Six unelected men deliver blow to Civil Rights

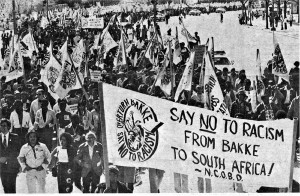

35,000 marched on Washington D.C., in April 1978 to ‘Beat Back Bakke,’ an attack on affirmative action.

The unelected U.S. Supreme Court has delivered a sharp blow to rights won through mass struggles against racism.

In a six-to-two decision on the Schuette vs. BAMN case on April 22, the high court upheld a Michigan referendum about a constitutional amendment that placed a ban on affirmative action. The so-called “Michigan Civil Rights Initiative” of 2006 actually reversed the legal and political principles that had guided the movement for equality from the 1950s through the 1970s. The ruling will also have an impact on seven other states, which have similar bans.

The court decided that it possessed no jurisdiction to overturn the Michigan vote, which banned race and the history of national discrimination as factors in admissions to higher educational institutions. The state’s vote and other initiatives have resulted in drastic declines in the number of African-American and Latino/a students at universities and colleges around the state and the country.

Not only did the high court’s majority uphold Michigan’s anti-affirmative-action vote, it rejected a federal appeals court decision that said the adoption of such a state law violates the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. That amendment ostensibly guaranteed equal protection under the law.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, often considered the “swing vote,” summed up the conservative majority view, which said that such considerations of racism and past discrimination were not needed and were unconstitutional.

Kennedy said, “In a society in which those lines are becoming more blurred, the attempt to define race-based categories also raises serious questions of its own. Government action that classifies individuals on the basis of race is inherently suspect and carries the danger of perpetuating the very racial divisions the polity seeks to transcend.” (supremecourt.gov, April 22)

But Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the only Puerto Rican jurist, gave a dissenting opinion that abhorred the decision. Sotomayor recognized that her career path had been directly related to the affirmative action programs that helped her, a Latina from the Bronx, get into Princeton University and Yale Law School.

Sotomayor stressed that the majority’s refusal “to accept the stark reality that race matters is regrettable. We ought not to sit back and wish away, rather than confront the racial inequality that exists in our society.”

Deception and racism in Michigan vote

The anti-affirmative-action referendum’s placement on the Michigan ballot had been based on massive deception through a well-financed political campaign.

A petition campaign was launched in 2006 to place the initiative on the ballot; canvassers were paid for collecting signatures. Many were instructed to falsely say that this initiative would advance equal opportunity by changing the Michigan state constitution to bar discrimination.

But opponents launched a challenge to the ballot initiative. They claimed it was not the intent of most petition signers to ban affirmative action. However, the state elections commission and the courts upheld the initiative, which passed during the 2006 statewide elections.

Bourgeois law still does not recognize the historic national oppression of African Americans, Latinos/as, Asians and Native peoples. The prevailing view in the capitalist media is the racist argument that any advancement made by oppressed nations constitutes “reverse discrimination” against the dominant oppressor nation.

This Supreme Court decision is part of an effort to reverse the major political and social gains of the Civil Rights, Black Power and women’s movements that emerged after World War II. In 1954, the historic Brown v. Topeka decision of the Supreme Court had ruled that “separate but equal” facilities for students in public education were inherently unconstitutional.

The Brown v. Topeka ruling reversed the Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896 — which during the era of Jim Crow and lynching had provided a legal rationale for “second-class citizenship” for African Americans. Through a series of political and legal campaigns led by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and others, institutional discrimination was eventually outlawed in both higher education and from kindergarden through 12th grade.

Struggle won affirmative action

Nonetheless, it took a mass Civil Rights and Black Power movement — beginning in 1955 and continuing through the early 1970s — to bring real affirmative action programs into existence.

With the advent of urban rebellions from 1963 to 1970, the impetus for implementing such policies was accelerated.

The administration of Lyndon Johnson, responding to the militancy of the African-American struggle and seeking peace at home in order to wage war in Southeast Asia, shepherded the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 through the U.S. Congress.

It was Johnson who noted in a commencement address at Howard University in 1965 that simply passing laws would not be enough to make a dent in historical institutional discrimination and used the term “affirmative action.” Later, the right wing used the term to push back against the changing social character of race relations in the United States, a country built on the genocide of Indigenous Americans, enslavement of Africans and colonization of large sections of the Mexican population in the Southwest.

Johnson said, “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say you are free to compete with all the others, and still just believe that you have been completely fair.”

In September 1965, Johnson issued Executive Order 11246 to enforce a policy of nondiscrimination. In 1967, the order was amended to bar discrimination against women in hiring.

Earlier, the Kennedy administration had issued Executive Order 10925, mandating that federal contractors not only end discrimination but take “affirmative action to ensure” compliance. It also mandated penalties for noncompliance with anti-discriminatory policies.

However, in the late 1970s, the reactionary Bakke case reached the Supreme Court. It challenged quotas and timetables intended to implement nondiscriminatory policies. In 1978, the high court’s ruling on Bakke lessened the impact of previous executive orders and legislation that had mandated nondiscriminatory policies.

Anti-affirmative-action campaigns in California, Texas and Florida, as well as Michigan, have largely eliminated the institutional commitment to nondiscrimination. Demonstrations by African-American students at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor are calling for the elite institution to establish programs to recruit more people from this oppressed community.

What is needed to make these demands a political force is to initiate a national movement against institutional racism that would encompass the declining social status of the nationally oppressed, who are still suffering from disproportionate rates of unemployment and poverty.

The gains of the 20th century were the result of the mass struggles of African Americans, Latinos/as, other oppressed peoples and their allies. It will again require the mobilization and organization of the masses of people in a militant program of resistance and fightback to reverse these setbacks.