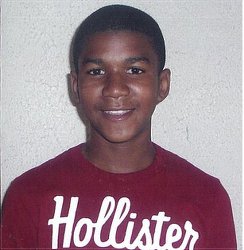

Trayvon Martin

Ho Chi Minh, anti-colonial leader of the Vietnamese people, states in the opening paragraph of his 1924 powerful essay, “Lynchings”: “It is well known that the Black race is the most oppressed and the most exploited of the human family. It is well known that the spread of capitalism and the discovery of the New World had as an immediate result the rebirth of slavery, which was for centuries a scourge for the Negroes and a bitter disgrace for mankind.

“What everyone does not perhaps know is that after sixty-five years of so-called emancipation, American Negroes still endure atrocious moral and material sufferings, of which the most cruel and horrible is the custom of lynching.” (“Ho Chi Minh on Revolution, Selected Writings, 1920-66,” Bernard B. Fall ed., Santa Barbara, Calif.: Praeger, 1967, p. 51)

Thousands of African Americans were lynched, mainly in the Deep South, following the demise of Black Reconstruction in 1877 through the height of the Civil Rights Movement. The identities of the vast majority of those lynched by white supremacists were unknown. But lynchings of mainly ordinary people still take place today.

This was certainly true of Trayvon Martin, the 17-year-old unarmed youth, who was stalked and then fatally shot by George Zimmerman in 2012 because of the color of his skin. The circumstances leading to Zimmerman’s acquittal were both a travesty of justice and a gigantic wake-up call focused on the increasing racist war in all forms against youth of color. More and more people are organizing resistance to stop these atrocities, like the Dream Defenders who are sitting-in at the Florida State Capitol in Tallahassee.

The killing of Trayvon Martin and what has happened in its aftermath are reminiscent of another lynching that happened 58 years ago — a lynching that remains a deeply, painful reminder that the legacy of racism is still thriving today. That was the heinous lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955.

Just as Trayvon’s death is triggering a new movement for social change, Till’s murder has been attributed by many as the main spark for the launching of the modern-day Civil Rights Movement, starting with the Montgomery Bus Boycott, four months after his death.

Till had traveled from his home in Chicago to visit an uncle in Money, Miss., where he was kidnapped, tortured and killed on Aug. 28, 1955. His so-called crime was allegedly whistling at a white woman in a grocery store. The woman’s spouse was KKK member, Roy Bryant, who along with his half- brother, J. W. Milam, orchestrated the murder of Till with the aid of others.

“He did what he had to do”

Bryant and Milam stood trial for Till’s kidnapping and murder before an racist, all-white jury in 1955.

For anyone, especially African Americans, to speak out against the KKK, was tantamount to signing one’s own death warrant, especially in Mississippi. But this real threat to his life didn’t stop Willie Reed, a k a Willie Louis, from walking past a menacing phalanx of Klansmen to testify at the trial and to tell the world what he saw and heard on Aug. 28.

The then-18-year-old Reed, who was a sharecropper living in Greenville, Miss., had seen Till in the back of a truck with Bryant, Milam and others.

Reed saw them take Till into a barn and then heard him repeatedly being whipped and crying out in agony. When Milam saw Reed outside the barn, he pulled out a gun and threatened to shoot him if he told anyone what he saw. Eventually, the Klansmen shot Till in the head and tossed him into the Tallahatchie River, with a cotton gin fan wrapped around his neck with barbed wire.

More than 50,000 outraged people attended Till’s funeral in Chicago. At the request of his mother, Mamie Till Bradley, an open casket revealed her son’s horribly disfigured face.

Willie Reed, who recently died at the age of 76, was forced to flee the state and change his last name to Louis following his testimony and the subsequent acquittal of the Klansmen. He was smuggled out of Mississippi, with the assistance of T. R. M. Howard, an African-American doctor and Civil Rights activist, to Chicago where he lived until his death in nearby Oak Lawn, Ill.

Both Bryant and Milam bragged about lynching Till in a 1956 Life magazine interview.

Filmmaker Stanley Nelson, who interviewed Reed for his 2003 PBS documentary, “The Murder of Emmett Till,” stated after his death, “Willie Reed stood up, and with incredible bravery pointed out the people who had taken and murdered Emmett Till. He was from Mississippi, and somewhere in his heart of hearts he had to know that these people would not be convicted. But he did what he had to do.” (New York Times, July 24)

‘Never forget the lesson taught by Willie Reed’

During a TV interview for “60 Minutes” on why he decided to testify, Reed explained, “I couldn’t have walked away from that. Emmett was 14, probably had never been to Mississippi in his life, and he come to visit his grandfather and they killed him. I mean, that’s not right.” (CBS News, July 24)

David T. Beito, a historian at the University of Alabama, said of Reed in the same Times article, “I don’t want to diminish the role played by the other witnesses, but his act in some sense was the bravest act of them all. He had nothing to gain: he had no family ties to Emmett Till; he didn’t know him. He was this 18-year-old kid who goes into this very hostile atmosphere.”

Juliet Louis, Reed’s spouse, reported that he had recurring nightmares about Till’s murder for many years.

No one should ever forget the lesson taught by Willie (Louis) Reed, a teenage sharecropper, living in the midst of fascistic-like terror, who risked his life to stand up for justice for Emmett Till, as many are doing now for Trayvon Martin.

Eight years to the day after Till’s lynching, a quarter of a million people marched and rallied in Washington, D.C., for Jobs and Freedom led by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963.

On Aug. 28, the People’s Power Assemblies Movement is calling for Justice for Trayvon Martin Assemblies. For many reasons, Trayvon Martin should be viewed as the new Emmett Till — as the inspiration for the new movement that is in birth.

The following updated article was originally posted on April 3, 2024. This April 4 will…

Boston Protesters gathered outside the Roxbury Crossing T-Station near the Islamic Society of Boston Cultural…

Over 175 people demonstrated in Philadelphia on March 31, taking to the streets from 30th…

Download the PDF. Download B&W version. Don't buy cars from Nazis Tesla 'smells like fascism'…

Portland, Oregon Fifteen groups endorsed the rally and march in Portland, Oregon, on March 30,…

Hundreds of people — including the marching band BABAM (the Boston Area Brigade of Activist…