Helen Keller: Socialist, anti-racist, disability rights activist

Helen Keller is perhaps remembered by most people in the U.S. for one moment in her life, dramatized in the play and movie “The Miracle Worker.” Seven-year-old Helen, without sight or hearing because of an illness at 19 months, stands with arms outstretched as her teacher, Annie Sullivan, pours water over her hands and finger-spells W-A-T-E-R over and over into her palms. As consciousness of the connection between word and substance comes to her, Helen is transformed.

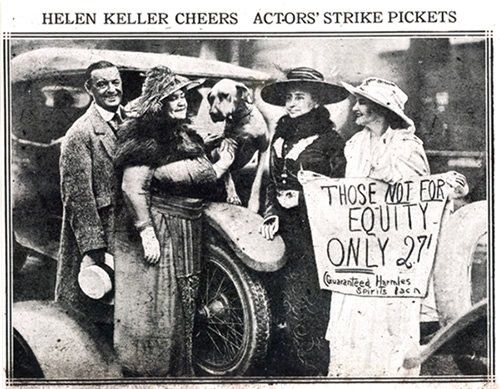

“I am a Socialist because only under socialism can everyone obtain the right to work and be happy.” – Helen Keller, in black hat, supporting actors’ strike, 1919.

That dramatic moment is typical of how Helen Keller’s complex radical life has been reduced to a stereotypical symbol of “heroic disability” and also distorted by the sexist and ableist notion that she was only a blank slate for others to write their ideas upon.

Keller was decidedly a person who thought for herself. She was born in 1880 near Tuscumbia, Ala., to a Confederate veteran — a plantation owner who had previously enslaved people of African descent. Keller was raised on the farm during the violently racist post-Reconstruction era when Southern plantation owners and Northern capitalists were striking deals for de facto re-enslavement of recently freed Black people.

Yet Keller as an adult became a staunch anti-racist, an outspoken supporter of the recently founded NAACP and writer for its magazine, “The Crisis.” She demonstrated through the 1950s, into her elder years, in anti-segregation protests and rallies. (“Helen Keller: Selected Writings,” 2005)

Her growth as a thinker and activist was no miracle. It was rooted in her access to the extensive political library of Annie Sullivan’s socialist spouse, John Macy. By 1908, after her graduation from college, Keller was reading Marx, Engels, socialist publications and Marxist economics, often in German Braille. (tinyurl.com/ntwp4gd)

Keller called Rockefeller a ‘monster of capitalism’

In 1909 Keller joined the American Socialist Party and campaigned for its candidates, including Eugene Debs, the SP leader who ran for U.S. president from his prison cell in 1920. She supported striking workers, including those murdered in 1914 in the Colorado Ludlow Massacre by hired mercenaries, and called owner John D. Rockefeller a “monster of capitalism.” She defined herself as a “militant suffragist,” campaigning for women’s right to vote because she believed this was linked to the struggle for socialism. (D. Hermann, “Helen Keller,” 1999)

Throughout her life, Keller continued to be a dedicated socialist, over time shifting her focus to the mass-based Industrial Workers of the World after becoming dissatisfied with the SP’s electoral tactics. She celebrated the triumph of the Bolsheviks in the Russian Revolution, named Vladimir Lenin one of the three greatest men of her era and regularly wrote articles for Communist Party newspapers and journals. (tinyurl.com/h6dt7y4)

Keller identified her Marxist analysis and her socialism as deeply interconnected with her disability activism. As she studied economics, she visited factories and felt the very vibrations of the brutal industrial conditions that resulted in worker injuries. She concluded that the main causes of disability in the U.S. were industrial and workplace accidents and sickness from owners placing profits above worker safety.

In her writing Keller indicted capitalism for causing most disabilities and for amplifying the misery of disabled people through increased poverty and isolation. Her 1913 “Out of the Dark: Essays, Letters, and Addresses on Physical and Social Vision” articulated this analysis. Other political writings included “Social Causes of Blindness” (1911) and “The Unemployed” (1911).

Contemporary critics lambasted Keller for her socialism. In a 1924 letter to social reformer U.S. Sen. Robert La Folette, she replied: “So long as I confine my activities to social service and the blind, they compliment me extravagantly, calling me ‘arch priestess of the sightless,’ ‘wonder woman,’ and a ‘modern miracle.’ But when it comes to a discussion of poverty, and I maintain that it is the result of wrong economics — that the industrial system under which we live is at the root of much of the physical deafness and blindness in the world — that is a different matter!”

The U. S. government took her seriously. By the time Keller died in 1968 at 87, the FBI had kept her under surveillance for most of her adult life.

In Women’s History Month, let us honor Helen Keller for her anti-racist, disability rights activism — and her socialism. At the height of McCarthy anti-communism, she affirmed in an interview that she was still a socialist. She hastened to add that she still owned a copy of Marx and Engels’ “Communist Manifesto” — in Braille. (New York Times, June 25, 1950)