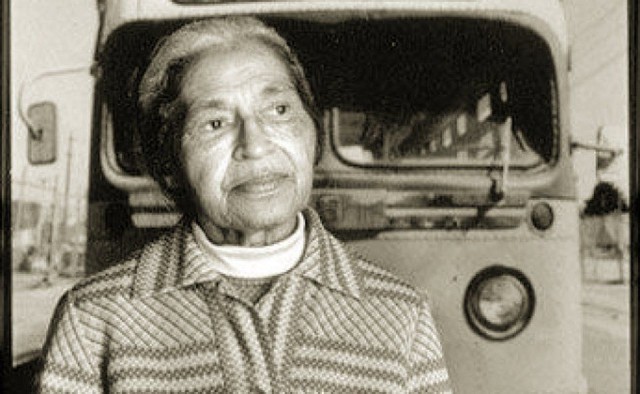

There was much discussion in early December on the 60th anniversary of the arrest of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which signaled the beginning of the modern mass Civil Rights Movement in 1955-1956.

There was much discussion in early December on the 60th anniversary of the arrest of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which signaled the beginning of the modern mass Civil Rights Movement in 1955-1956.

After Parks’ Dec. 1 arrest for refusing to relinquish her seat in the segregated area of a public bus to a white man, Montgomery’s African-American community mobilized rapidly. After Parks was charged and convicted for violating Alabama’s segregation statutes, on Dec. 5 thousands refused to ride buses. They demanded that the racist laws be overturned, and that African Americans be treated with courtesy and hired as bus drivers.

Parks, convicted in the municipal and state courts, appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in late 1956 declared the segregation laws governing public transportation unconstitutional. The Montgomery boycott lasted for 381 days and transformed the consciousness of African Americans, heightening their degree of militancy, which lasted for another two decades.

By the early 1960s, tenant farmers, students, clergy, community people and their allies had built a movement that challenged what appeared to be the last vestiges of legalized segregation and institutional discrimination. The Freedom Rides, organized during the spring of 1961, resulted in another landmark decision, outlawing segregation in interstate travel.

Just three years later in 1964, a comprehensive Civil Rights bill was passed by both houses of Congress and signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. This legislation was purportedly designed to end all forms of unequal treatment before the law involving public accommodation, education and employment.

The following year in 1965, after protracted struggle in Alabama and other states, the Voting Rights bill was passed, guaranteeing African Americans the right to vote in all elections. Over the last five decades, African Americans have been elected to thousands of political offices on the local, state and federal levels.

Despite these gains, a series of Supreme Court decisions since the late 1970s have reversed much of the progressive character of the Civil Rights bills passed during the period of 1957-1968. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were stripped of their enforcement provisions, which set the stage for tremendous setbacks in the areas of job openings, educational opportunities and access to legal due process.

Revisiting the legal abolition of slavery

Some 90 years before the Montgomery boycott, in December 1865, the 13th Amendment was ratified by Congress legally abolishing slavery in the United States. Nonetheless, now, some 150 years later, millions of African Americans are incarcerated in prisons, jails, halfway houses and are held under judicial supervision.

In his seminal work, “Black Reconstruction in America,” published in 1935 during the Great Depression, historian W.E.B. Du Bois asserted through firm material documentation that “slavery was not abolished even after the Thirteenth Amendment. There were four million freedmen and most of them on the same plantation, doing the same work that they did before emancipation, except as their work had been interrupted and changed by the upheaval of war.” (p. 188)

Du Bois goes on to note: “Moreover, they were getting about the same wages and apparently were going to be subject to slave codes modified only in name. There were among them thousands of fugitives in the camps of the soldiers or on the streets of the cities, homeless, sick and impoverished. They had been freed practically with no land [n]or money, and, save in exceptional cases, without legal status, and without protection.”

The first Civil Rights bill was introduced in Congress in 1865 but was vetoed by President Andrew Johnson. In 1866, it was reintroduced and this time a two-thirds majority overruled Johnson’s veto.

Much of the language in the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was similar to that within the later passed 14th Amendment (1868), which ostensibly granted equal protection before the law for former enslaved African men. African women were excluded, as were white women, from many civil rights during this period. Women were legally viewed as subjects of their husbands or other male family members.

Federal Reconstruction lasted until the aftermath of the compromise surrounding the contentious national elections of 1876. A process of disenfranchisement and organized terror was inflicted upon the African-American people for the remaining decades of the 19th and leading into the 20th century.

By the time of the 1954 Brown v. Topeka decision on public school desegregation, national oppression and discrimination constituted the law of the land. This law was backed up by a series of Supreme Court decisions, including the Slaughterhouse cases of 1873 through Plessy v. Ferguson of 1896. Even though African Americans had fought to end slavery during the Civil War (1861-1865), and fought also in the two imperialist wars of 1917-1918 and 1941-1945, they were still living under conditions of neoslavery and domestic colonialism.

The struggle against national oppression took on various forms. This included utilizing the legal system, petitioning and voting, the boycott (as in Montgomery), along with mass demonstrations and urban rebellions. Despite these persistent efforts, the capitalist system in the U.S. continues to be based on economic exploitation and institutional racism.

African Americans are not only being herded into failed schools which feed into the prison-industrial complex, they also suffer from jobless and poverty rates at least twice as high as the national average. The federal government and the corporations ignore the plight of African Americans, although the state claims to be a leader in the field of international human rights.

Lessons for 2015 and the struggle ahead

Today, 150 years later, an escalation in protests and civil unrest across the U.S. reveals a renewed commitment by the African-American people to overthrow national oppression, economic exploitation and institutional racism from the streets and workplaces to the campuses.

This renewed movement is also producing pioneering women and youth leaders. There is a direct historical trajectory: Ida B. Wells-Barnett, born in slavery during the Civil War in Mississippi, became a courageous journalist and organizer against lynching; the Women’s Political Caucus of Montgomery drafted and circulated thousands of leaflets calling for the bus boycott prompted by Rosa Park’s arrest; and the present period when activists such as Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi and Patrisse Cullors are coining slogans such as “Black Lives Matter,” which has become a battle cry in the fight against state violence and judicial impunity.

The anti-racist struggles were first seen on the streets outside police stations and in the shopping malls owned by some of the largest multinational corporations in the world. They have moved onto the college campuses, where the struggle over the ideas that will assess the past and chart the course for the future are being determined.

The African-American struggle continues to play a decisive role in the anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist movements. All the oppressive system has to offer the masses of workers and youth is more repression along with false promises that are only realized in the form of more refined methods of exploitation and social containment.

There are many lessons for today to be learned from this profound history of recurrent movements and ideological advancements. Only the transformation of the racist capitalist system to one based on socialism, where full equality and national liberation for the subjected peoples can be realized, will guarantee genuine peace and security within the U.S. and globally.