Yet what is often not recognized is the more-than-a-century-old linkage between the South African and African-American peoples that extends back even prior to the founding of the South African Native National Congress in 1912, later renamed the African National Congress (ANC) in 1923.

One of the SANNC founders, Pixley ka Isaka Seme, was born in Natal in 1881. At the age of 17 he was able to travel to the United States to study.

He called for unity, noting, “My conviction is that here in Africa, as in America, the Africans should refuse to be divided. I cannot ever forget the great vision of national power which I saw at Atlanta, Georgia in 1907 when the late Dr. Booker T. Washington L.L.D., presided over the Annual Conference of the Negro Business League of America with delegates representing all Negro enterprises in that New World and representing 20 million Africans in the United States of America, the most advanced of my own race.” (Seme pamphlet, “The ANC, Is It Dead?” 1932)

John L. Dube (1871-1946) was also a co-founder of the SANNC, and through his connections with the U.S.-based African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded by African Americans in Philadelphia, he was able to travel to the U.S. and study.

Dube returned to South Africa to establish a school inspired by Tuskegee Institute founded by Booker T. Washington. Dube wrote he “was inspired by Washington’s initiatives, and after meeting Washington in 1897, he returned to South Africa and founded the Zulu Christian Industrial Institute (1901), renamed the Ohlange Institute. Like Tuskegee, Dube’s Ohlange focused on improving blacks’ labor efficiency and increasing the skills of black laborers. This assisted the indigenous African population by giving them more opportunities and increasing their abilities.” (Oberlin.edu)

Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje, a SANNC leader, met with Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. Du Bois in 1921. Plaatje wrote articles for the Universal Negro Improvement Association newspaper, The Negro World, founded by Garvey and circulated broadly throughout the U.S. and the world.

During the 1940s, the formation of the ANC Youth League was led by Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Anton Lembede and others. A program of action was drafted in 1949 transforming the ANC into a mass political organization.

Solidarity actions carried out by the Council on African Affairs in 1946 during the Rand Miner’s Strike raised money and material aid to assist the South African workers. The CAA was founded by Paul Robeson, William Alphaeus Hunton, and would later enjoy the membership of DuBois.

During the course of the 1952-1956 Defiance Against Unjust Laws Campaign led by the ANC, the Congress of Democrats, the Natal Indian Congress, the Colored People’s Organization, the Federation of South African Women and the South African Congress of Trade Unions developed tactics employed by South Africans that would influence the mass Civil Rights Movement of the late 1950s and 1960s.

Anti-apartheid struggle inspires U.S. solidarity

In 1962 the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. made a joint statement with the then-ANC-President Chief Albert J. Lutuli. King actively supported the struggle of the South African people against apartheid. (Electronic Intifada, March 25, 2007)

The statement reads, “In 1963 the UN Special Committee against Apartheid was established and one of the first letters the committee received was from Martin Luther King, according to Nigerian ambassador Leslie O. Harriman. Together with the winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1960, the ANC leader Chief Albert J. Lutuli, Martin Luther King made an ‘Appeal for Action against Apartheid’ on Human Rights Day, 10 December 1962.”

The appeal reads: “Nothing which we have suffered at the hands of the government has turned us from our chosen path of disciplined resistance, said Chief Albert J. Lutuli at Oslo. So there exists another alternative — and the only solution which represents sanity — transition to a society based upon equality for all without regard to color. Any solution founded on justice is unattainable until the Government of South Africa is forced by pressures, both internal and external, to come to terms with the demands of the non-white majority. The apartheid republic is a reality today only because the peoples and governments of the world have been unwilling to place her in quarantine.”

On March 19, 1965, 750 people protested in New York City at the Chase Manhattan Bank on the fifth anniversary of the Sharpeville massacre. The demonstration was organized by the Students for a Democratic Society and gained the support of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Congress on Racial Equality, Pan-African Students Organization of the Americas and other organizations. The aim of the demonstration was to demand withdrawal of financial support for the apartheid regime by the U.S.-based financial institution. (allacademic.com)

In June 1967, a SNCC-led delegation consisting of International Affairs Director James Foreman and attorney Howard Moore attended an international conference in solidarity with the people of Southern Africa in Kitwe, Zambia. Forman later addressed the 4th Committee on Decolonization at the United Nations where he expressed support for the armed struggle in South Africa and Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe). (“The Political Thought of James Forman,” 1970)

By the mid-1980s, the solidarity movement with South Africa inside the U.S. had reached unprecedented levels. The primary foci were a demand for total divestment from corporations doing business with South Africa, the isolation of all racist South African business dealings inside the U.S. and solidarity with the liberation movements fighting settler-colonialism in South Africa and Namibia.

Student organizations on campuses throughout the U.S. began to take decisive actions through demonstrations, sit-ins and speaking engagements by representatives of liberation movements. Municipalities began to be pressured to ban all economic and political dealings with apartheid.

Organizations such as the Patrice Lumumba Coalition in New York, the U.S. Out of Southern Africa Network, the American Committee on Africa, the Pan-African Students Union and many others took a leadership role in these efforts. The work of such organizations on the grassroots, academic, workplace and legislative levels led to the passage of the Anti-Apartheid Act of 1987, the first federal legislative sanctions imposed on apartheid South Africa.

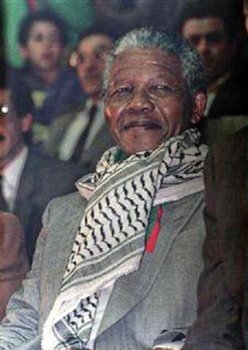

When Nelson Mandela visited the U.S. in June 1990 after being released from 27 years in prison, he was met with a tumultuous welcome. In New York, Detroit and other cities tens of thousands of African Americans and other progressive forces came out to see him and to express their solidarity.

Memorial programs for Mandela have been held throughout the country over the last three months. There is much to be learned from the struggles of the South African people and the international solidarity movement that grew up in its defense.

This statement was recently issued by over 30 groups. On Friday, March 28, Dr. Helyeh…

By Jeri Hilderley I long for peace and ease as stress and anxiety overtake me.…

Los siguientes son extractos de la declaración del Gobierno de Nicaragua del 9 de abril…

The following are excerpts from the statement of the Nicaraguan government on April 9, 2025,…

The following is a statement from the organization Solidarity with Iran (SI) regarding the current…

By Olmedo Beluche Beluche is a Panamanian Marxist, author and political leader. This article was…