1966 murder prompted SNCC’s anti-war stance

Samuel “Sammy” Leamon Younge Jr., a 21-year-old activist from Tuskegee, Ala., was shot and killed at a Standard Oil gas station as he was attempting to use a whites-only restroom in Macon County on Jan. 3, 1966. His racist murder occurred during the time when he was a voter registration volunteer.

Samuel “Sammy” Leamon Younge Jr., a 21-year-old activist from Tuskegee, Ala., was shot and killed at a Standard Oil gas station as he was attempting to use a whites-only restroom in Macon County on Jan. 3, 1966. His racist murder occurred during the time when he was a voter registration volunteer.

For many decades prior to the mid-1960s, African Americans were by law denied equal access to public and private accommodations in the U.S. South. It was not until the summer of 1964 that a comprehensive Civil Rights bill was passed aimed at ending the Jim Crow system of strict racial segregation.

The Voting Rights Act was signed in August 1965 by President Lyndon B. Johnson in the aftermath of the repression meted out against the people of Alabama. They were merely attempting to enforce previous legislation and the 14th and 15th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution, which ostensibly guarantees due process and the right to vote to all born and naturalized U.S. citizens.

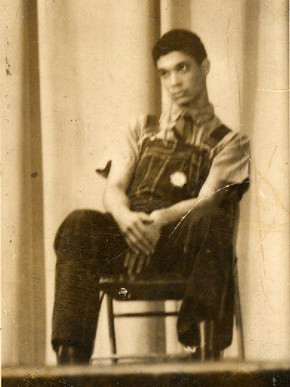

Sammy Younge: Civil Rights hero

Younge’s parents were African-American professionals connected with Tuskegee Institute and the segregated public school system.

The Black Past website reports that prior to Younge’s intervention in the Civil Rights Movement: “Between September 1957 and January 1960 Younge attended Cornwall Academy, a college preparatory school for boys in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, a town famous as the birthplace of W.E.B. DuBois. Younge graduated from Tuskegee Institute High School in 1962 and enlisted in the U.S. Navy.”

The article continues: “Soon after his enlistment Younge served on the aircraft carrier USS Independence during the Cuban Missile Crisis when the vessel participated in the United States blockade of Cuba. After a year in the Navy, Young developed a failing kidney that had to be surgically removed. He was given a medical discharge from the Navy in July 1964.”

After returning from the Navy, Younge enrolled in Tuskegee Institute and joined both the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the university-based Tuskegee Institute Advancement League, which led many campaigns in Alabama for voting rights and independent political organization in 1965.

Both SNCC and TIAL not only were engaged in voter registration efforts, but were challenging segregated facilities that proliferated even after passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts. Younge saw SNCC and TIAL as avenues of expression designed to win full equality and self-determination for African-American people. He participated in the Selma-to-Montgomery March from March 21 to 26, 1965.

After the campaign in Selma, an area where SNCC had worked since 1962, organizers spread out to neighboring Lowndes County. There, the first Black Panther organization was formed by the soon-to-be SNCC Chairman Stokely Carmichael — later known as Kwame Turé — and his comrades, working in close collaboration with local activists.

Martyrdom sparked more resistance

Sammy Younge’s murder in nearby Macon County led to a variety of protests. His death symbolized why people had to intensify the struggle to expose the false notion of “fighting for freedoms” abroad that were routinely denied in the U.S.

Student protests erupted in Tuskegee when white county officials initially declined to indict Marvin Segrest, the elderly, white gas station attendant who shot Younge. Yet, when there was a show trial in December 1966, the all-white jury, in a majority African-American county, deliberated for only one hour and 10 minutes and then acquitted Segrest.

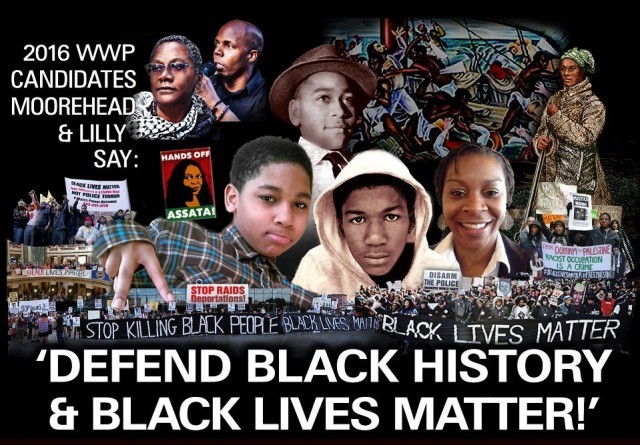

SNCC was in the process of transitioning its program to Black Power and revolutionary nationalism in 1965-66. The blatant killing of Sammy Younge Jr. prompted SNCC to issue its historic statement against the war in Vietnam three days after his murder. SNCC was the first major Civil Rights organization to do so.

SNCC’s statement reads, in part, “The murder of Samuel Younge in Tuskegee, Alabama, is no different than the murder of peasants in Vietnam. For both Younge and the Vietnamese sought and are seeking to secure the rights guaranteed them by law. In each case, the United States government bears a great part of the responsibility for these deaths.

“Samuel Younge was murdered because United States law is not being enforced. Vietnamese are murdered because the United States is pursuing an aggressive policy in violation of international law. The United States is no respecter of persons or law when such persons or laws run counter to its needs or desires.” (tinyurl.com/ZR4ornq)

The organization’s views on the war drew widespread attacks on its activists across the South. Its anti-war statement drew the ire of the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and a wide spectrum of politicians in the Democratic and Republican parties.

SNCC activist Julian Bond was elected to the Georgia Legislature in late 1965 and was slated to take office in early 1966. He was denied his seat for two years because he refused to distance himself from SNCC’s position on the war.

SNCC’s call for an end to the U.S. war against Vietnam and abolition of the draft sent shock waves through the ruling class, particularly as dozens of urban rebellions erupted during the spring and summer of 1966.

In June 1966, during the “March Against Fear” through Mississippi, SNCC Field Secretary Willie Ricks — now known as Mukasa Dada — and newly elected SNCC Chairman Carmichael advanced the slogan “Black Power.”

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., leader and co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, left the emerging Chicago Freedom Movement to march to Jackson, the state capital, alongside SNCC; Floyd McKissick, executive secretary of the Congress on Racial Equality — which had also adopted the Black Power slogan — and in solidarity with the youth and farmers of Mississippi.

Opposing the Vietnam war

The SCLC had not taken a formal position against the war even after SNCC issued its statement on Jan. 6, 1966. Nonetheless, King admitted in March and April of 1967 that he could no longer refrain from speaking out against what the Johnson administration was doing to the people of Vietnam and Washington’s failure to adequately address poverty and racism in the U.S.

On March 25, 1967, King and other anti-war activists, including Dr. Benjamin Spock, noted pediatrician and author, led a demonstration of hundreds of thousands of people in Chicago. They called for a comprehensive halt to hostilities against North Vietnam and the revolutionaries fighting for national liberation of the South. Just 10 days later, the SCLC leader delivered his historic speech, “Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam,” at Riverside Church in New York City.

A cacophony of condemnation poured in opposing King’s views on the Vietnam War. On April 15, he participated in a march from Central Park to the United Nations in New York condemning the bombing of Hanoi and calling for U.S. forces to be withdrawn from the country.

Just one year later King was assassinated in Memphis, Tenn., on April 4, 1968, while assisting a strike of African-American sanitation workers seeking recognition as a labor organization affiliated with the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. His combined efforts for Civil Rights and the elimination of poverty, along with his opposition to U.S. militarism and imperialism, sealed his fate with the ruling class.

For more information, see “Sammy Younge, Jr.: The First Black College Student to Die in the Black Liberation Movement” by James Foreman, Grove Press, 1968.