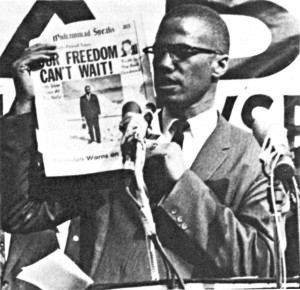

Malcolm X and global Black struggle

In March 1964, Malcolm X announced his official departure from the Nation of Islam. He had spent 12 years working on behalf of the organization led by Elijah Muhammad. Malcolm had been suspended and silenced for 90 days after he delivered an address at the Manhattan Center on Dec. 1, 1963, entitled “God’s Judgment of White America.”

This rally, organized by the NOI, was planned well in advance of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on Nov. 22 in Dallas. Muhammad had ordered all his ministers not to speak directly about the assassination since the country was still in a state of shock and mourning.

When Malcolm X was asked about the assassination, he noted that the U.S. government and its leaders had engaged in targeted assassinations of foreign leaders, specifically pointing to the murder of Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. The U.S. played a prominent role in the destabilization of Lumumba’s government in 1960, as well as his kidnapping, torture and execution in January 1961.

Malcolm said the Kennedy assassination was a “case of the chickens coming home to roost,” a common phrase in the African-American community suggesting that deeds committed against others will come back to haunt the perpetrators. At the conclusion of the 90-day suspension, the national headquarters of the NOI in Chicago sent word that the punishment for ostensibly violating discipline would be extended indefinitely.

Malcolm X called a press conference where he announced not only his departure from the NOI but also the establishment of another organization, the Muslim Mosque Inc. This religious group would also involve itself in electoral politics and community organizing.

For several years before his split with Muhammad and the NOI, Malcolm X had sought to build alliances among African Americans, Africans from the continent, and Muslim nations and communities outside the U.S. At his “Message to the Grassroots” speech in Detroit on Nov. 10, 1963, just three weeks prior to his suspension from the NOI, he said that genuine independence struggles were bloody and that the people of Algeria, Kenya, China and other countries only gained their independence and sovereignty because they were willing to engage in armed struggle. (Recording by the Afro-American Broadcasting Corporation in Detroit)

Malcolm X returned to Detroit in April 1964 to deliver his legendary “Ballot or Bullets” speech. “It’s freedom for everybody or freedom for nobody,” Malcolm X declared. He said that if African Americans were willing to fight on behalf of U.S. imperialism against armed revolutionaries in Vietnam and Korea, then there should be no problem with them taking up guns to defend themselves against the Ku Klux Klan and other racists in this country.

Travels to Mecca, African states

In May 1964 Malcolm X embarked upon the hajj, the religious pilgrimage that Muslims strive to have in their lifetime. Under the NOI, the hajj was not mandatory, and therefore the organization lacked what was perceived as authenticity in Islamic communities in the East.

After making his religious pilgrimage, he added El-Hajj to his existing Muslim name, Malik Shabazz, stressing his acceptance within the orthodox Muslim faith. During this trip Malcolm also traveled to several African states, including Egypt, Nigeria and Ghana.

He returned to the U.S. in June and founded a new political group, the Organization of Afro-American Unity. The group was patterned on the Organization of African Unity, the continental organization of independent states formed the year before in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Malcolm set out for the Second Annual Summit of the OAU in Cairo, Egypt, in July 1964 to make a direct appeal to African leaders for solidarity and support in resolving the plight of African Americans under U.S. national oppression.

In an eight-page memorandum to the African heads of state in Cairo, Malcolm X, writing on behalf of the OAAU, wrote: “Our problem is your problem. No matter how much independence Africans get here on the mother continent, unless you wear your national dress at all times when you visit America, you may be mistaken for one of us and suffer the same psychological and physical mutilation that is an everyday occurrence in our lives.”

He continued, “Our problem is your problem. It is not a Negro problem, nor an American problem. This is a world problem, a problem for humanity. It is not a problem of civil rights but a problem of human rights.”

Malcolm went even further, saying that the racist apartheid regime of South Africa at that time was less of a threat than the racist U.S. regime. He wrote, “America is worse than South Africa, because not only is America racist, but she is also deceitful and hypocritical. South Africa preaches segregation and practices segregation. She, at least, practices what she preaches. America preaches integration and practices segregation. She preaches one thing while deceitfully practicing another.”

Lessons from Malcolm X’s legacy

On his second visit to Africa and the Middle East in 1964, Malcolm X stayed outside the U.S. for four months, stopping over in France and England on his way back to enhance relations between African Americans and the African Diaspora in Western Europe.

After returning to the U.S., his speeches during rallies for the OAAU were often held at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, N.Y. He shared platforms with members of the Pan-African Students Organization of the Americas and other African leaders such as Tanzanian revolutionary Abdul Rahman Mohamed Babu, a Marxist and Pan-Africanist who advocated socialism as the only solution for the continent.

Malcolm X met with Che Guevara during his visit to the United Nations in December 1964. Guevara sent a statement of solidarity to an OAAU meeting that was read by Malcolm X.

On the eve of his assassination in February 1965, Malcolm attempted to enter France again but was denied entry. The French government would not provide a specific answer about why he was being denied admission.

Upon returning to the U.S., Malcolm’s home was bombed in the early morning hours of Feb. 14. He subsequently traveled to Detroit and delivered a speech encompassing themes of pan-Africanism and internationalism.

In one of his final addresses, delivered at the Corn Hill Methodist Church in Rochester, N.Y., on Feb. 16, Malcolm said that “in no time can you understand the problems between Black and white people here in Rochester or Black and white people in Mississippi or Black and white people in California, unless you understand the basic problem that exists between Black and white people — not confined to the local level, but confined to the international, global level on this earth today.”

Malcolm X was assassinated on Feb. 21 before he was able to address an OAAU audience at the Audubon Ballroom. Although his assassination had been attributed to members of the NOI, many since then believe that the federal government was behind his death in response to his uncompromising militancy and his political evolution toward revolutionary pan-Africanism and internationalism.

In addition to seeking the assistance of African governments and national liberation movements in the struggle of African Americans, Malcolm X, like William Patterson, Paul Robeson and W.E.B. Du Bois of the Civil Rights Congress in 1951, sought to take the plight of African Americans before the United Nations, seeking sanctions against the U.S. for crimes against humanity. Malcolm X also said that through his travels he keenly observed that the countries making the most progress were moving toward socialism and the liberation of women.

These words hold true today. The African and Middle Eastern communities in Europe have exploded in urban rebellions in the same way they developed inside the U.S. after 1963.

Until the system of international racism and economic exploitation is confronted by oppressed peoples collectively, on a global level, there will not be a solution to the crisis. Youth today must study the works of Malcolm X and apply the lessons of his life and struggles to the monumental challenges facing the workers and oppressed in the 21th century.