From a mariner, lessons of El Faro

Letter to WW

Every merchant seafarer has, at one point or another, sailed on what we call a “rust bucket.” It is pretty much exactly what it sounds like: a beat-up, old, rusty ship that shouldn’t be seaworthy, but somehow is. These ships should be put out of commission and replaced by newer, safer ships, but are still in use. Sealift Inc. is one of many shipping companies out there that are notorious for sailing these “rust buckets” around the world.

Every merchant seafarer has, at one point or another, sailed on what we call a “rust bucket.” It is pretty much exactly what it sounds like: a beat-up, old, rusty ship that shouldn’t be seaworthy, but somehow is. These ships should be put out of commission and replaced by newer, safer ships, but are still in use. Sealift Inc. is one of many shipping companies out there that are notorious for sailing these “rust buckets” around the world.

Why do these shipping companies continue to use these old, dilapidated death traps? Because the longer they can hold off on building American [U.S.] flag ships, in an American shipyard, the more money they save. By doing this, these companies have driven the American shipbuilding industry into the ground. More than half of the ships in the U.S.-flagged fleet are too old to sail, but do anyway, especially when companies have the ship, cargo and crew insured, just in case anything happens, and they have the full backing of the U.S. Coast Guard.

Even some of the newer ships are falling into disrepair because of a lack of [personnel] and the proper tools needed in order to keep a vessel in “ship shape,” due to the fact that the shipping companies don’t want to spend the time or the money on the upkeep of their own vessels. We have all seen this first hand, licensed [officers] and unlicensed sailors alike, in the form of cuts in overtime or having to fight a company tooth and nail in order to receive the proper parts or tools needed in order to get a job done.

The old-timers talk about how it was back in the old days of shipping, when they were able to accomplish so much, as far as maintenance of a ship goes, and how efficient they were at their jobs, all while being drunk or high the entire time at sea.

The truth is, they weren’t any better at our jobs than we are. It’s that they had more people! The crews were much larger back then! Everyone got paid the same wages we get paid now, but it was during the 1970s and 1980s when the cost of living was much cheaper. Once the shipping companies decided to cut crew size, they also expected the same amount of production that a crew of say 50 could accomplish from a crew size of 15.

While crews were downsized, the U.S. Coast Guard gave the shipping companies the OK to do so. And with smaller crews came more training and regulations from the Coast Guard.

After the Exxon Valdez disaster, one of the changes required all U.S.-flagged tankers to have double-bottom hulls, but for the most part, it affected those who work on the ships, not those who own them. Even after 9/11, once the Coast Guard was brought under the umbrella of “Homeland Security,” it required mariners to carry even more credentials, more documents and more training, some paid for out of our own pockets, just to be able to ship out (not to mention the endless amount of physicals and drug tests required each year by the companies and the Coast Guard).

The shipping companies are always looking for the cheapest and quickest route to deliver their cargo, regardless of the dangers (hurricanes, pirates, etc.). Meanwhile, the Coast Guard has over-regulated the shipping industry to the point of almost collapsing it. The merchant mariners are caught in the middle of it all.

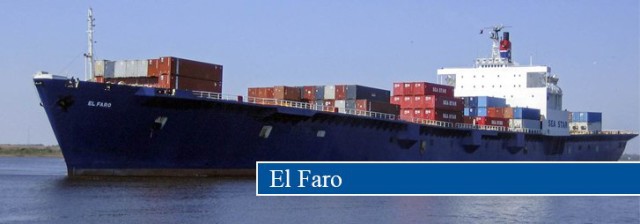

With the recent tragedy of the merchant vessel El Faro, many brothers and sisters in our industry, licensed and unlicensed, especially the families of those lost, have been devastated. Many want answers as to why a ship would sail directly into the heart of a Category 3 hurricane — especially on a 40-year-old ship whose engines were being worked on, and with open covered lifeboats and outdated safety equipment — approved by the Coast Guard.

During this whole tragedy, I don’t think it’s a good time to place blame. Right now, I just want to show my support for those lost at sea. I don’t blame the captain for the fate of the El Faro. I don’t stand by his decision either. He was doing what captains sometimes do — following company orders — and ultimately he paid the same price as everyone else aboard that ship.

All of us have been on a ship that has sailed through storms, hurricanes and heavy seas. It’s not uncommon. Sometimes the captain will refuse to go through a storm, in which case the company might even threaten to replace that captain. At other times it is the company that orders a captain not to go through a storm. In 2012, I was on a Ro-Ro [roll-on, roll-off cargo ship] drifting in the Bermuda Triangle because we were on company orders to wait for a tropical storm to pass by before we could head on into the Caribbean Sea. That “tropical storm” turned out to be Hurricane Sandy.

We don’t know the circumstances behind why the El Faro went into that hurricane. What we do know so far is that the shipping company, TOTE Maritime, has not been completely honest. Since the beginning, the company stated that, at the time, the hurricane was thought to only be a tropical storm. An email that surfaced from the second mate to her mother proved that they did have prior knowledge that they were heading into a hurricane. The company also knew that the engines were being worked on because there were private contractors aboard who were hired to make repairs on them.

The company will try and make this tragedy look like crew negligence. They will say that the captain acted on his own accord to go through the storm, putting all the crew members at risk (even though they have the power to veto any captain’s decision to go through rough weather). They will try and say there was a lack of knowledge of the lifesaving equipment on the part of the crew. Meanwhile, no mention will be made about the age and condition of that equipment, which was more than 40 years old.

I do not think there was a lack of knowledge of the lifesaving equipment. With as much training as we go through, I think that the equipment was just simply old and outdated.

However, knowledge of the safety equipment aboard our ships does need to be more democratized. Mates and engineers should not be the only ones with a working knowledge of, for example, the manual release pump aboard a free-falling lifeboat. Get the unlicensed involved. Let them do presentations on the SCBAs or fire extinguishers during “safety Sundays” instead of the mates.

During an emergency, the wiper or OS [“ordinary seaman”] might be the ones to have to drop the boat in the water. The chief cook might have to be the one to put out a fire. More faith has to be placed on the unlicensed. ABs [“able seamen”], for example, should not be seen as a rabble of mindless deck apes by the officers, but as essential to the ship’s maintenance and crew. At the same time, we, as unlicensed, need to show more initiative during drills.

One thing to remember, as licensed and unlicensed, is that these shipping companies already have insurance on the ship, the cargo and its crew. They make their money regardless of whether or not the ship makes it from point A to point B. We (officers and crew) are literally all on the same boat.

One of the reasons I love working on a ship (besides being able to travel the world by sea) is knowing the fact that EVERYONE is essential for the day-to-day operations and running of a ship. From the captain on down, and the SA [steward assistant] on up, everyone has their part to play. Take away any one element, say the SA, and the engineers might find themselves washing dishes. For those of us aspiring to become ship’s officers, and for those of you who already are, never forget this fact. Officers may have many more responsibilities on a ship, but they do not run the ship completely without the cooperation from the rest of the crew.

The shipping companies don’t fully understand the daily operations of a ship and don’t know the first thing about good seamanship, and they don’t care. Their only motivation is profit. Always keep this in mind, because it’s our lives that are being put at risk, not the company’s. It is our blood that stains these decks, not TOTE, not Crowley, not Maersk and not Sealift Inc.

What happened to the El Faro was tragic. Whatever new Coast Guard regulations are put in place after this event, they should not be placed into law in order to punish seafarers with more safety training and certifications, but should be placed on the shoulders of the shipping companies who own these rust bucket ships, not on the backs of those who work on them.

Let it be a lesson to those who would exploit our labor on the high seas. In honor of the El Faro and all hands who were onboard when she was lost to the sea, shipping companies need to be brought to accountability. All our labor unions need to come together as one (SIU, SUP, AMO, MMP, etc.) and demand: Fire up the shipyards! Build newer and safer ships! Hire bigger crews to sail those ships! This is how we should honor the 33 of the El Faro. Not only in prayer, but in our deeds as well. #ELFARO

— “El Tigre”