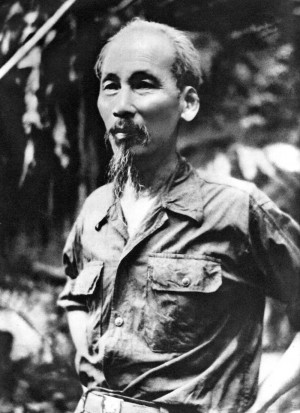

Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh: ‘On lynching & the Ku Klux Klan’

This May 19 will mark the 125th birthday anniversary of the great anti-imperialist leader, Ho Chi Minh. “Uncle Ho” was a leader of the National Liberation Front, a people’s army that defeated both French and U.S. military invaders in Vietnam. In honor of this legendary figure and the current Black Lives Matter uprising, WW is printing the following excerpts from a report made by this Vietnamese communist at the Fifth Congress of the Communist International gathering held in July 1924 in Moscow during the “National and Colonial Question” session. He died in 1969, six years before Vietnam’s liberation from U.S. imperialism. Go to tinyurl.com/n5nlck6 to read the entire report.

It is well-known that the Black race is the most oppressed and the most exploited of the human family. It is well-known that the spread of capitalism and the discovery of the New World had as an immediate result the rebirth of slavery. What everyone does not perhaps know is that after sixty-five years of so-called emancipation, American Negroes still endure atrocious moral and material sufferings, of which the most cruel and horrible is the custom of lynching.

[Charles] Lynch was the name of a planter in Virginia, a landlord and judge. Availing himself of the troubles of the War of Independence, he took the control of the whole district into his hands. He inflicted the most savage punishment, without trial or process of law, on Loyalists and Tories. Thanks to the slave traders, the Ku Klux Klan and other secret societies, the illegal and barbarous practice of lynching is spreading and continuing widely in the states of the American Union. It has become more inhuman since the emancipation of the Blacks, and is especially directed at the latter.

From 1899 to 1919, 2,600 Blacks were lynched, including 51 women and girls and ten former Great War soldiers.

Among 78 Blacks lynched in 1919, 11 were burned alive, three burned after having been killed, 31 shot, three tortured to death, one cut into pieces, one drowned and 11 put to death by various means.

Georgia heads the list with 22 victims. Mississippi follows with 12. Both have also three lynched soldiers to their credit.

Among the charges brought against the victims of 1919: one of having been a member of the League of Non-Partisans (independent farmers); one of having distributed revolutionary publications; one of expressing his opinion on lynchings too freely; one of having criticized the clashes between whites and Blacks in Chicago; one of having been known as a leader of the cause of the Blacks; and one for not getting out of the way and thus frightening a white child who was in a motorcar. In 1920, there were fifty lynchings, and in 1922 there were twenty-eight.

These crimes were all motivated by economic jealousy. Either the Negroes in the area were more prosperous than the whites, or the Black workers would not let themselves be exploited thoroughly. In all cases, the principal culprits were never troubled, for the simple reason that they were always incited, encouraged, spurred on and then protected by politicians, financiers and authorities, and above all, by the reactionary press.

The place of origin of the Ku Klux Klan is the southern United States. In May, 1866, after the Civil War, young people gathered together in a small locality of the state of Tennessee to set up a circle.

The victory of the federal government had just freed the Negroes and made them citizens. The agriculture of the South — deprived of its Black labor — was short of hands. Former landlords were exposed to ruin. The Klansmen proclaimed the principle of the supremacy of the white race. The agrarian and slaveholding bourgeoisie saw in the Klan a useful agent, almost a savior. They gave it all the help in their power. The Klan’s methods ranged from intimidation to murder.

The Negroes, having learned during the war that they are a force if united, are no longer allowing their kinsmen to be beaten or murdered with impunity. In July 1919, in Washington, they stood up to the Klan and a wild mob. The battle raged in the capital for four days. In August, they fought for five days against the Klan and the mob in Chicago. Seven regiments were mobilized to restore order. In September, the government was obliged to send federal troops to Omaha to put down similar strife. In various other states the Negroes defend themselves no less energetically.