How Black workers were decimated by racism

Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder isn’t the only criminal who should be punished for lead poisoning Flint’s children. General Motors impoverished the Black majority city of Flint, Mich., by closing nine of the 10 plants it had there. GM owes billions in reparations.

Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder isn’t the only criminal who should be punished for lead poisoning Flint’s children. General Motors impoverished the Black majority city of Flint, Mich., by closing nine of the 10 plants it had there. GM owes billions in reparations.

Flint was the center of what was once the world’s largest manufacturing corporation. So why did GM slaughter Flint?

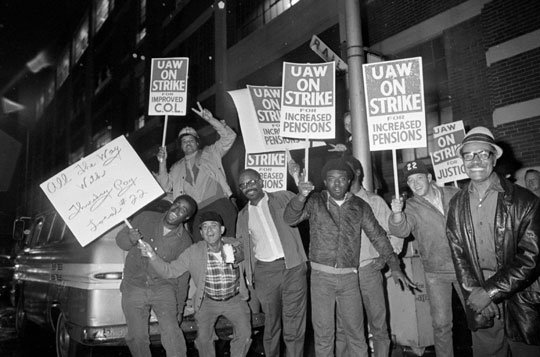

GM and other industrial giants wanted to end their dependence on Black labor. Forty-five years ago a quarter of the workers in U.S. steel mills and auto plants were African American. (“Organized Labor and the Black Worker,” by Philip Foner)

Malcolm X had worked at Detroit’s Lincoln-Mercury plant. So had Berry Gordy, the founder of Motown Records.

Deindustrialization wasn’t just the result of automation and superexploiting workers in other countries. It was also a political decision targeting Black workers.

Wall Street never forgot how African Americans shook auto plants in the 1960s and 1970s. The League of Revolutionary Black Workers led wildcats in Detroit. There was a Black Panther Party caucus in GM’s Fremont, Calif., plant.

“Like a tremendous explosive charge, the irresistible drive for Black freedom, a drive which necessarily includes all oppressed nationalities, is being brought into the plants,” was how Vince Copeland described this period in “Southern Populism and Black Labor.” Copeland was the founding editor of Workers World newspaper.

On July 24, 1973, two Black workers — Larry Carter and Isaac Shorter — turned off the power at Chrysler’s Jefferson Avenue plant in Detroit. This was the first big sit-down strike in 36 years.

Capitalism’s answer was to build most of the new auto plants away from large Black communities. This became standard practice starting in 1968, when GM opened its Lordstown, Ohio, plant.

The capitalist class economically destroyed Detroit, just as it let Black people drown and starve in New Orleans.

Chrysler got rid of 35,000 workers in Motown. From 1979 to 1982, Chrysler’s entire workforce went from 70 percent African-American to 30 percent.

Jails, not jobs

The wholesale destruction of heavy industry in the Midwest caused the median income of African Americans to drop by 36 percent between 1978 and 1982. (Census Bureau, Historical Tables) A reverse migration began back to the South.

The firing of hundreds of thousands of Black workers in auto, steel and other unionized occupations was accompanied by their wholesale incarceration.

Capitalism closed the factories and poured in drugs and guns. The 2.3 million prisoners in the U.S. are workers, too.

The racist character of new capitalist investment can be seen in Wisconsin.

Milwaukee County has large Black and Latino/a communities. Some 55,000 manufacturing jobs were destroyed there between 1977 and 1992, before the North American Free Trade Agreement was implemented. But the rest of the state, which with few exceptions is overwhelmingly white, gained 66,000 of these factory jobs. (Census of Manufactures)

Milwaukee’s Black community has never recovered from the closing of the A.O. Smith auto frame plant, American Motors and many other factories. One out of 25 African Americans in the Badger State is now in prison.

When Black workers matter, all workers matter

The attacks on Black workers were a defeat for the entire multinational working class. The United Auto Worker contracts that Black workers helped win through strikes became a standard for workers coast-to-coast.

Even workers in nonunion offices and other workplaces were to receive dental insurance and other benefits that came to be expected as part of the wage package.

The biggest reason for declining union membership was thousands of closed factories, many of which had large numbers of African-American workers.

The number of strikes involving more than a thousand workers fell from 424 in 1974 to a mere five in 2009. That’s a drop of 99 percent. (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

Militant labor organizer Al Stergar told this writer that 16 Black workers were the key to winning an organizing strike in his small Milwaukee sweatshop. Stergar was a Workers World Party leader who died in 1996.

Bosses knew that African Americans were the bedrock of union organizing campaigns. Clarence E. Elsas — owner of Atlanta’s now closed Fulton Industries bag and textile mills — admitted in 1962 that he didn’t hire Black workers in order to keep unions out. (“Hiring the Black Worker,” by Timothy Minchin) So even in the deep South of 54 years ago, bosses feared African Americans leading whites to a union.

The 1973 Detroit sit-down strike at Chrysler’s Jefferson Avenue plant sparked a revolt of Black and white, largely Polish-American, workers against unsafe working conditions at Chrysler’s Lynch Road Forge plant. (“Detroit: I Do Mind Dying,” by Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin)

Bosses put new factories and warehouses in locations like rural Wisconsin or just a mile beyond the last bus stop to avoid hiring Black workers. These tactics go hand-in-hand with staging ICE deportation raids against immigrant workers during union campaigns.

For decades, the largest private employer of African Americans was the Pullman Co., with its sleeping car porters. Later, U.S. Steel and then General Motors opened up their hiring and moved to first place, with Ford and Chrysler close behind. That was a quantum leap forward.

It’s a big step backward that the biggest employer of African Americans today is Walmart, with its poverty wages. Yet these “big box” stores represent a new concentration of workers that will inevitably force a union contract out of the Walton family and its $149 billion fortune.