Many of the books and articles on this war present it as a “people’s war,” designed to preserve “democracy and freedom.” This ideological characterization might have some justification in describing the popular conception of the struggle against Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. But it certainly doesn’t explain the rivalry between the two main imperialist groupings that fought each other: Great Britain, France and the United States [the Allies] on one side and Germany, Italy and Japan [the Axis] on the other.

Nor does it explain why there were significant factions in these Allied imperialist countries who were prepared to make a deal with Nazi Germany.

In the Pacific and the struggle in East Asia, Japan was an expanding capitalist power, but not fascist. The conflict between Japan and the U.S. was clearly a struggle between two imperialisms over control of Asia.

“The Second World War: a Marxist history,” by Chris Bambery (Pluto Press, 2014), does a good job in describing the inter-imperialist rivalries and tensions, both before and after the war. Where it falls down is in evaluating the role of the Soviet Union in the struggle against fascist Germany.

The title of Chapter 6, “Russia: The Crucible of Victory,” reveals Bambery’s orientation. What he calls “Russia” was at that time, and for some time to come after World War II, the Soviet Union. He attributes its successes in resisting the German advances to loosened control over army units by the Communist Party. (p. 122)

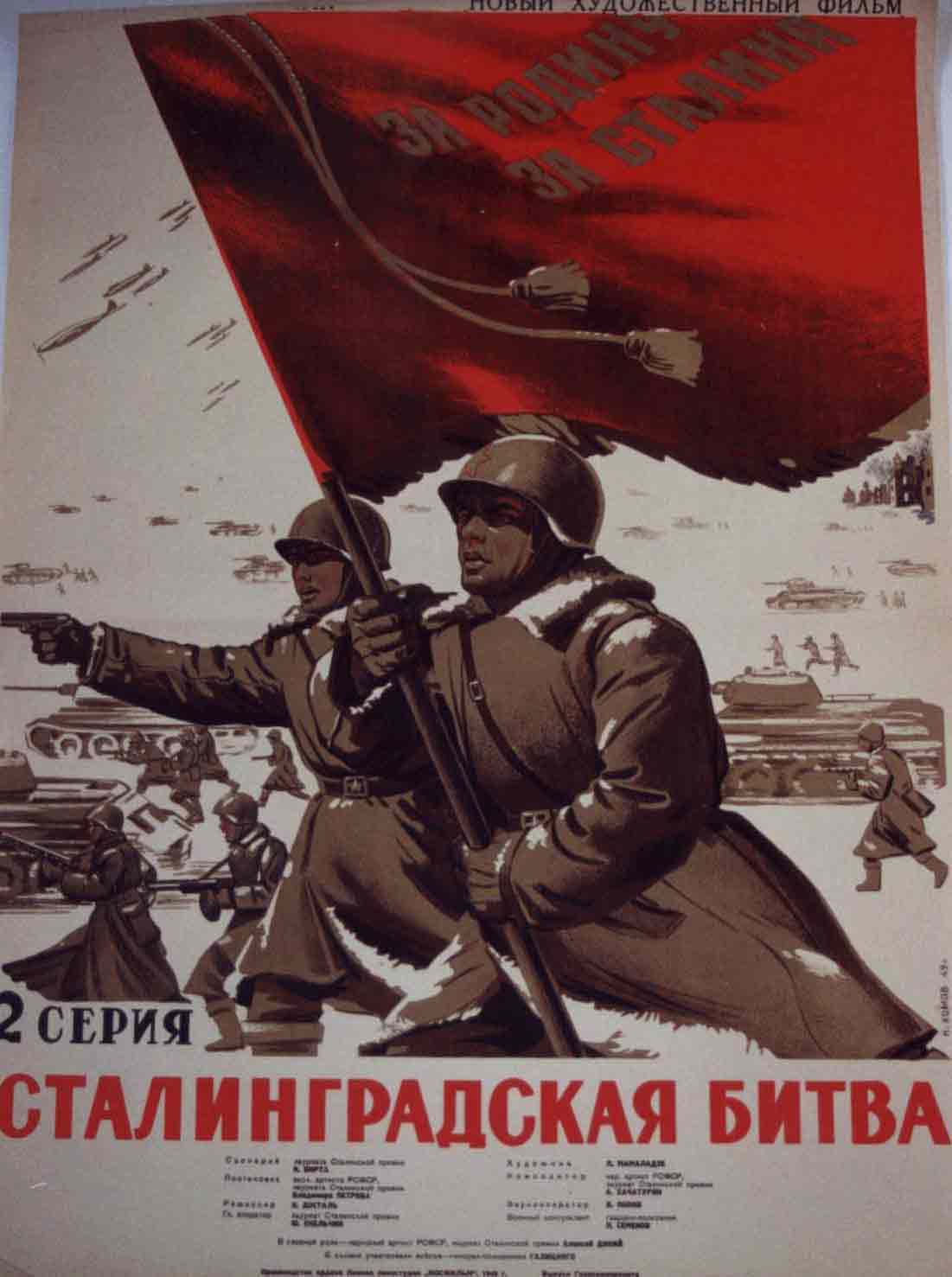

Another book, “Stalingrad: The City that Defeated the Third Reich,” by Jochen Hellbeck (PublicAffairs, 2015), disagrees. It documents that during the battle of Stalingrad, the influence of the Communists grew inside the army and membership in the Communist Party was often a reward for military valor.

Bambery, for all his biases against the Soviet Union, points out that the USSR’s social structure let it recover from the government’s grave mistake in not being prepared for Germany’s attack. In “Operation Barbarossa,” which began on June 22, 1941, Germany had launched the largest invasion in the history of warfare. Some 4 million soldiers attacked along an 1,800-mile front. But within months, the USSR was able to move 1,532 factories, including 1,360 connected to armaments, much further to the east. Using 1.5 million rail cars, it completed the job between July and November 1941.

This was one of the ways the workers used all their organizational skills to preserve their country and their social system. From then on, they worked 11 hours a day, seven days a week, far outproducing Germany and even the United States.

The German army began its battle to seize Stalingrad on Aug. 23, 1942. Hellbeck’s book draws on an unusual source. It is based on a selection from 215 interviews by Soviet historians, stenographically recorded between Jan. 2, 1943, and the end of February that year. The historians wanted to reveal the new Soviet citizen, so they interviewed troop commanders, generals, staff officers, commissars, agitators, sailors in the Volga fleet, nurses, cooks and even civilians who remained in the city.

Stalingrad was the first major battle that the Germans lost in World War II and this defeat put them on the strategic defensive for the rest of the war. It was the war’s decisive turning point in which the Germans lost a whole army.

The question was raised then, especially by the German propaganda machine but also by the anti-Soviet Western media: How could the Soviet army resist such a force? How could the raw Red Army, less than 25 years old at the time, defeat a well-oiled, well-trained, well-educated professional army?

How can it be explained why millions of people fought against the Germans until they literally collapsed from exhaustion? Why did some Red soldiers fight until their last bullet and then throw rocks rather than surrender?

At the start of the war, the British foreign service had predicted that it would take Germany four to six weeks to destroy the Red Army.

Racist Nazi view of Soviet Union

The Oct. 29, 1942, edition of the official Nazi SS newspaper Das Schwarze Korps contained an assessment of Soviet morale: “The Bolshevists attack until total exhaustion, and defend themselves until the physical extermination of the last man and weapon. … Sometimes the individual will fight beyond the point considered humanly possible.” The article tried to account for this by evoking the “laws of racial biology.” The Soviet soldiers belonged to another “race.” They originated from “a baser, dim-witted humanity.”

The article concluded by depicting the threat for Europe contained in “the power of this unleashed inferior race.” The Nazis made the battle of Stalingrad into a question of world historical destiny: “It is up to us to decide whether we remain human beings at all.”

Some prominent U.S. historians can’t understand that it was the Bolshevik Revolution that had motivated Soviet workers to defend their system. They claim that the Soviet soldiers who fought in Stalingrad did so under the lash of secret police terror. Other historians talk about Soviet soldiers as betrayed victims, and discount their statements of patriotic or pro-socialist ideals as “ideological indoctrination.”

Hellbeck’s “Stalingrad,” however, proposes a reason for the victory of the Red Army in the battle of Stalingrad: the political consciousness of the soldiers and the Soviet people, a political consciousness inculcated, confirmed and developed by the Communist Party.

Some of the stories in the interviews are striking. A typist working on orders to regiments in a division was buried when German artillery collapsed the bunker she was working in. She moved to another bunker after she was dug out, which was then likewise collapsed. She moved to a third after she was dug out again, completed her assignment and got the orders signed.

Women nurses carried sidearms, because if the Germans captured them, they were treated as sexual property of the soldiers. Over a million women wound up fighting in the Red Army, not only as nurses, but also as intelligence officers, mechanics, snipers, cooks, typists and pilots.

Communist agitators and political commissars saw their primary purpose as maintaining morale and inspiring even greater heroism because the soldiers and workers understood how the battle of Stalingrad fit into the worldwide struggle. Every division, brigade, regiment and even smaller units had a newspaper of some sort, which explained what was going on and pointed out acts of heroism.

What is truly impressive about the interviews in “Stalingrad” is that they give a multidimensional point of view — from the Communist cadre who did the ideological education work to the soldiers who received it.

The battle of Stalingrad was a decisive turning point in World War II and the Soviet Communist Party played an essential part in the Red Army’s defeat of Nazi Germany.

This statement was recently issued by over 30 groups. On Friday, March 28, Dr. Helyeh…

By Jeri Hilderley I long for peace and ease as stress and anxiety overtake me.…

Los siguientes son extractos de la declaración del Gobierno de Nicaragua del 9 de abril…

The following are excerpts from the statement of the Nicaraguan government on April 9, 2025,…

The following is a statement from the organization Solidarity with Iran (SI) regarding the current…

By Olmedo Beluche Beluche is a Panamanian Marxist, author and political leader. This article was…