A fighter against war and racism

Muhammad Ali died June 3 after a decades-long battle against Parkinson’s disease.

In addition to being a phenomenal athlete, he made great contributions to the anti-war and anti-racist movements.

Ali, then known as Cassius Marcellus Clay, won the Chicago Golden Gloves title in amateur boxing in 1959 and 1960. In subsequent bouts, he won unanimous decisions over Gennady Shatkov of the Soviet Union and Tony Madigan of Australia, and then decisively beat favorite Zbigniew Pietrzykowski of Poland.

Clay, then 18, came to world attention in 1960 after winning a gold medal for the U.S. in light heavyweight boxing at the Rome Olympics. There, he won his first fight against Yvon Becot of Belgium.

In 1960, youth in the U.S. South initiated the sit-in movement, demanding an end to legalized segregation in restaurants and other commercial establishments. On Feb. 1, in Greensboro, N.C., four students from the North Carolina Agricultural and Industrial College, attended by African Americans, sat down at Woolworth’s Department store in a “whites only” section. They sparked a nationwide struggle. By April, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was formed.

This militance on social issues was matched by the strong, dominant presence of African-American athletes at the Olympic games in Rome in 1960. There, the advancements that African Americans made in international sports was highlighted. Their presence in the games directly challenged segregationists, who still controlled Southern and national politics.

The July 16, 2012, Examiner published during London’s Olympic Games recalled, “Not since Jesse Owens in the 1936 Summer Games in Germany had African-American athletes captured the Olympic world stage as in 1960. … Sprinter Wilma Rudolph was the first woman to win three Olympic Gold Medals. Decathlon Gold Medal winner Rafer Johnson was the first African-American Olympic Captain. African-American athletes won a total of 22 medals, 16 of which were gold.”

Becoming Muhammad Ali

After Clay won the heavyweight boxing championship against favored titleholder Sonny Liston on Feb. 25, 1964, he announced his membership in the Nation of Islam, and declared that his new name was Muhammad Ali. Consequently, he became a target for the ruling class and the corporate press.

Ali invited Malcolm X to Miami for the Clay vs. Liston fight. After returning to New York, Malcolm X took Ali on a tour of the United Nations and introduced him to African and other diplomats. In December 1963, Malcolm X had been silenced for 90 days by NOI leader, the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, over his “chickens-coming-home-to-roost” statement about President John F. Kennedy’s assassination.

Developments in March 1964 broke the relationship between Ali and Malcolm X. Chicago NOI headquarters informed Malcolm X of his indefinite suspension, and barred him from speaking at mosques or publicly on behalf of the organization that he had made famous worldwide.

Malcolm X announced at a March 12 press conference in Harlem that he was forming a separate mosque. His efforts took on a more direct political character when he asserted that the new Muslim Mosque, Inc. would engage in voter registration and perhaps form a Black political party.

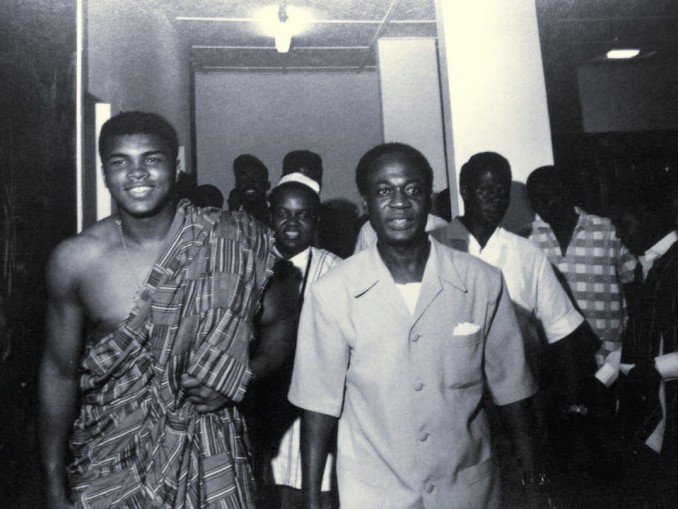

Ali and Malcolm X met for the last time publicly in Ghana in West Africa in May 1964, when the country was led by President Kwame Nkrumah, the founder of modern Africa and a proponent of Pan-Africanism and socialism. When encountering Malcolm in an Accra hotel, Ali refused to address him.

Acrimony between Malcolm X, who formed the Organization of Afro American Unity in June 1964, and the NOI escalated into an ideological and personal conflict. Relations were so strained that when Malcolm X was assassinated on Feb. 21, 1965, the federal government and corporate media tried to blame the NOI.

Resistance to the draft

Ali was drafted into the U.S. military in 1966 and refused induction in early 1967, saying he had no quarrels with the Vietnamese people. The boxing establishment took his title away, while the courts convicted him of violating the Selective Service Act and sentenced the champion to five years in prison. He remained free on bond, while appealing the sentence and speaking out across the country.

Ali’s stance was shared by thousands of African Americans, whites and others who objected to serving in a war of genocide against the Vietnamese people. The NOI and organizations in the struggle, such as SNCC and the Black Panther Party, opposed the war and pledged their solidarity with the National Liberation Front of Vietnam.

Ali won back his right to participate in professional boxing in 1970 when a ruling allowed him to fight again for the first time in over three years. By March 1971, he lost his title to Joe Frazier at New York’s Madison Square Garden. On June 28, the Supreme Court unanimously overturned Ali’s conviction for refusing the draft.

Ali regained the title in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) in October 1974, defeating George Foreman, the 1968 Olympic gold medal heavyweight boxing winner. Then, thousands of people from throughout Africa and the world visited the country. Famous Black artists, including James Brown, B.B. King, the O’Jays and Miriam Makeba, performed in several concerts.

Even though Zaire was a neocolonial outpost of reaction and counterrevolution across Africa, the African masses expressed their solidarity with Ali as illustrated in the documentary “When We Were Kings.”

Ali fought a victorious bout with Joe Frazier in the Philippines in 1975. His contests afterwards led to both victories and defeats before he retired in 1981.

The life of Muhammed Ali illustrates the role of African Americans in sports and its relationship to the broader struggle against national oppression. His death has highlighted the great contributions he made as an athlete and fighter against imperialist war and for social justice for oppressed peoples.