Eyes on North Carolina: Slave rebellions & the legacy of resistance

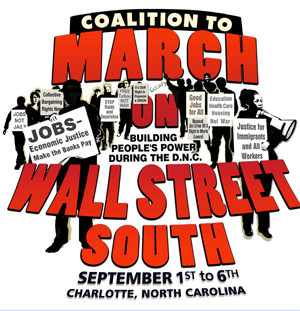

This is the third in a series of historical articles leading up to the Sept. 2 March on Wall Street South in Charlotte, N.C., during the Democratic National Convention.

Raleigh, N.C. – Most history books used in U.S. schools portray enslaved African people brought to North America as passive victims of an immoral outrage, one which is long in the past. Sure, it was terrible, the textbooks say, but Abraham Lincoln put an end to all that. That is only a tiny part of the truth, however.

The slave trade of Africans was one of the greatest crimes against humanity in all of history, killing 100 million people and underdeveloping Africa — the effects of which are apparent to the present day. The colossal amount of labor stolen from all those enslaved people laid the basis for modern capitalism and global white supremacy.

But the legacy of slavery continues to this day, with African-descended people in the United States suffering severe oppression. For instance, more Black men are in prison or on probation today than were enslaved in 1850. (Michelle Alexander, “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness”)

What is often left out of the narrative about enslaved Africans in North America, partcularly in the U.S., is the inspiring legacy of resistance they left behind. Far from being passive victims, the Africans who were attacked by the slave traders fought tooth and nail along every step of the slave trade. The consistent and determined efforts to fight back against this inhuman institution are well documented — from the time bands of mercenary traders were driven from African communities to resistance in the processing dungeons on the West Coast of Africa, the terribly overcrowded slave ships, the markets in the Americas and the plantations where Africans were forced to work.

This massive resistance of the enslaved Africans was met by unimaginable cruelty and brutality, resulting in an astronomical number of deaths at the hands of slave traders and slave owners.

When rebellions of enslaved people are mentioned in U.S. classrooms, they are characterized as violent, uncommon and isolated. These forceful fightbacks are contrasted to the “peaceful” Underground Railroad, which is held in higher esteem.

It’s important to note: The peaceful characterization of the Underground Railroad is also a half-truth. Those who escaped slavery in this way were often forced into violent confrontations with bounty hunters and the like. Harriet Tubman always travelled armed, engaged in many skirmishes throughout her career as a freedom fighter, and even recruited people to aid in one of the most famous anti-slavery revolts, John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry.

Herbert Aptheker, in his groundbreaking book “American Negro Slave Revolts,” documented more than 250 uprisings in the U.S. South that involved 10 or more slaves. These rebellions were neither uncommon nor isolated, but the unavoidable result of the intense oppression and exploitation enslaved Africans were made to endure.

These revolts were righteous resistance on the part of oppressed people. All progressives should raise up these historic acts of self-determination by enslaved Africans.

Many uprisings in North Carolina

Aptheker’s classic work was the first to bring to light the scope of these acts of resistance, including many rebellions that took place in North Carolina and the bloody repression that followed.

In 1830, wrote Aptheker, “the North Carolina legislature was secretly convened in order to devise means to suppress the dangerous disaffection of the [Black] population.” The slave masters had plenty of reason to worry. The natural tendencies of the oppressed to resist led to extensive organizing among the enslaved people. As in the Caribbean, so-called Maroon (short form of the Spanish word “cimaroon” meaning “runaway”) communities of escaped slaves were set up in the state. A runaway slave community was found in Cabarrus County in 1811. Gates County was the scene of Maroon activity in 1820. The following year Maroons were active in Onslow, Carteret and Bladen Counties, where it took 300 militia members to hunt down them.

The slave masters were vicious in their retribution. In 1805, slaves in three North Carolina counties allegedly formed a conspiracy to poison their masters. The slave masters responded by burning to death a Black woman. Three or four other African Americans were hanged.

To put these events in a global context, the slave owners in the U.S. South were desperately afraid of slave resistance following the victorious Haitian Revolution of 1791-1804,which ended slavery, kicked out the French colonialists and founded the Haitian republic.

Resistance against brutal oppression is the right of the oppressed. It’s not up to people on the sidelines to judge the tactics that the oppressed use — whether they be enslaved Africans in 1800s-era United States, Palestinians under threat of being “ethnically cleansed” out of their ancestral lands by U.S.-allied Israeli armed forces, or Colombian rebels like the FARC fighting against one of the most viciously pro-imperialist governments in South America.

It’s the duty of those not enduring that particular oppression, whatever it may be, to unconditionally uplift and support the struggles of the oppressed — against slavery, against capitalist exploitation and against imperialism.