What’s driving shocks to the economy

Jan. 25 — The working class in the U.S. has suffered devastating blows since the 2007 capitalist economic crisis. Now the threat of a new downturn is rumbling through the financial markets.

City and state budgets have already been cut in the name of austerity. Government services, including those in hospitals, schools, libraries, water works and maintenance, have been privatized — sold to generate immediate revenue needed to pay the interest on bank loans. The impact of these criminal policies can be seen in Flint’s poisoned water and in decaying schools, from Los Angeles to Detroit and Philadelphia.

Even as a new round of layoffs is pending, the number of people participating in the workforce has reached its lowest level in 30 years, despite population growth. Real wages, stagnant since 1979 according to an Economic Policy Institute report of Feb. 19, 2015, have not improved since then.

The workers whose labor produces all wealth have been receiving a smaller and smaller portion of the value they produce. Some 56.3 percent of the U.S. population is now living paycheck to paycheck, with less than $1,000 in checking and savings accounts combined. And 24.8 percent have under $100 in their accounts. (Forbes, Jan. 6)

Stagnant and falling wages, alongside the increasing productivity of labor, have led, under capitalism, to the concentration of extreme wealth in private hands at a scale unknown in history. The 62 richest people on earth now hold as much wealth as the poorest 3.5 billion. (Oxfam, Jan. 17) Five years ago, 388 super-rich held this criminal status. The staggering concentration of wealth continues unabated.

One-fifth of paper value wiped out

The other feature endemic to capitalism that Karl Marx explained 165 years ago is asserting itself yet again. Capitalism — the economic system built on social production but private expropriation — has never been able to solve the lurching cycles of boom and bust caused by overproduction. The overproduction of every commodity is again shaking financial markets.

The fall in the price of oil from more than $110 a barrel in June 2014 to below $30 today has received great attention. But a similar collapse has happened in industrial goods, steel, piping, sheet metal, coal, gold, aluminum, zinc and major food crops.

Since the New Year, stock markets around the world have been dropping inexorably. From New York’s Dow Jones and the S&P 500 to the main European stock exchanges in London, Paris and Berlin; to markets in Dubai, Tokyo, Hong Kong and Shanghai; together they have lost more than 20 percent of their value, entering what is called a “bear market.”

A fifth of all stock market wealth in the world has been wiped out. This may not immediately affect most workers. But the capitalists’ way of dealing with the loss of their speculative wealth is to immediately turn on workers who have less than $1,000 or $100 to their name.

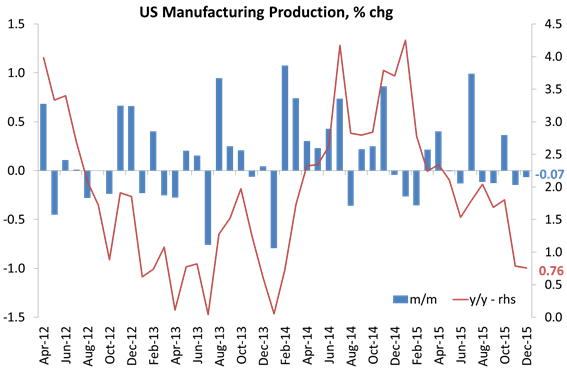

President Barack Obama’s State of the Union address highlighted a modest increase in service jobs at the lowest pay — from call centers to fast food restaurants. However, hundreds of thousands of workers in heavy industry, energy production, banking and financial services — from DuPont, Alcoa, John Deere and BP to Morgan Stanley — have already been laid off over the last year.

Bailout deepened the crisis

Capitalist economists, hesitant to use the term recession, have come up with a new term for such a long period without economic growth: “secular stagnation.” International conferences and numerous academic papers have been held on this topic. Secular stagnation is a nicely vague term that hides the reality. Capitalism, in order to expand, must find markets in which to sell its products at a profit. When it cannot do this, the entire global system goes into a spiral of crisis.

Bailouts have not succeeded in jump starting the economy. Years of almost zero interest rates to encourage giant loans supposedly to stimulate production may instead have made this capitalist downturn much worse.

A British paper quotes an official of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development: “‘The situation is worse than it was in 2007. The world faces a wave of epic debt defaults. Our macroeconomic ammunition to fight downturns is essentially all used up,’ said William White, the Swiss-based chairman of the OECD’s review committee and former chief economist of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).” (Telegraph, Jan. 19)

‘Zombie’ ships

There is overproduction in commodities, from oil to finished products like toys, clothing and cars. There is even a glut of the huge container ships that move more than 95 percent of the world’s manufactured goods.

The shipping industry is facing its worst crisis in living memory after years of rapid expansion fueled by cheap debt. The world fleet doubled in size from 2010 to 2013. (Reuters Business Insider, Jan. 20)

Competition among shipping companies has pushed the building of a new generation of super freighters that can carry 19,000 containers, compared to earlier ships that carried just 5,600. It takes years to build such ships. Orders were placed when a full global recovery was expected after 2009.

Shipping corporations that financed their fleets with 60 percent debt and 40 percent equity have seen that equity become worthless.

Now “zombie” fleets accept freight at maverick prices just to keep going. But the owners have no hope of repaying the capital on their loans. Banks are afraid to pull the plug on these loans because then they would be forced to list the losses on their books.

The Baltic Exchange, which has set shipping rates for more than two and a half centuries, says the situation its members face now is grim.

Giants felled by debt

Even giant multinational corporations that survived decades of past capitalist turmoil are now tottering. Years of almost zero interest spurred many of the world’s largest commodity corporations to take out huge debts to invest in further expansion and mergers. But now that the price of commodities has crashed to one-half or even one-third of a year ago, the market value of these corporations has gone into free fall.

One of the largest and oldest gold and copper mining corporations, Freeport McMoRan, is in crisis after taking out big loans about three years ago to buy into oil and gas. Now, with the oil glut, the company’s stock has fallen from $60 a share to below $4. Freeport McMoRan, now valued at $4.8 billion, is carrying a debt of $20 billion, so it is slashing jobs and all capital spending. But in order to meet its debt payments, it is continuing to pump oil, even at extremely depressed prices. (New York Times, Jan. 22)

In previous price slumps, commodities producers immediately cut back. But this time, due to their enormous debt, they continue to flood the market, making their situation worse.

Capitalists blame their woes on China

The global glut of all commodities is currently being blamed on a slowdown in the growth of People’s China — the world’s second-largest and most rapidly growing economy.

The chaos and ruthless competition of the capitalist system itself are never blamed. For example, both U.S. and German corporations have exacerbated conditions in China at plants that are joint ventures. A decision by Volkswagen, GM and other major automakers to rein in their production in China due to a global glut in autos meant they first canceled workers’ bonuses at their plants. “The bonuses being scrapped typically amount to more than half of the assembly-line workers’ take-home pay.” (Reuters, Sept. 15, 2015)

These international corporate giants not only cut assembly-line workers’ take-home pay, hours, break times and number of shifts, but they and other major Western firms also cut billions of dollars from major expansion plans they had in China. Of course, all these cuts in investments, announced more than three months ago, impacted on the Chinese stock market.

These abrupt cuts have spurred increasing efforts to further develop more stable links and trade among China, Russia, Latin America and Africa. A Cuban article titled “Weathering the storms of the 21st century,” written days ago, said this rapidly developing trade was mutually beneficial. By 2014, the value of bilateral trade between China and Latin America was 22 times what it had been in 2000. (Granma, Jan. 19)

How deep and intractable the coming crisis will be, or what will spark it, can’t be predicted. But the urgency for workers of sounding the alarm and organizing a determined fightback is beyond dispute.