VERNON DAHMER: Unsung martyr of Civil Rights struggle

Vernon F. Dahmer Sr., a staunch NAACP activist and a close friend of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was killed on Jan. 10, 1966, in a Ku Klux Klan terrorist raid on his home at Kelley Settlement in Hattiesburg, Miss.

Vernon F. Dahmer Sr., a staunch NAACP activist and a close friend of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was killed on Jan. 10, 1966, in a Ku Klux Klan terrorist raid on his home at Kelley Settlement in Hattiesburg, Miss.

The Dahmer family had received numerous threats prior to his death. He and Ellie Dahmer, his spouse, took turns sleeping in order to guard the home. That was not enough to ward off Klan attacks that fateful morning when his small grocery store and home were invaded and firebombed at 2 a.m.

In the 1950s, Dahmer and other activists, including Medgar Evers, were victimized for establishing an NAACP Youth Chapter in Hattiesburg. The “One Person One Vote: The Legacy of SNCC and the Fight for Voting Rights” website noted that this was a bold move by the organizers: “However, when its young president, Clyde Kennard, tried to enroll at a segregated college, he was framed for a petty crime and sentenced to seven years in prison. When Kennard became seriously ill, his jailers refused to give him medical treatment. He died not long afterwards.”

Nonetheless, Dahmer continued to struggle for Civil Rights, serving as NAACP president in Hattiesburg at a time when such a public stance made one a target of the Klan and the White Citizens Council. He was a proponent of universal voting rights and pledged his life to eliminating obstacles that prevented African Americans from gaining full access to the franchise.

Civil Rights groups vs. racist state govts

Dahmer mentored SNCC organizer Joyce Ladner during her early years when he took her to political activities and demonstrations protesting legal segregation. During the late 1950s when Ladner was a teenager, she learned firsthand about the dangers of Civil Rights activism when the NAACP was outlawed in Mississippi and other Southern states.

In 1956, several Southern states initiated legal actions against the NAACP, saying the organization’s existence defied state statutes. State governments demanded the Civil Rights organization’s membership lists and financial records. If these documents had been turned over to these authorities — many of whom were Klan and White Citizens Council functionaries — then NAACP members and contributors would have faced physical and economic retaliation by the white ruling class.

By their actions, these racists aimed to force the NAACP out of existence as the African-American struggle grew in influence — as exemplified by the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the mass response to the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till. The African-American youth was killed in Money, Miss., in August 1955 while visiting from Chicago.

NAACP state chapters defiantly refused to hand over membership rolls. Consequently, huge fines were levied against them, and organizers were threatened with imprisonment. The NAACP fought these attacks all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in a landmark case titled NAACP v. Alabama.

The high court ruled in the NAACP’s favor in 1958, noting that the state’s attempt to suppress the organization by demanding its membership records violated the Constitution’s guarantee of freedom of association. Other NAACP chapters in Southern states also gained favorable court rulings. However, reactionary attacks against the NAACP and other Civil Rights groups continued into the 1960s.

Klan targeted Dahmer

Teaching for Change’s website published remarks by Ladner prepared for the 50th anniversary commemoration of Dahmer’s martyrdom, hosted by the Clarion Ledger in Jackson, Miss., on Jan. 8. She said, “In his short 58 years, Dahmer launched voter registration drives, and adhered to the philosophy that it was his responsibility to be his brother and sister’s keeper. Perhaps it was also his economic independence that made him a target for the Ku Klux Klan.”

Ladner explained that Dahmer “annexed large tracts of land, built a commercial farm of cotton, owned a saw mill, a planer mill, and a grocery store. He hired his Black neighbors from Kelley Settlement to work for him, thereby carrying out his philosophy of being a good neighbor. This was largely unheard of in the fifties and sixties because very few Black people owned businesses. The jobs he provided reduced Black flight to Northern cities and strengthened the local community. Vernon Dahmer was a generous man who believed in the power of a united community.”

The attack on Dahmer and his family was ordered by Sam Bowers, one of the most notorious KKK Grand Wizards of the period. Consumed with virulent hatred of African Americans, Bowers, like the Klan’s early founders in the late 1860s, came from an affluent family whose members were involved in business and politics.

On Jan. 10, 1966, about 10 miles outside of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, the home of Vernon Dahmer was firebombed by the KKK.

The New York Times on Nov. 6, 2006, the day after Bowers’ death, described the morning of Jan. 10, 1966, when “Mr. Bowers sent two carloads of Klansmen with 12 gallons of gasoline, white hoods, and shotguns to the Dahmer house near Hattiesburg, Miss. … The burning gasoline was tossed into the house; Mr. Dahmer, whose lungs were seared, held attackers at bay so his family could escape, then died later in the arms of his wife.”

The Times said Bowers was a “leader of the most violent and secretive division of the Ku Klux Klan, the Mississippi White Knights, which at its peak had up to 10,000 members. … The F.B.I. attributed nine murders and 300 beatings, burnings and bombings to Mr. Bowers and the group. … On Feb. 15, 1964, he coaxed 200 Klansmen assembled at Brookhaven, Miss., to join him in founding the Mississippi White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, an organization that defined itself in its unhesitating willingness to use violence.”

Four unsuccessful attempts were made to convict Bowers for Dahmer’s murder, but the fifth trial in 1998 won a conviction and life sentence. It was Ellie Dahmer and the Dahmer children who persisted in keeping the case in front of Mississippi authorities.

Bowers died in a Mississippi prison at the age of 82. Despite his death and that of other Klan leaders, racist violence remains a stark reality in the U.S. well into the 21st century.

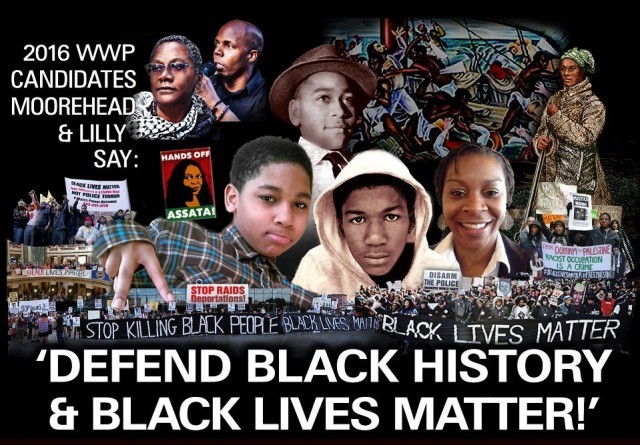

Racist killings, such as Dahmer’s, inspired SNCC leaders and others to adopt Black Power and militant self-defense as a political strategy in 1966. Five decades later there is a resurgence of anti-racist demonstrations and urban rebellions.

There is still strong resistance by law enforcement organizations, prosecutorial agencies, and local, state and federal courts to pursuing criminal cases against perpetrators of racist violence against African Americans and other oppressed peoples.

Congress never passed a federal anti-lynching law after numerous attempts during the early 1900s when mob violence against African Americans was routine, resulting in thousands of deaths and injuries. Today, neither the House of Representatives nor the Senate has taken any legislative action aimed at ending the blatant state repression against people of color communities.