Former Black Panther killed in California prison

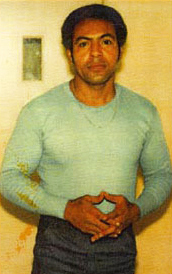

Hugo Pinell, 71, a former comrade of George L. Jackson, was killed on Aug. 12 in California State Prison-Sacramento near Sacramento, Calif.

Pinell, known by many as “Yogi Bear,” had recently been released from 46 years of solitary confinement and was the longest serving prisoner held in administrative detention in the state of California. He had written to one of his supporters that he feared for his life at the prison. (KPFA interview with Kiilu Nyasha, Aug. 13)

In 1965 Pinell was given a 3-years-to-life sentence for rape, a crime for which he said he was not guilty. He and his mother were told that if he did not confess, he could face the death penalty.

Pinell was stabbed to death by another prisoner on the first day he was released into general population at CSP-Sacramento. The corporate media described the circumstances surrounding his killing as a “riot” when clashes erupted after Pinell was brutally stabbed in the prison yard.

His death has sent shockwaves through the ranks of veteran Black Panther Party members, supporters of political prisoners and anti-racist forces.

San Quentin Six and George L. Jackson

Pinell was a member of the San Quentin Six, who were involved in the attempted prison break to liberate George Jackson on Aug. 21, 1971, where Jackson was gunned down by guards. Three prison guards and two white inmates also lost their lives in that incident. After the rebellion, six inmates were charged in their deaths: Hugo Pinell, Willie Tate, Johnny Larry Spain, David Johnson, Fleeta Drumgo and Luis Talamantez.

Long before that, George Jackson was already well known throughout the African-American revolutionary movement and the left as a whole. His prison letters were published in the 1970 book entitled “Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson.”

The Soledad Brothers were three African-American prisoners, George Jackson, Fleeta Drumgo and John Clutchette, who were charged with killing a guard at San Quentin in January 1970. Several days earlier, three Black inmates had been killed by white prison guard snipers during a racial melee in the yard.

A national movement arose in defense of the Soledad Brothers, which drew the support of Angela Davis, a Communist Party member and lecturer who had been terminated by the University of California, Los Angeles in 1969 because of her political beliefs.

Jackson had originally been sentenced to a 1-year-to-life sentence in California in 1960 for being in the company of several others who stole $70 from a gas station. During his tenure in prison, Jackson began to read voraciously about history, military science, philosophy and Marxist-Leninist theory.

Prison authorities attempted to break Jackson’s confidence and defiance for many years. He became a leader and mentor for other prisoners during a period when the Civil Rights, Black Power, anti-war and left movements were gaining tremendous ground in the U.S.

Pinell spent decades in solitary confinement for refusing to compromise with the system, and was the only one of the San Quentin Six remaining in prison. All the others had been released decades earlier.

Black August started by political prisoners

Pinell’s killing occurred during Black August, an annual commemoration of the resistance of African Americans to oppression and exploitation. Created by political prisoners years ago, Black August continues to be commemorated across the U.S.

The month-long acknowledgement of resistance stems from the historical fact that many great efforts aimed at liberation took place during August. Such historical developments include the beginning of the Haitian Revolution (1791); Nat Turner’s Rebellion in Virginia (1831); John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry (1859); the Watts Rebellion (1965); the attempt by Jonathan Jackson, the younger brother of George, to free him from prison (1970); the San Quentin Rebellion (1971); and the 2014 police murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo.

The killing of Pinell illustrates the character of national oppression, economic exploitation and political repression against African-American people. Resistance to the inhumane conditions prevailing both outside and inside prison walls is continuing today through the rebellions and mass demonstrations in Ferguson, Baltimore and other cities.

African Americans are still jobless at rates at least twice as high as whites. Millions are confined to low-wage jobs with no economic security or social benefits.

Every week news stories report that African Americans are being gunned down by police and vigilantes.

The school-to-prison pipeline is still very much in evidence in urban areas. A disproportionate number of inmates and people under judicial supervision are African Americans and Latinos/as from poor and working-class backgrounds.

There are still many political prisoners inside the U.S. despite the “human rights” posture of successive administrations. Until the system of national oppression and capitalist exploitation is overthrown there is no hope for ending the prison-industrial complex.