African liberation struggles drove Portugal’s April 1974 Revolution

It was April of 1974. A popular folk song serving as a secret signal to the captains in Portugal’s Armed Forces Movement (MFA) played on Lisbon’s Radio Renascença. Units of the army in and near Lisbon had been scheduled to go out for ordinary maneuvers. Now everything changed.

It was April of 1974. A popular folk song serving as a secret signal to the captains in Portugal’s Armed Forces Movement (MFA) played on Lisbon’s Radio Renascença. Units of the army in and near Lisbon had been scheduled to go out for ordinary maneuvers. Now everything changed.

Spurred on by the growing war weariness of their troops, the growing weakness of the police-state regime, the inability of Portugal to win the war against the liberation movements in its African colonies and the growing international isolation of Portugal, the captains acted.

They had kept their plans secret from the soldiers they commanded. With troops already in their trucks, they read the new orders: Seize the capital, arrest the government and throw out the fascist gang ruling Portugal. The rank-and-file soldiers, surprised but ecstatic, carried out the new orders, hoping this action might end the wars in Portugal’s African colonies.

Each blow struck by the liberation fighters in Africa had weakened the fascist regime in Lisbon. Each strike by Portuguese workers or desertion by Portuguese soldiers boosted the revolutions in the colonies.

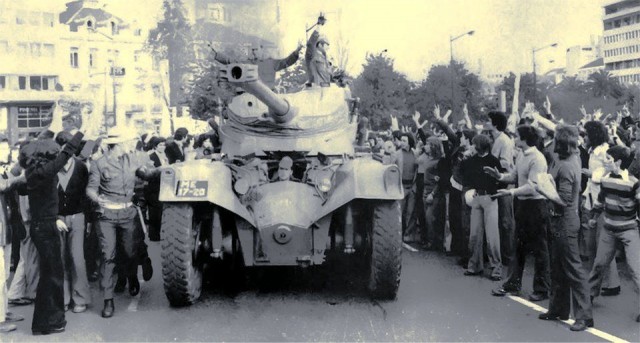

In Portugal itself, a revolt in the armed forces facilitated overturning the regime. On April 25, 1974, the Armed Forces Movement quickly ended the 48-year-old fascist police state. Still influenced by old habits of respect for power, however, the Portuguese captains politely arrested President Marcelo Caetano and the rest of the top government leaders and later exiled them to Brazil.

They replaced the Caetano gang with a military junta led by Gen. António de Spínola. This officer differed with other fascist generals only because he believed the war was unwinnable. Spínola urged Portugal’s rulers to instead work out a neocolonial relationship with the African colonies, much as French imperialism had done in West Africa.

Despite this deceptively mild beginning, April 25 was no simple replacement of the palace guard. Emboldened by the coup, masses of workers took over the streets, cheered the soldiers and for the next 18 months pressed the revolution forward.

Television news in the days following April 25 showed groups of workers surrounding and roughing up some individuals. Workers and revolutionaries recognized their former torturers from the notorious PIDE, the Portuguese political police, and dispensed justice.

Defying Spínola’s commands to leave the prisoners in the jails, the crowds, with the support of the troops, emptied the prisons of revolutionaries and anti-fascists while putting the PIDE thugs behind bars. By May Day — six days later — hundreds of members of the Portuguese Communist Party and other revolutionary groups were out of prison or back from exile to organize and agitate in the factories, farms and streets in Portugal.

African liberation movement

The armed struggles in Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau/Cape Verde and Angola seeking liberation from Portuguese colonialism had undermined the army and made the April 25 Revolution possible. The African battles had opened on Feb. 4, 1961, when Angolan freedom fighters stormed a prison to free their comrades. As the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola sang in its hymn, “The heroes broke the chains.”

One of the great African Marxists, Amílcar Cabral, was the leader of the liberation struggle in Guinea-Bissau/Cape Verde, Portugal’s smallest African colony. Cabral organized a popular army to fight for the freedom of a million people; in a dozen years of people’s war, this army had liberated large parts of this small territory and set up a new government.

Despite his other priorities organizing a people’s war, Cabral knew how important it was to reach out to the soldiers in the colonial army. His organization, the African People’s Independence Party of Guinea and Cape Verde, even as they fought the Portuguese, arms in hand, also made an appeal to the draftees. In a 1963 leaflet, Cabral made it clear the liberation forces would win, and those opposing liberation might well die, but he added:

“Be courageous, refuse to fight our people! Follow the example of your courageous comrades who refused to fight on our land, who revolted against the criminal orders of your leaders, who cooperate with our party or who abandoned the colonial army and found in our midst the best reception and fraternal aid.”*

In a blow that robbed the world’s oppressed peoples and workers of a great leader, PIDE agents assassinated Cabral in Conakry, Guinea, in 1973. But even this setback failed to stop the liberation struggle. From tiny Guinea-Bissau/Cape Verde, as well as in much larger Angola and Mozambique, the liberation struggles left their mark on Portugal’s army. And the Armed Forces Movement brought the war home.

Soldier resistance develops

In a report to the PCP Central Committee in April 1964, PCP Secretary Gen. Álvaro Cunhal described how the liberation war of the colonial people interacted with the struggle against fascism inside Portugal:

“The resistance of the soldiers against the colonial war is not only one of the most brilliant examples of solidarity of the Portuguese people with the colonial peoples. It is also a new element in the struggle against the fascist dictatorship, an index of the weakened state of the fascist state apparatus, of the radicalization of the politics of the popular masses and the combat readiness of the youth. …

“The Angola war gave new reasons for the development and generalization of the struggle of the soldiers. Given the fascist discipline and the political spying that existed in the armed forces, even if only a half dozen mass actions had taken place against the fascist policies, this would have been enough to represent a strong sign of resistance of the people and the youth to the fascist policies and the colonial war. But it wasn’t only a half dozen. In the last three years [before 1964], hundreds of struggles of the soldiers have taken place.

“There was also resistance to being sent to the colonies, including work stoppages in the military quarters and barracks, on ships and military hospitals. … Desertions reached a significant volume. …

“Sometimes the insubordinations were accompanied by small acts of violence. The soldiers burned their cots or broke windows in their barracks or destroyed the furniture.

“The struggle of the Portuguese people against the colonial war reached the colonies themselves. Risking their lives, many soldiers refused to leave for the front or to participate in atrocities. Pilots refused to carry out bombings with napalm or did them off-target. Officers and soldiers organized resistance. Others deserted right on the field of battle.”

The long war forced small Portugal to triple the size of its armed forces to 210,000 troops and finally provoked the Armed Forces Movement to turn the guns around. This in turn unleashed a countrywide class struggle of workers against their exploiters inside Portugal.

Counterrevolution drives revolution

In the year following April 1974, two major confrontations between the revolutionary workers and the Spínola grouping took place, first in September 1974, when masses of workers mobilized to stop a reactionary demonstration, and then the following March. They both took the form of defense of the revolution from counterrevolutionary actions.

On March 11, 1975, Spínola, working with reactionary forces inside and outside Portugal, attempted a military coup. But again there was a rebellion of the rank-and-file troops. The coup failed when the paratroopers sent to punish revolutionary soldiers instead fraternized with and joined them.

Spínola fled Portugal for Spain. The MFA purged the most reactionary officers. The biggest advances for the workers were written into law in the months after this failed coup.

Overseas, the liberation movements continued their struggles. By Sept. 15, 1974, Guinea-Bissau/Cape Verde was independent. The following year Angola and Mozambique won their freedom from Portugal. Even East Timor, half of an island in the Indian Ocean, won a short-lived independence in November 1975, but was soon occupied by Indonesia.

In Portugal, there was reinstatement of rights to unions and nationalization of factories, banks and much of the media, plus a wide-reaching agricultural reform that gave legal rights to land seizures by agricultural workers and established collective farms. Begun by actions of workers and other collectives, nearly all these steps were codified under the governments headed by Prime Minister Vasco Gonçalves, himself a colonel and leader of the MFA. Gonçalves was promoted to general in 1975.

Faced with homegrown reaction and U.S.-NATO intervention, the Portuguese movement fell short of completing a workers’ revolution, such as had taken place in Russia in 1917. By the fall of 1975, a more rightist grouping of officers gained control of the MFA and removed progressive elements from the government. The rightists began eroding the revolutionary gains, a process that has continued until today, when the Portuguese working class faces a new crisis.

Comparison with GI resistance

Despite differences with the political situation in the United States, the Portuguese revolutionaries’ experience of organizing in the military during a colonial war had many similarities with that of the American Servicemen’s Union and among dissident GIs in general during the war against Vietnam.

In an analogous way to the Portuguese experience, the Vietnamese liberation fighters sparked revolutionary feelings among some U.S. GIs, as did the Black Liberation Movement at home. U.S. troops’ resistance during the Vietnam War from 1966 to 1973 mirrored the early forms of resistance among the Portuguese troops during the colonial wars that Cunhal described.

Also, in the 1960s and early 1970s, the Portuguese Communists had a conscious and worked-out approach to the soldiers with the goal of winning the troops to the revolutionary struggle both to sabotage the colonial war and to overthrow the fascist dictatorship.

In the U.S., Workers World Party’s goal, shared by the leading ASU organizers, was to break the chain of command in the U.S. Armed Forces so that the U.S. could neither wage imperialist war abroad nor repress workers’ struggles or rebellions in oppressed communities at home.

In 1969, some top U.S. generals requested that the U.S. raise the troop level from 540,000 to one million. Instead, the U.S. administration chose to begin withdrawing troops, relying on airpower and on building a puppet army. This strategy could not prevent an eventual Vietnamese victory, but it did decrease tensions inside the U.S. military. Lisbon’s rulers, by trying to win the wars in Africa with Portuguese troops, instead provoked the April Revolution.

*Quoted from “Collected Works of Amílcar Cabral (vol. II)/Unity and Struggle/Revolutionary Practice,” Seara Nova, Lisbon, 1977. This and the Cunhal quote, which is from “Path to Victory,” pages 191-193, are reproduced at greater length in Catalinotto’s forthcoming book, “Turn the Guns Around: Mutinies, Soldier Revolts and Revolutions.”