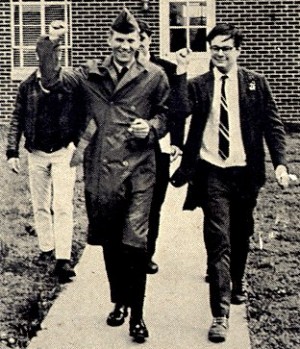

Andy Stapp, a thorn in the Pentagon’s side

Andrew Dean Stapp could have been an archaeologist, a historian or even a stand-up comic. Instead, he chose to focus his broad spectrum of talents on fighting the military brass and ending the Vietnam War.

Andy, as everyone called him, died on Sept. 3 at the age of 70. When only 23 years old, while a private at Fort Sill, Okla., he had gathered together a group of active-duty GIs to form the American Servicemen’s Union. This organization drew up a 10-point program of demands ranging from the right to refuse illegal orders — like the order to fight in Vietnam — to the election of officers by the ranks and an end to racism and sexism. It grew into the most audacious thorn in the Pentagon’s side.

At its height the ASU had enrolled thousands of card-carrying members scattered on bases all over the world, in all branches of the U.S. military. Its newspaper, The Bond, was read in trenches, cockpits and submarines. It was mailed out to many thousands of active-duty military personnel and then passed hand-to-hand to countless thousands more. Some mailroom clerks subscribed their entire units to this unabashedly radical newspaper. Its centerfold was devoted to unflattering descriptions of brutal officers and noncoms who had been nominated by their men to be “Pig of the Month.”

Stapp was court-martialed twice and then discharged from the Army in early 1968 after a field board hearing that declared him “undesirable.” The support he received from the soldiers in his unit was amazing. Many testified in his defense. Their testimony clearly convinced the brass that throwing Stapp in the stockade would probably instigate a rebellion. He also had extremely capable free legal defense provided by Atty. Michael Kennedy of the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee. A few years later, after winning a civilian court suit, his discharge was changed to “honorable.”

Stapp was a prodigious reader and walking encyclopedia of knowledge, both contemporary and historical, to the end of his life. He educated everyone around him with a running commentary on current events that was factual but delivered with a deadpan, biting wit.

His narrative style can be experienced in his book “Up Against the Brass,” published in 1970 by Simon & Schuster, in which he related the story of the ASU and gave some of his personal history.

After graduating from high school, it was a trip he made with a group of archaeologists to digs in Egypt that first made him aware of the terrible legacy left by colonialism. From childhood he had admired the great civilizations of ancient Rome and Egypt. He saw firsthand how British colonial rule had left the people of Egypt impoverished and ground down.

His first act of rebellion against the Vietnam War was on Oct. 16, 1965, when he burned his draft card, along with a group of fellow students at Penn State. But he soon saw that such symbolic acts were not enough. So the following May, he showed up for induction and joined the Army — with the intention of organizing among the GIs. He succeeded beyond his wildest dreams.

He wrote in “Up Against the Brass”:

“We talked to everyone who would listen. Soon the entire battalion knew our views. Only a handful showed hostility. Often in the barracks, after lights-out, we would kid about the war. Dick Wheaton, a marvelous mimic, could sound exactly like Lyndon Johnson. He would pretend he was LBJ holding a press conference and the guys would ask questions.

“‘Mr. President, why are we in Vietnam?’

“‘Son, to save it from the Communists. Ah want yuh to know that if we have to destroy that country to save it, we will.’

“‘Mr. President, are you going to send additional troops to Vietnam?’

“‘Our commitment is firm, son, firm. Ah’m not gonna hide mah tail between mah legs and run. Ah’m willin’ to fight to the last drop of yore blood to achieve peace.’

“‘Mr. President, what do you think of the GIs at Fort Sill?’

“‘Those Communist GIs are a thohn in mah side.’”

Supported other rebellious GIs

After being discharged from the Army, Stapp made many trips to support soldiers who were fighting the racist, sexist, top-down rule of the military machine. He went to Fort Hood, Texas, to defend the Fort Hood 43 — 43 Black GIs who sat down and refused to be sent to Chicago in 1968 to suppress demonstrations at the Democratic National Convention there. He organized support for a group of soldiers at Fort Dix, N.J., who were being court-martialed for a rebellion in the stockade. One of the GI leaders, Terry Klug, had organized a powerful chapter of the ASU among the imprisoned soldiers.

After the war finally ended, Stapp continued the struggle for justice and equality as a writer for this newspaper, Workers World. Readers tell us that in those days the first thing they looked for each week was his column, which raked the ruling class and its stooges over the coals for their crimes against the workers and oppressed — using his unique and powerful brand of humor.

He joined Workers World Party — the “parent” organization of Youth Against War & Fascism — and spoke at many Party conferences. He had honed his oratorical skills speaking at campuses during the war in order to raise funds for the ASU.

For the last 30 years of his life, he was a history teacher at the Hudson School in Hoboken, N.J., where he inspired new generations to question all the self-serving propaganda that is dished out by the establishment as “education.” He was so beloved by his students that, year after year, he was elected by the graduating class to address their commencement celebration.

A personal note: This writer was among the group from Youth Against War & Fascism who drove from New York City to Oklahoma in July 1967 to attend Andy’s second court-martial.

We didn’t make it to the trial — we were all barred from the base and two of us, Maryann Weissman and Key Martin, were arrested. They had been in Lawton, Okla., for several months sending out press releases and helping the GIs in various ways. They each served six months in federal penitentiaries just for trying to enter the base to attend what the Army claimed was an “open” court-martial. One of our group given a bar order that day was Eddie Oquendo, who later went to prison for resisting the draft.

Once the court-martial was over, those of us not in jail got to meet Andy and other GIs, who regaled us with descriptions of the farce that had just occurred. Andy and I met again in New York when he was on leave and we were married in October 1967. Two years later, after he had been put out of the Army, our daughter, Katherine Stapp, was born. While we haven’t lived together for years, I still have Andy’s ASU membership card from 1971, which lists the 10 demands and the slogan: “To win a Bill of Rights for rank-and-file servicemen and women.”