Haitians remember U.S. invasion of 1915

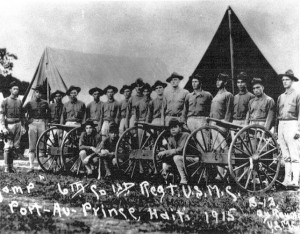

The United States began its military occupation of Haiti a century ago, sending an armed force ashore on July 28, 1915, just south of Port-au-Prince.

A bit earlier, a raiding party of U.S. Marines had stolen Haiti’s gold reserve of about $500,000 and turned it over to First National City Bank in New York — now Citibank.

In Haiti and its diaspora, activists held demonstrations and conferences to mark this hundred-year anniversary. In New York, a conference and cultural evening were held in the Haitian community and at John Jay College.

In Haiti and its diaspora, activists held demonstrations and conferences to mark this hundred-year anniversary. In New York, a conference and cultural evening were held in the Haitian community and at John Jay College.

Given the significance of the present mass expulsion of Haitians and Haitian-Dominicans from the Dominican Republic, some of the speeches were in Spanish while others were in Creole, French and English.

Historical background to the occupation

Haiti was the second country in the Western Hemisphere to gain its independence. After a hard-fought, 12-year-long struggle against France ended in 1804, slavery was eradicated and the slave owners expelled from the country.

The U.S. sent its first foreign aid — $750,000 worth of food and arms — to the slave owners in Haiti to put down the revolt. At that time, $750,000 was big money. The U.S. Constitution enshrined slavery and U.S. leaders held up Greece and Rome, whose economies and societies depended on slavery, as models for the state they were building.

The U.S. didn’t recognize Haiti as an independent country for 60 years, actively working to keep Haiti diplomatically and economically isolated. U.S. slave owners were extremely worried that Haiti’s example might be contagious, especially since 10,000 whites had fled from Haiti to the U.S.

Haiti’s “original sin,” in the opinion of many Haitian historians and activists, was becoming the only country to have had a successful slave revolution.

Opposition in both Haiti and U.S.

Justifications for the U.S. occupation, which lasted until 1934,were filled with lies and outright falsehoods. President Woodrow Wilson openly declared its purpose was to “establish peace and good order” and “has nothing to do with any diplomatic negotiations.” But his orders to the admiral running the operation involved changing Haitian law to protect U.S. and other foreign interests.

The U.S. invoked the Monroe Doctrine to justify its violation of Haitian sovereignty and forced the Haitian Parliament to agree to a 10-year treaty that made Haiti a U.S. political and financial protectorate.

The occupying Marine forces came from the U.S. South, where anti-Haitian sentiment and racism were at high levels. The Marines forced Haitian peasants, the vast majority of the population at that time, into work gangs to build roads, bridges and dams.

Their treatment was so rotten that it provided the impetus for a revolt of the cacos, armed peasant guerrillas, under the leadership of Charlemagne Péralte and Benoît Battraville. This revolt lasted, even after the execution of Péralte and Battraville, until 1921. Even after the end of the armed resistance, popular opposition, sparked by nationalist students and by the formation of the Haitian Communist Party under Jacques Roumain, intensified, until the U.S. finally withdrew its troops in 1934.

The first opposition in the United States came from the Black community and was part of the NAACP’s international work. According to Mary Renda’s book “Taking Haiti,” the U.S. Communist Party, mainly working through allied groups, played a prominent part in organizing this opposition. The occupation of Haiti, and of the Dominican Republic, were issues in the presidential campaigns of the 1920s.

Withdrawing U.S. Marines didn’t really end U.S. control over Haiti. The National Guard, which became the Haitian army, was formed and trained by the Pentagon. It supported the reign of the Duvaliers, father and son, from 1957 to 1986. It then sponsored, maneuvered and supported various military regimes until the elections that brought Jean-Bertrand Aristide into the presidency in 1991. It then supported and helped organize the two coups against him.

Since 2004, a United Nations military force called Minustah has occupied Haiti. It functions as a veil for U.S. troops, which could be quickly sent in if Washington felt it necessary. For example, 25,000 U.S. troops arrived in a few days after the earthquake of 2010 wiped out the U.N.’s command.

Beyond exercising military and political rule over Haiti, U.S. rulers want to humiliate it, pretending it can’t run its own affairs without outside assistance, and discount and deprecate its culture.

The Haitian progressive movement has organized protests of 100,000 people or more in Port-au-Prince and nationwide, even though most Haitians live without reliable electricity or telephone service. They can certainly organize themselves.

Their culture is alive and vibrant, as the poets and musicians who mixed Creole, French and English in their presentations in New York demonstrated. Long live a free and independent Haiti!

For more information, see the book “Haiti: A Slave Revolution,” which can be read online at http://www.iacenter.org/haiti/.