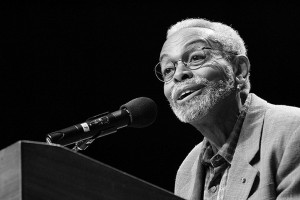

Amiri Baraka honored

Amiri Baraka — an award-winning poet, playwright and Black revolutionary — died on Jan. 9 at the age of 79 in Newark, N.J., following a short illness. He was a supporter of many left-wing causes, including the ongoing struggle to free political prisoners like Mumia Abu-Jamal. In 2009, the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture held a 75th birthday tribute event for Baraka in Harlem, N.Y. A memorial and funeral were held for Baraka at Newark Symphony Hall on Jan. 18, where thousands of people attended to celebrate his life and immeasurable political and cultural contributions. The following are excerpts from the obituary that was distributed at the memorial.

Amiri Baraka (aka Imamu Baraka, aka LeRoi Jones) was born Oct. 7, 1934, in Newark, N.J., to the late Coyt Leroy Jones and Anna (Russ) Jones. He left Howard University a semester short of graduating and later joined the Air Force, where he was discharged because of his affiliation with reading material that was considered subversive.

After leaving the Air Force, Amiri moved to New York, where he took an editorial job at a music magazine, The Record Changer, and settled in Greenwich Village. He co-founded a literary magazine, Yugen, which published his work and that of Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and Jack Kerouac. With the poet Diane di Prima, he established and edited another literary magazine, The Floating Bear. He also started a small publishing company, Totem Press, which in 1961 issued his first collection of verse, “Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note.”

“Mr. Jones considered himself a largely apolitical writer at first. His poetry was concerned more with introspection, but he was radicalized by traveling to Cuba in 1960, the year after Fidel Castro came to power, to attend an international conference featuring writers from an array of third world countries. As a result, he later said that he came to believe that art and politics should be forever linked.” — Margalit Fox, New York Times

His political awakening was soon manifested in his work. His first major book, “Blues People,” published in 1963, placed black music — from blues to free jazz — in a wider socio-historical context.

Baraka’s reputation as a playwright was established with the production of “Dutchman” at Cherry Lane Theater in New York on March 24, 1964. The controversial play subsequently won the Obie Award for Best Off-Broadway Play and was made into a film in 1967. The critically acclaimed play was revived by Cherry Lane Theater in January 2007 and has been reproduced around the world.

In 1965, Baraka moved to Harlem where he founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School. BARTS lasted only one year but had a lasting influence on the direction of Afro-American Arts. BARTS sent five trucks a day into the Harlem community, full of artists and poets, to display artwork and perform poetry readings, music and drama. Performances were given in changed locations each day. Vacant lots, playgrounds and housing projects pushed art that would be “Black as Bessie Smith,” mass-based, revolutionary and taken to the people; reflecting the intensity of the entire Black Liberation Movement. In 1966, when BARTS was dissolved, Baraka returned to Newark, his hometown.

In 1966, Amiri married Amina Baraka, formerly Sylvia Robinson. Together they inaugurated The Spirit House and the Spirit House Movers that brought drama, music and poetry from across the country to Newark. The Barakas founded the Committee for Unified Newark and the Congress of Afrikan People. Both CFUN and COAP led support in the election of Kenneth A. Gibson as the first Black mayor of a major northeastern city, spearheaded by the 1972 Gary, Ind. convention. In 1968, Baraka co-edited “Black Fire: Anthology of Afro-American Writing,” with Larry Neal.

Amiri and Amini Baraka founded Kimako’s Blues People, a multimedia arts space, from a small theater in their Newark home. Amiri founded the jazz/poetry ensemble Blue Ark, which played at the Berlin Festival and throughout the U.S. His jazz opera, “Money,” with Swiss composer, George Gruntz, was performed in part at George Wein’s New York Festival in the early 90s. “Primitive World,” with music by David Murray, was also performed in part at same New York Festival, at the Nuyorican Poets’ Cafe and the Black Drama Festival in Winston Salem, N.C. His Bumpy: Bopera, with music by jazz drummer, Max Roach, was performed in 1991 at Newark Symphony Hall and at San Diego Repertory Theatre. Amiri founded the New Arkestra, a big band working to produce a living archive of this music.

In the fall of 2002, Baraka, who had been named New Jersey Poet Laureate by then Gov. James McGreevy, came under fire from the New Jersey Office of the Anti-Defamation League, the New Jersey Assembly and others after a reading at the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation’s annual poetry festival in Stanhope, N.J., of his controversial poem, “Somebody Blew Up America,” about the 9/11 attacks. Baraka’s $10,000 stipend was rescinded and the poet laureate position eliminated in 2003 by Gov. McGreevey, who resigned in disgrace in 2004. In 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear Baraka’s case in which he asserted his First Amendment rights were violated. Baraka was also the poet laureate of the Newark Public Schools in 2002.

Amiri Baraka taught at Yale University, Rutgers University and George Washington University and spent 20 years on the faculty of the State University of New York in Stony Brook, where he retired as Professor of Africana Studies in 1994. He was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1995.

His book of short stories, “Tales of the Out and the Gone,” was published in 2007. “Home,” his book of social essays, was re-released by Akashic Books in 2009. The Before Columbus Foundation selected Baraka’s “Digging: The Afro-American Soul of American Classical Music” as winner of the 31st Annual American Book Awards for 2010. In 2012, Baraka received the Jazz Journalists Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award.