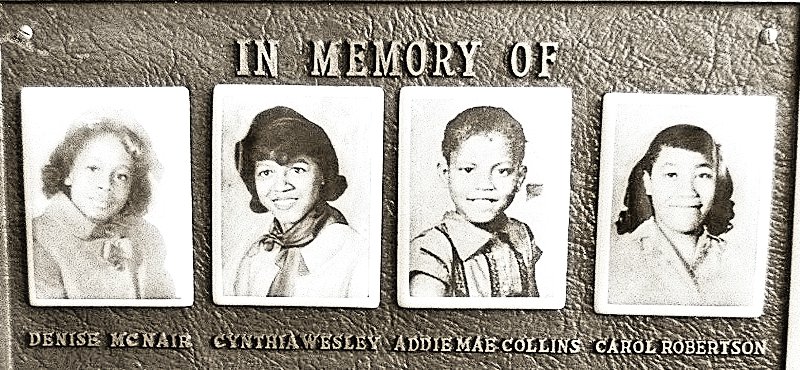

The four girls — one of whom was 11 years old and the other three all 14 — were in the church basement when 12 sticks of dynamite were ignited and unleashed upon them and other unarmed churchgoers. Offices in the church’s east rear wing were completely destroyed. A gaping hole was blown into the church’s northeastern corner frame. Records indicate that up to 23 people were injured in the explosion. Surviving church members found the girls beneath a pile of fragmented cement, shattered glass and brick debris.

This bombing was bigger than four girls. It was bigger than local minister and activist, Fred Shuttlesworth and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. It was a vicious attack upon humanity, against the innocence of what it means to be a child without worry.

It was a murderous assault on the backs of the people and their struggle for equal rights; an onslaught against peace and a nonviolent movement. Collins, McNair, Robertson and Wesley became the Civil Rights Movement’s youngest known casualties of the war for freedom and justice — four deaths that still speak volumes to the devaluation of African-American life in the United States. The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing wasn’t just an act of racism. It was the culmination of white supremacy and U.S. government complacency.

The 16th Street Baptist Church was more than just the site of a historic bombing. It was the local activist headquarters for liberty and justice, the home base for freedom fighting and grassroots organizing. It was the local symbol of hope against oppression. Racists thought that such a heinous act would work to defeat the energy of the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham, attempting to brew fear and intimidation.

Instead, such a display of brutal racism ignited a new zeal among organizers, supporters and protesters nationwide — such sheer disregard for humanity challenged the morality of even staunch moderates.

In laying out this tragic event, it is important that we understand the historical developments here; that we flush out the mitigating factors that created such an environment to begin with.

The sordid history of ‘Bombingham’

Unfortunately African Americans were already living in hell before the loss of those four little girls. The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing was no far-fetched anomaly. Such a reign of violence was no isolated case. Nicknamed “Bombingham,” Birmingham had been the home of over 50 bombings directed toward African Americans since World War II. The city’s Black working-class community was targeted with so many explosives, local residents began calling it “Dynamite Hill.” Eleven days prior to Sept. 15, the home of civil rights attorney Arthur Shores was bombed.

In 1963, dogs and water hoses were being used against defenseless human beings, including children, all over the South, but especially in Birmingham. Jim Crow’s “separate but equal” doctrine was interwoven within the fabric of social life. Sticks of dynamite were part of the landscape. Police officers were part-time law enforcers and full-time klansmen. Birmingham’s commissioner of public safety, the notorious Eugene “Bull” Connors, was a prime example. However, Birmingham was changing drastically. Black folks were demanding to vote and to exercise their right to participate in local and state politics. Rallies, protests and demonstrations were sprouting up left and right. Young people were joining the picket lines, taking critical stances and being jailed in massive numbers. Just five days before the church bombing, the order for desegregation had come down from the federal government.

Considering the degree to which Alabama Gov. George Wallace was against integration, President John F. Kennedy was reluctantly resorting to federal authority to enforce such an order. As progressive change pressed forward, the struggle could not be held back.

Lost in the shuffle were the deaths of two additional Black youth during the evening of Sept. 15, 1963. Johnny Robinson, a 16-year-old, was fatally shot in the back by a police officer. Robinson was allegedly throwing rocks at white youth who were driving through his neighborhood bearing confederate flags. Thirteen-year-old Virgil Wade was shot and killed while riding his bicycle home amidst the chaos. Multiple fires were set ablaze throughout the city that night. A bomb from an unknown source was tossed into a neighborhood grocery store. Anger, tension and frustration spilled over. An uprising had ignited. Masses crying for justice and equality poured into the streets by the thousands. National Guardsmen, numbering 500, along with 300 state troopers, were called in to “restore peace.”

When the brutal attack against four innocent churchgoers hit the world stage, it revealed the true nature of U.S. democracy; the brutal truth of what it means to be “Black in America.” The news clips of Birmingham showing the four bodies being brought out of the church shocked the world: it was live coverage of bombs and state sponsored brutality that enlightened the globe about the conditions of oppressed people in the U.S.

People in Africa, Asia and Latin America saw this on the front page of their newspapers. And as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. so carefully noted, “They aren’t going to respect the United States of America if she deprives men and women of the basic rights of life because of their skin.” It was obvious that while democracy was favorably broadcast abroad, hate was the state’s primary mandate back home, at least for the lives of African Americans.

Pursuing delayed justice

It would take 14 years and the election of a new Alabama attorney general, Bill Baxley, to bring forth even the slightest iota of justice. Up until November 1977, klansman Robert Chambliss had received a mere $100 fine and a six-month sentence at the county jail for simple possession of dynamite, 122 sticks to be exact.

Due to the efforts of Baxley and local activists, Dynamite Bob was finally tried and convicted of first degree murder of the four girls. He would go on to serve eight years until his death in 1985. When the initial bombing occurred, an eyewitness had identified Chambliss as the perpetrator who had indeed placed multiple sticks of dynamite under the church’s outside steps. However, “thanks” to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, no federal charges were filed against Chambliss.

Fact is, the FBI had evidence but chose to conceal it from state and federal prosecutors, although Chambliss was responsible for several bombings previous to the 16th Street Baptist Church explosion. “Dynamite” Bob’s activities were well known. State and city officials knew exactly who he was and condoned his rash of bombings. Along with Chambliss, there were three additional offenders who joined in bombing the church: Bobby Cherry, Herman Cash and Thomas Blanton. Blanton and Thomas would not be indicted until decades later — both surrendering to murder charges in May of 2000. Cash died in 1994 without ever serving time.

Struggle makes us stronger

I visited the 16th Street Baptist Church in March of 2009 on the Martin Luther King Jr. “Freedom Tour.” I was in that basement. I sat in the pews right next to where the bomb exploded. You could still hear the call of untimely death. You could still smell the rank of injustice looming through the air. That congregation never forgot those girls and neither should we. In 1963, their deaths were the catalyst of a new zeal of struggle. Fifty years have passed and their fire for freedom still burns.

The bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church isn’t just some sad story marked by 50 years of remembrance. For many African Americans, this story is still being told. This past Sept. 12, 50 years after the bombing heard around the world, all four girls who died were awarded congressional gold medals by President Obama. Viewed by some as an honorable gesture, gold medals don’t equal justice, especially now when the same brand of systematic racist injustice is still wreaking havoc today.

As many people already know, the 1960s were not the end of racism in the U.S. Quite often, Black and Brown youth are still the victims of racist killings, most of them by police officers. Lynchings have become weekly executions conducted by law enforcement officers. Black men are no longer hanging from Georgia pine trees. Today, the “strange fruit” that bears that peculiar stench hangs metaphorically in state prisons and jails.

The most important element here is not just to remember, but to allow remembrance to guide our actions and future deeds. As freedom fighters, we don’t have time to wallow in sorrow. Of course, our emotions bring sadness and heavy hearts when thinking of the four African-American girls, but that which brings pain must be used to fuel the good fight. This piece of tragic U.S history has only made us stronger.

Lamont Lilly is a contributing editor with the Triangle Free Press, human rights delegate with Witness for Peace and organizer with Workers World Party. He resides in Durham, N.C.

By Alireza Salehi The following commentary first appeared on the Iranian-based Press TV at tinyurl.com/53hdhskk.…

This is Part Two of a series based on a talk given at a national…

Educators for Palestine released the following news release on July 19, 2025. Washington, D.C. Educators…

On July 17, a court in France ordered the release of Georges Abdallah, a Lebanese…

The following are highlights from a speech given by Yemen’s Ansarallah Commander Sayyed Abdul-Malik Badr…

Panamá Beluche is a sociologist, professor and anti-imperialist organizer in Panamá, writing here about the…