African-American jockeys battle racism

The Saratoga Race Course in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2013. It opened in 1863, and became a summer getaway resort for tourists and wealthy socialites like the Vanderbilts and Rockefellers.

In Long Island, N.Y., horse racing dates back to 1665 and was the country’s initial pastime. During the Civil War, race tracks were closed down in the South, where horse racing had been quite popular. However, the sport was revived in the North; New York became the racing center.

Enslaved Africans on Southern plantations who worked in horse stables often trained horses and rode in informal races. In the early 1800s, horse racing became an organized sport. Black jockeys, the first professional athletes, came to dominate horse racing for two centuries. The earliest known Black jockey star in the 1800s was only known as “Simon.”

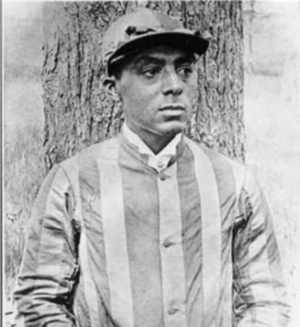

Black jockey Isaac Burns was born on a Kentucky farm in 1861. His father was a free Black man and bricklayer, who joined the Union Army and died in a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp during the Civil War. As a tribute to his grandfather, Green Murphy, Burns changed his name to Murphy when he started racing horses.

America Burns, Murphy’s mother, worked at a stable in Lexington, Ky. There, Eli Jordan, a Black trainer, prepared Murphy for his first race in 1875. By the end of 1876, he had won 11 races.

In the first Kentucky Derby, held in 1875 at Churchill Downs in Lexington, 13 of the 15 jockeys were African Americans. From then until 1902, more than half of the winning horses at the Derby were ridden by African-American jockeys.

Murphy’s win in 1879 at the Saratoga Race Course brought him national attention. In 1884, he won first place in the Kentucky Derby. Subsequently, he won the American Derby four times in Chicago. In 1890, after winning a race against a white jockey, racial hatred caused his popularity to fall, and he was forced to retire in 1895.

Murphy was the first jockey to win the Kentucky Derby three times. He had the best winning average in history. In 1955, he became the first Black jockey to be inducted into the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in Saratoga Springs. The second Black jockey to be so recognized posthumously was Willie Simms in 1977. He had won the Kentucky Derby in 1896 and 1898.

Jimmy Winkfield, an African American, born in 1882 in Kentucky, was a self-taught jockey. His father was a sharecropper and had watched thoroughbreds parade down the roads. Winkfield jumped fences, chased horses and rode them bareback.

In 1898, at age 16, Winkfield rode his first race in Chicago. A year later, he rode in the Kentucky Derby and won the race back-to-back: in 1901, at age 19, and then again the following year. In 1902, he was the last African American to win the Kentucky Derby. Winkfield was one of only five men, including Murphy, to win the Kentucky Derby in consecutive years — marks of best career performances.

Racism drove Black jockeys off the race tracks

In the early 1900s, opportunities for Black jockeys began to disappear. White horse owners and trainers preferred white jockeys. On the tracks, Winkfield became the target of racism by white jockeys. He also received death threats from the Ku Klux Klan. He fled to Europe, where he won horse riding championships in Russia, Poland, Germany and France.

In 1941, following Germany’s invasion of France, Winkfield returned to the U.S., where he became a horse groomer and trainer. In 1953, he returned to France and opened a jockey training school.

In 1961, Winkfield returned to the U.S. to watch the Kentucky Derby. However, when he and his daughter, Liliane Casey, arrived at the race course, they were told they could not enter through the front door. Once inside, nobody spoke to them.

Winkfield died in France in 1974. In 2004, he was posthumously inducted into the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame.

Joe Drape stated in “Black Maestro: The Epic Life of an American Legend,” his biography of Winkfield, that the jockey’s skill was secondary to his skin color: “An Anti-Colored Union was in place, with the goal of running black riders off the racetrack. It had begun earlier in the year at the Queens County track when the white jockeys … put the word out that if owners wanted to take home first-place purses, they’d best not ride the colored jockeys.”

The book notes, “Sometimes [the white jockeys] pocketed, or surrounded, a black jockey until they could ride him into and over the rail. Their whips found the thighs, hands, and face of the colored boy next to them more often than the horse they were riding. Every day a black rider ended up in the dirt; and every day racing officials looked the other way.” (William Morrow/HarperCollins, 2006)

From the early 1900s through the late 1940s, Black jockeys were excluded from major tracks in the Jim Crow South. Beginning in 1908, anti-gambling legislative bills led to shutdowns of race tracks. In New York, the tracks were closed in 1911. But when they reopened in 1913, notable African-American jockeys did not return. Black jockeys, in general, began to disappear. Racial prejudice drove nearly every Black jockey out of the profession.

Arthur Ashe, the late Black professional tennis player, said: “The sport of horse racing is the only instance where the participation of Blacks stopped almost completely while the sport itself continued — a sad commentary on American life. … Isaac Murphy, so highly admired during his time for his skills and character, would have been ashamed of his sport.” (Edward Hotaling, “They’re Off! Horse Racing at Saratoga.” Syracuse University Press, 1995)