150 years after U.S. Civil War, anti-racist struggle continues

Confederate Army forces retreated from Richmond, Va., in early April 1865 in the face of advancing Union troops, many of whom were Africans.

Soon the Union forces reached the last capital city of the secessionists. The Confederates had set fire to large areas of the city, but the African troops helped to restore order in those areas.

This historic anniversary in United States history is being recognized this year. Nonetheless, the conclusion of the Civil War, which lasted from 1861 to 1865, represents the beginning of efforts to reconstruct the U.S. without slavery and national oppression — a quest that has still not been realized in 2015.

The Confederate military forces believed that if they abandoned Richmond they could continue the war against President Abraham Lincoln, but their cause was lost. Absent a central focus and with demoralization widespread among the secessionist troops, they were doomed to disorganization without real reason to continue the fight.

Just a few days later, the Confederates surrendered to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox. The conclusion of the Civil War saw the legal end of slavery with the passage of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, setting the stage for Reconstruction.

Post-Civil War struggle for Reconstruction

Even with the passage of the 13th Amendment, the state governments established from 1865 to 1867 were dominated by former Confederates, who passed “Black Code” laws that maintained white dominance and denied due process to African people. It was not until the national election of 1866 and the actions of the Radicals and their allies in Congress during 1867 that some movement took place in granting citizenship rights to Africans and organizing the South into military districts.

Then President Andrew Johnson was outraged by Congress assuming the authority over Reconstruction. Later he barely escaped impeachment and by the end of 1867 fell from political grace. By the time he left office at the end of 1868, Johnson had issued a general amnesty for the former Confederate leadership.

During this period the 14th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified granting citizenship rights to former slaves. By 1869, the 15th Amendment gave voting rights to African-American men. It was not until 1870 that the first African Americans entered the U.S. Congress — Joseph H. Rainey from South Carolina and Hiram Revels of Mississippi.

However, at the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865, the Ku Klux Klan was formed in Tennessee by Nathan Bedford Forrest, a former slave trader and Confederate general. Forrest had been responsible for one of the most egregious atrocities of the war, committed in April 1864 at Fort Pillow, Tenn., where hundreds of enslaved African troops as well as Union whites were massacred. Starting in 1865, the Klan organized openly and conducted a ruthless terror campaign in all the states throughout the South. Soon it was battling the Reconstruction process.

Eventually in 1876, after a disputed national presidential election, the federal government largely abandoned the Reconstruction policy. Although in several states including Tennessee, South Carolina and North Carolina, African Americans would continue to hold office through the 1880s and 1890s, by the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries the experiment in democracy was completely overthrown.

By 1877, the federal government had withdrawn its forces from the South, prompting decades of reaction characterized by peonage, sharecropping, tenant farming, lynching and repressive laws. The failure of Reconstruction ushered in another century of national oppression.

Lynchings reinforce legal segregation

Lynching became common throughout the South and many areas in the North. Thousands of African Americans were summarily beaten, tortured and killed.

Peonage, sharecropping, tenant farming and contract labor laws created conditions analogous to those that prevailed during slavery. In 1896, the Supreme Court in its Plessy v. Ferguson decision consolidated federal law in favor of legalized segregation.

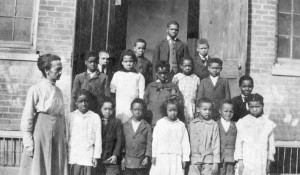

It would take until 1954 for this decision to be reversed, with specific reference to public education. A mass Civil Rights struggle beginning in December 1955 set the stage for a renewed effort to eradicate U.S. apartheid.

The first federal law in support of equality since Reconstruction was passed in 1957, relating to the ability of the Justice Department to enforce voting rights. By 1960, students took the lead through the sit-in movement and the Freedom Rides to militantly make a move toward the eradication of legalized segregation and for universal suffrage.

Continuing relevance of Civil War and Reconstruction

It is now 50 years since the height of the African-American national movement characterized by mass demonstrations and urban rebellions, which prompted the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But Black people are still not fully liberated. A renewed struggle against racism and national oppression emerged during 2014 in response to heightened police repression and economic exploitation.

A century and a half later, we have the advantage of looking back at the historic developments during the Reconstruction and Civil Rights eras of African-American history. At present the world capitalist system, headed by the U.S., is facing the worst crisis since the Great Depression.

Even though monumental changes have taken place in the political and economic systems in the U.S. and the world since the slavery period, the U.S. is still fundamentally a class-dominated society, with the corporations and banks controlling all social institutions. The whites-only signs have been removed, but the barriers to social progress and genuine freedom remain.

While a president of African descent, Barack Hussein Obama, now sits in the White House, police and other agents of the racist-capitalist state can kill the oppressed at will. Demands for the prosecution of cops who violate the rights of African Americans are routinely ignored.

Therefore, the contemporary phase of the struggle must be designed to overturn racism, national oppression and economic exploitation at its roots. A new system of relations between national groups emphasizing the right to self-determination and full equality has to emerge if true liberation is to be achieved.

To wage such a campaign for total freedom, the oppressed must be organized independently of the capitalist- and imperialist-dominated parties. Only a party of the working class and the oppressed can assure the eradication of injustice and class oppression.