African Burial Ground exposes slavery

Yes, slavery existed in the North, too. New York was one of the largest centers of slaveholding in the U.S. In 1991, a gravesite was discovered during a dig for the construction of a new federal building in New York City’s Lower Manhattan area. It was 300 years old then. An 18th century map of the area revealed the site was the location of a “Negros Burial Ground” covering six acres, approximately five city blocks.

Yes, slavery existed in the North, too. New York was one of the largest centers of slaveholding in the U.S. In 1991, a gravesite was discovered during a dig for the construction of a new federal building in New York City’s Lower Manhattan area. It was 300 years old then. An 18th century map of the area revealed the site was the location of a “Negros Burial Ground” covering six acres, approximately five city blocks.

Africans began arriving in New Amsterdam, a Dutch settlement, in 1625. They were forcibly brought there from the Caribbean and Africa. In 1664, New Amsterdam became the British colony of New York.

Thousands of enslaved Africans and the small number of free Black people were buried in the Burial Ground. They were forbidden to inter their dead in any church graveyard or within the boundaries of the settlement. Other restrictions were also placed on them. For instance, they could not bury their dead at night, as was the African burial ritual custom; and no more than 12 people were allowed in a procession or at the gravesite. In 1673, the burial ground land was sold for house lots, and in 1795 the burial ground was closed.

When the African-American community became aware of the gravesite discovery, they and local politicians protested and demanded a halt to further digging. They appealed to then Mayor David Dinkins, who ordered construction halted in order to investigate the findings and preserve the site.

Excavation by archaeologists found the remains of 419 bodies of women, men and children. It is estimated that many thousands more bodies of African and Indigenous peoples exist under buildings and sidewalks throughout the area. In 1999, nine mostly intact African skeletons were found during construction of a new sidewalk nearby.

In the disintegrated coffins, some skeletons were nearly complete; some were buried with pins, beads, buttons and shells, in the African tradition. They were sent to a laboratory at the Historically Black College of Howard University in Washington, D.C., where the federal government had contracted for anthropologists, scholars and scientists to examine the bone fragments and relics.

Their research indicated that nearly half the graves contained children, suffering from malnutrition and many with bone deformities from physical labor. Adult bone injuries were attributed to strenuous physical labor and brutality. All bodies revealed short life spans.

Honoring the ancestors

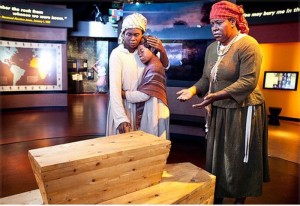

In 1993 the African Burial Ground was designated a NYC Historical Landmark. On Oct. 1, 2003, the bodies were returned to New York City in new wooden coffins traditionally carved in Ghana. Concurrently, some of the coffins were ceremoniously received with “Rites of Ancestral Return” commemorations in Washington, D.C.; Baltimore, Md.; Wilmington, Del.; Philadelphia, Pa; and Newark, N.J. where slave labor had been used to clear the land, build roads and construct infrastructure for European colonization.

In New York City, the coffins arrived by boat at the foot of Wall Street, the former site of an African Slave Market, where slave labor built an actual wall to keep out the Indigenous. Upon arrival, a ceremony paid tribute to the ancestors with interfaith prayers, African drumming, singing and dancing, followed by a libation, the singing of the “The Negro National Anthem,” a welcome and introduction.

African dignitaries, community organizations, politicians, artists, groups of school children, South African healers and spiritual leaders, New Yorkers and out-of-town visitors were present. High school students, including those from South Africa, participated in singing performances and shout-out calls for respect, honor and dignity. “A Letter for the Children” by South African Bishop Desmond Tutu was read. Speakers included the South African Ambassador to the U.S.

The coffins left Wall Street in large horse-drawn, glass-enclosed carriages, followed by a large procession through the streets to the Burial Ground.

The next day’s ceremony at the Burial Ground began similarly, included spoken word and several readings of poetry by the late African-American poet Langston Hughes. Several tributary statements were made and others read, including one from Nigeria’s President Chief Olusegun Obasanjo. Soil from the Burial Ground containing ancestral spirits was collected to be taken back to Freedom Park, a final resting place of anti-apartheid fighters in South Africa. After closing remarks, a benediction was given by an Indigenous community representative.

The coffins were then lowered into the ground, with flowers and written messages to the ancestors. Subsequently, all coffins, many in crypts, were reburied in their permanent resting place.

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem organized the ceremonies celebrating the heritage of Africans in the U.S., their lives, culture and the role they played in building the country.

In 2006, the Burial Ground was declared a national monument; in 2007 a permanent memorial sculpture was dedicated on the site. Project materials and records were transferred in 2009 from the National Park Service and Army Corps of Engineers to the Schomburg Center. Samples of the Burial Ground remain at Howard University. In 2010, following completion of the new federal building nearby, the African Burial Ground Visitors Center was opened, which contains permanent artworks and an installation about the history of slavery and Black Americans in Lower Manhattan.

Sources for this article include “A Burial Ground and Its Dead Are Given Life” (New York Times, Feb. 26, 2010) and “The African Burial Ground” at gsa.gov/portal/content/101077.