Septima Clark and the role of civil rights education in South Carolina and beyond

Since the massacre of nine African Americans at the Mother Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, we have reviewed the legacy of the Civil Rights struggle in Charleston, S.C., starting with Denmark Vesey and his comrades being targeted by the slavocracy for plotting insurrection in 1822.

A list of notable organizers in the African struggle against slavery and institutional racism from South Carolina must include AME Bishop Henry McNeal Turner (1834-1915). Turner rose to prominence as a soldier in the Union Army during the Civil War, a politician during Reconstruction and a proponent of Pan-Africanism during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Leading role of Septima Clark

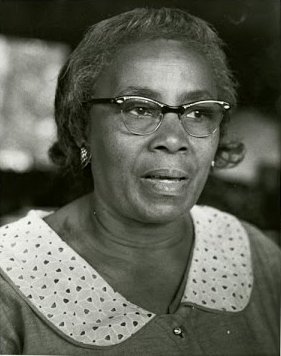

An often overlooked figure in the African-American movement was Septima Poinsette Clark. Born on May 3, 1898, in Charleston, she studied education and became a teacher.

Clark joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which during the early 20th century was considered a dangerous militant organization by the Southern ruling class. Legalized segregation was the law of the South and many areas of the North of the United States.

An entry published by biography.com says that “Clark qualified as a teacher, but Charleston did not hire African Americans to teach in its public schools. Instead, she became an instructor on South Carolina’s Johns Island in 1916. In 1919, Clark returned to Charleston to teach at the Avery Institute. She also joined with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in trying to get the city to hire African-American teachers. By gathering signatures in favor of the change, Clark helped ensure that the effort was successful.”

Septima Poinsette married Nerie Clark in 1920. He died of kidney failure five years later. She then relocated to Columbia, S.C., the state capital, and continued her education career.

There she joined the local chapter of the NAACP. Clark worked consistently with the organization along with attorney Thurgood Marshall, a leading activist who later was named a justice of the Supreme Court. In 1945, they initiated a legal case demanding equal pay for African-American and white teachers. Clark later described the case as her “first effort in a social action challenging the status quo.”

After winning the case, her salary as a teacher increased threefold. Similar cases were filed in various states throughout the South during the 1940s.

Clark then went back to Charleston in 1947, securing another teaching position and continuing her activism in the NAACP. Nonetheless, in 1956, the racist state government in South Carolina made it illegal for public employees to hold memberships in civil rights organizations. A principled organizer and fighter in the anti-racist movement, Clark refused to resign from the NAACP and consequently was fired from her job after decades of service.

Civil rights and mass education

Despite these setbacks, Clark continued her pioneering work in the Civil Rights movement, which was gaining mass support during the mid-to-late 1950s. She realized the necessity of adult literacy in the struggle for voting rights and advancement within the labor market.

After being terminated as a public school teacher in South Carolina, Clark went to work for Tennessee’s Highlander Folk School, an institution that trained organizers in the labor and the Civil Rights movements. She was no newcomer to the Highlander School, having led workshops there during breaks from teaching in South Carolina. Rosa Parks, popularly known as “the Mother of the Civil Rights Movement,” had attended workshops conducted by Clark in 1955 prior to the beginning of the Montgomery bus boycott later that same year.

Clark was appointed as the director of the Highlander’s Citizenship School program. This program assisted working people and farmers in learning how to instruct others in their communities in the fields of basic literacy and mathematics. As a result of these projects, more people were able to register to vote, since Southern states often utilized literacy tests to exclude African Americans from the franchise.

By 1961, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which was founded by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other ministers in 1957, adopted the education project. Clark soon joined the SCLC as its director of education and teaching. Under her direction, more than 800 citizenship schools were established.

Clark became the first woman to occupy a seat on the board of the SCLC. She had to deal with an organization which was male-dominated and still burdened with paternalism.

Another leading African-American woman organizer, Ella Baker, who had also worked with the NAACP during the 1930s and 1940s, served as the first executive director of the SCLC but left the organization after differences with its leaders. Baker convened the Southwide youth conference in April 1960 at Shaw College in Raleigh, N.C., which led to the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Significance of Septima Clark today

A pioneer in mass education, Clark’s work linked adult literacy to the struggle for civil rights and political representation. Political education is needed desperately in 2015 as African Americans renew the struggle against racism and for self-determination along with full equality.

Since the height of the Civil Rights movement, the ruling class has waged a campaign to reverse all the gains won during the period between the 1940s and 1970s. Today, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 has been stripped of its enforcement provisions, while in many states affirmative action programs designed to re-correct historic disparities in education, housing, employment and women’s rights have been eviscerated.

In order to wage these necessary struggles, workers, oppressed people and women must be organized and politically educated. A study and recognition of the lives and contributions of Septima Clark, Ella Baker, Rosa Parks and countless other African-American women would aid this effort.

Septima Clark died in 1987 after publishing two autobiographies, one in 1962 entitled “Echo in My Soul” and the other, “Ready From Within,” in 1987. Her legacy is well-secured within the history of the African-American people and all forces fighting for an end to racism and inequality.