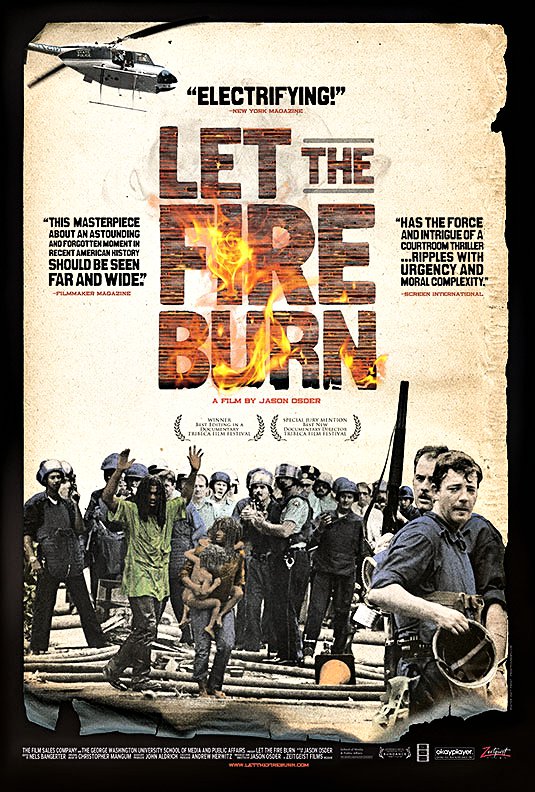

Osder’s film, 10 years in the making, is comprised completely from archival footage — including news broadcasts, televised coverage of investigative hearings after the bombing and videos taken around the MOVE house in the Powelton Village area of Philadelphia, the scene of a police siege and assaults from 1977 to 1978.

For more than a decade the mostly Black, radical group MOVE was targeted and harassed by police and city officials for its stance against racism and police brutality. MOVE members experienced hundreds of arrests and beatings by Philadelphia police. One shortcoming of the film is that this background is not supplied. Osder focuses more on the group’s lifestyle than on their political outlook.

In 1977, after one police attack left a MOVE child dead, the group publicly displayed weapons to defend their home. Police responded with a 15-month siege to evict MOVE that ended on Aug. 8, 1978, when police attacked with assault weapons and water cannons.

The police brutally beat and kicked MOVE member Delbert Africa, one of nine MOVE members arrested that day and sentenced to 30 to 100 years in prison in connection with the death of one police officer.

Fire as a weapon

The film shows how MOVE used their new headquarters at 6221 Osage Ave. in the Cobbs Creek area of West Philadelphia, a Black neighborhood, to air their grievances with the city and to broadcast information to neighbors about the MOVE 9. Fueled by their decade-long conflict, but using the excuse that neighbors had complained, police staged a second attack on May 13, 1985.

Although seven adults and six children were known to be in the house, police fired more than 10,000 rounds of ammunition, used tear gas and sprayed 1,000 gallons of water per minute at the house to try to knock it down. When all that failed, a police helicopter dropped two satchels with bombs containing military grade C-4, supplied by the FBI, on the roof of the house, igniting a fire.

Firefighters were then ordered to turn off their hoses and the inferno was allowed to engulf the house. In the film, one neighbor states, “This is war. I’ve never seen it, but I lived through it today.” Harvey Clark, a Black news reporter, is heard saying, “It’s like Vietnam out there.”

“Let the Fire Burn” reminds its audience that city officials, with full knowledge that children were in the house, chose not to extinguish the blaze. Wilson Goode, then Philadelphia’s mayor, admits during testimony before a commission that “there was a decision to let the fire burn.”

Within an hour after the bomb was dropped, the fire developed into a six-alarm conflagration that killed six adults and five children and destroyed 61 houses, leaving 250 people homeless.

The only adult MOVE member to survive the fire, Ramona Africa, was on hand for the film showing. Birdie Africa, aka Michael Ward, who was 13 when he survived the fire, died in September of this year.

Osder commented that the Philadelphia audience was “unique in that people present do know the history. Many don’t agree with the view that ‘We should sweep this under the rug.’” He called for a moment of silence for Ward.

City officials ‘negligent,’ yet no charges filed

Much of the footage in the documentary is taken from the Philadelphia Special Investigation Commission, commonly referred to as the MOVE Commission. It was appointed by Goode effectively to whitewash the murder of the MOVE members and the destruction of an African-American neighborhood.

In scenes from the hearings, the total callousness and disregard for human life by city officials and police stand out. Ed Rendell, then a district attorney who later became Pennsylvania governor, admits knowing that children were in the house and that he was aware of the danger in using this type of bomb.

Fire Commissioner William Richmond testifies that “Police Commissioner Gregore Sambor said, ‘Let the bunker burn.’” When the fire had totally engulfed the house, Goode ordered it to be put out, but Richmond claims, “I had no knowledge of that order.”

Police involved in the 1978 raid were part of the assault in 1985, assigned to an alley that was the only escape route. One of them, Officer Terrance Mulvihill, tells the commission, “We went to the back alley with machine guns to prevent the escape of MOVE members.”

In his testimony, Birdie Africa describes MOVE adults yelling that “kids are coming out.” He speaks of witnessing Conrad Africa trying to carry one of the children out on his back, only to be forced to retreat by automatic weapons fire.

The MOVE Commission found city officials to be negligent in their duties, yet no charges were filed against any of them. Two subsequent grand juries investigated the commission’s finding that the deaths of the five children were unjustified homicides, but refused to press charges. Ramona Africa, however, was charged with riot and spent seven years in prison.

During the discussion after the film, Africa said, “The warrant used to back up this murderous and destructive assault accused us of possession of explosives, arson, and risking and causing a catastrophe. All these charges were dismissed. They had no legal basis to come out there.”

She stated, “We will never stop grieving for the people murdered that day, but this system can’t give them back to us. We have turned our grief into energy to free our family unlawfully locked up for 35 years. We put our energy into pushing the system to do the right thing.”

Africa is rising, the days of colonialism are finished: This is the call being echoed…

Several immigrant groups and their supporters rallied outside the federal courthouse in Philadelphia on May…

Thousands of construction workers and teachers in at least seven provinces throughout Panamá took to…

El imperialismo estadounidense sufrió su segunda derrota histórica el 30 de abril de 1975 a…

As part of Workers World newspaper’s coverage marking the 50th anniversary of the liberation of…

From the PFLP Central Media Office The following statement from the Popular Front for the…