Texas executes man with limited mental ability

The state of Texas legally lynched Marvin Wilson on the evening of Aug. 7.

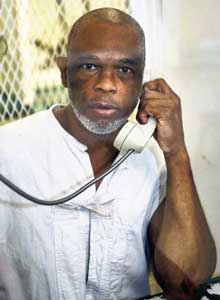

Houston, Aug. 7 — Marvin Wilson was often teased as a child in Beaumont, Texas, for being illiterate. In a recent interview on death row, Wilson said, “People, when they see that you is stupid, dumb and ignorant, they rather make fun of it and laugh about it, make you the laugh of the town, rather than say man needs some help. I spent my life fighting trying to defend my honor rather than trying to learn.” (Houston Chronicle, Aug. 7)

Today at 6 p.m., Texas plans to strap 54-year-old Wilson to a gurney and inject him with a lethal dose of Pentobarbital until he is pronounced dead.

Texas will legally lynch this African-American man who was in special education during his school years; failed several grades; was “socially promoted” to the next grade level until he dropped out in the 10th grade; and sucked his thumb well into adulthood. According to Texas, he is not mentally disabled enough to be exempt from execution.

According to the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, “Intellectual disability is characterized by significant limitations both in intellectual functioning and in adaptive behavior, which covers many everyday social and practical skills. … One criterion to measure intellectual functioning is an IQ test. Generally, an IQ test score of around 70 or as high as 75 indicates a limitation in intellectual functioning.”

Marvin Wilson scored a 61 on the standard Wechsler IQ test, a score well below the legal marker for mental disability.

In 2002, the Supreme Court established a national consensus against executing people with mental disabilities when it ruled in Atkins v. Virginia that “the mentally retarded should be categorically excluded from execution.” The court said that states must use professional standards to determine to whom this would apply.

Why is Marvin Wilson being

legally lynched?

So why is Wilson’s execution being allowed to proceed by Texas state and federal courts, as well as by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit?

After the 2002 decision, Texas developed its own standards for mentally disability, ignoring the specifications in the Atkins case. Rather than rely on scientific, clinical standards approved by the AAIDD, Texas uses seven criteria called “Briseño factors” that it devised on its own and that are not used by any other state.

These nonclinical factors, which are named after another Texas death-row case, are supposed to prove whether a defendant presents a “level and degree of mental retardation at which a consensus of Texas citizens would agree that a person should be exempted from the death penalty.” The Nation reports, “As an example, the Briseño court cited the fictitious character of Lennie Small, the mentally impaired migrant worker from John Steinbeck’s novel, ‘Of Mice and Men.’ (‘Most Texas citizens might agree that Steinbeck’s Lennie should, by virtue of his lack of reasoning ability and adaptive skills, be exempt’ from execution, the court concluded.)” (Aug. 6)

The AAIDD says that Texas’ “impressionistic ‘test’ directs fact-finders to use ‘factors’ that are based on false stereotypes about mental retardation that effectively exclude all but the most severely incapacitated.” (The Guardian [Britain], Aug. 5)

According to Wilson’s lead attorney, University of Maryland law professor Lee Kovarsky, “They said that Marvin was not retarded because he was able to work construction and get married and have a child. They said he lied in his own self interest because he denied his own guilt. How far outside scientific consensus can you go?” (TheGrio.com, Aug. 1)

Kovarsky wrote in an appeal presented to the Supreme Court that if Texas proceeds with Wilson’s scheduled execution, he “will own the grisly distinction” of becoming the lowest-IQ Texas prisoner put to death despite the Atkins v. Virginia ruling.

How can Texas allow this execution

to take place?

According to a New York Times editorial, “The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals in a 2004 ruling perversely read [the Atkins] directive to mean that the state could devise its own restricted test for retardation. It bluntly rejected the Supreme Court’s ‘categorical rule making such offenders ineligible for the death penalty.’ It defiantly refused to recognize ‘a “mental retardation” bright-line exemption’ even for those who ‘legitimately qualify’ as mentally retarded for other purposes.” (Aug. 3)

The Times noted that the Texas court’s 2004 ruling has been the basis for the rejection of mental disability claims in at least 10 other death penalty cases.

“Apparently you have to be pretty dumb in Texas not to be considered normal,” Casey Davis, a 91-year-old member of the Texas Death Penalty Abolition Movement and long-time educator and school psychologist, told Workers World. Another activist, Joanne Gavin, said, “Texas should stop ALL executions. Minus that, it must not be allowed to [disregard] the law. The Supreme Court must step in or else its Atkins ruling is not worth the paper it is printed on.”

According to reporter Ed Pilkington writing in the Guardian, Wilson’s case and the case of Warren Hill — whose execution in Georgia was called off barely 90 minutes before it was to occur last month — show that the Supreme Court has a growing problem on its hands as states act in “close to open defiance of the will of the highest judicial panel in the land in relation to the execution of people with learning difficulties.” (Aug. 5)

Activists will be at Huntsville death row, where Wilson sits imprisoned, to press the Supreme Court for justice today. Since Texas Gov. Rick Perry, who is responsible for 244 of Texas’ 483 executions, historically opts for cruel and unusual punishment, it is now up to the Supreme Court to determine if Wilson’s life will be spared.