‘Scottsboro Boys’: A 1931 case of legal lynching revisited

The documentary film, “The Central Park 5,” is showing in theaters here even as a federal civil rights lawsuit regarding the case proceeds against the city of New York and its police department. One is reminded of the case of the “Scottsboro Boys.” In both instances, innocent Black teenagers were falsely accused, convicted and imprisoned for raping a white woman, without any physical evidence to prove their guilt.

The documentary film, “The Central Park 5,” is showing in theaters here even as a federal civil rights lawsuit regarding the case proceeds against the city of New York and its police department. One is reminded of the case of the “Scottsboro Boys.” In both instances, innocent Black teenagers were falsely accused, convicted and imprisoned for raping a white woman, without any physical evidence to prove their guilt.

The Central Park 5 served between 7 to 13 years in prison for the 1989 crime. In 2002, they were exonerated after the actual serial rapist confessed and his DNA matched that of the attacker. However, there still is no closure in the Central Park 5 case, as their 2005 civil rights lawsuit is still pending in federal court. The Five, now in their thirties, are still awaiting justice and reparations. For them, the struggle continues.

Nothing apparently has been learned from the past. The structure of inequality remains intact. The case of the “Scottsboro Boys” was recognized as a horrific travesty of justice, one that many assumed could never happen again. But U.S. history continues to be replete with similar cases. Both the Scottsboro and Central Park 5 stories are powerful reminders of what can happen when the justice system is manipulated, the truth is ignored, and racism dominates.

Nothing apparently has been learned from the past. The structure of inequality remains intact. The case of the “Scottsboro Boys” was recognized as a horrific travesty of justice, one that many assumed could never happen again. But U.S. history continues to be replete with similar cases. Both the Scottsboro and Central Park 5 stories are powerful reminders of what can happen when the justice system is manipulated, the truth is ignored, and racism dominates.

Scottsboro case

In the Deep South of the 1930s, juries were unwilling to accord Black men charged with raping white women the usual presumption of innocence. Instead, just as in the Central Park case 58 years later, Blacks were declared guilty until proven innocent beyond a reasonable doubt. Black lives didn’t count for much. White supremacist ideology encompasses indifference to human consequences, then and now. Self-serving groundless accusations were allowed to change forever the lives of both the Scottsboro and the Central Park teens, who merely found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The crime the Scottsboro youth were accused of never actually occurred. Nevertheless, they were tried, convicted and imprisoned on death row, despite an abundance of evidence proving their innocence. It was said at the time that no other case had ever resulted in as many trials, convictions, reversals of decisions and retrials.

For nearly two decades, the youth struggled for justice. Their civil rights case was a story of racism, injustice and bigotry played out in the rigidly segregated South. They became victims of a racist legal system, spending the balance of their teen years into adulthood in jail paying for a crime they never committed, which is also the case with the Central Park 5.

On March 25, 1931, the nine innocent African-American teenage males from Georgia and Tennessee, ages 12 to 18, were falsely accused of gang raping at gunpoint two young white women aboard a Southern Railroad “hobo” freight train. Haywood Patterson, Roy Wright, Andy Wright, Charlie Weems, Clarence Norris, Ozzie Powell, Willie Roberson, Olen Montgomery and Eugene Williams were among the men, Black and white, who were riding the train in search of jobs. The two female accusers, Ruby Bates and Victoria Price, were mill workers from Huntsville, Ala.

A racial fight broke out on the train, causing the motorman to wire ahead to the next station, where an armed mob of white men was waiting. The teens were arrested and taken to a jail in Scottsboro, Ala., a small, rural town. That night, a lynch mob of several hundred surrounded the jail, but was thwarted by the National Guard. The teens became known as “the Scottsboro Boys.”

All but three of the youth denied raping or having even seen the two girls on the train. The three who confessed did so after repeated beatings and threats. Similarly, the Central Park teens suffered up to 30 straight hours of questioning and coerced confessions.

As their trial date approached, the Scottsboro teens were moved to a rat-infested Decatur, Ga., jail that had been condemned as “unfit for white prisoners.” Trials of the Scottsboro youth began just 12 days after their arrest. But local newspapers had already tried and convicted them, with calls for the death penalty, just as in the Central Park 5 case.

The girls’ stories were implausible and contradictory, with no evidence supporting their accusations of being gang raped. They lied because they feared being arrested under the Mann Act, which made it illegal to cross state lines for immoral reasons.

An unprepared, unpaid, alcoholic real estate attorney and an elderly, forgetful, retired attorney were assigned to represent the youth. The prosecution tried them in groups of two or three. No closing arguments were offered by these defense attorneys. The “Scottsboro Boys” were found guilty of rape and received the death penalty.

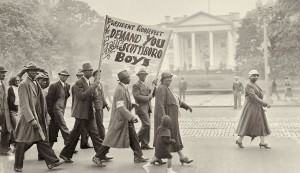

Because rape of white women, particularly in the South, was a volatile issue and remains so throughout the country, the NAACP did not readily come forth. But the Communist Party did, and zealously took on the case. The party’s International Labor Defense (ILD) attorneys described the case against the “Boys” as “a murderous frame-up.”

The ILD chose Samuel Leibowitz, a famous, winning New York criminal attorney, as the lead attorney and Joseph Brodsky of the ILD to assist. Leibowitz made a motion to crush the indictments and declare a mistrial on the grounds that Blacks were systematically excluded from jury rolls and that verdicts were based on racial prejudice. In 1933, a judge set aside the verdicts and ordered a new trial. The new jury also quickly returned a guilty verdict and sentenced them to death.

Between their first and second trials, the teens spent two years on death row in a deplorable Alabama prison. While on death row, they saw inmates being carried off to a death chamber near their cell and could hear the sound of the electrocutions. One of Haywood Patterson’s jobs was to carry out the bodies of electrocuted inmates.

Leibowitz appealed the convictions and sentences to the Alabama State Supreme Court, which upheld the verdicts. But on appeal to the U.S. Federal Supreme Court, it was ruled that the right of the defendants under the 14th Amendment’s due process clause to competent legal counsel had been denied, and the convictions were overturned. Again, new trials were ordered.

One of the accusers, Ruby Bates, later recanted her story, admitting that both women had lied. Afterwards, she became a leading Communist Party ILD spokesperson at Scottsboro rallies, where she begged forgiveness and pleaded for justice for the “Boys.”

The Alabama state attorney general announced that the state was convinced of the Scottsboro youths’ guilt. One trial judge, while instructing the jury, said they should presume that no white woman in Alabama would willingly consent to sex with a Black man. The same thinking operated in the Central Park 5 case.

Leibowitz appealed the death penalty to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that all the convictions should be overturned because Alabama systematically excluded Blacks from its jury rolls, which violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution, and that the verdicts were based on racial prejudice. In 1935, the court agreed and reversed the convictions of Clarence Norris and Haywood Patterson. New trials were again ordered.

An appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court also resulted in a ruling against the conviction of Eugene Williams and Ozzie Powell, stating they should not have been tried as adults. This was a landmark decision.

In 1937, the fourth and last trial of Haywood Patterson again resulted in a conviction for rape, but this time he was sentenced to 75 years. It was the first time in Alabama’s history that a Black man convicted of raping a white woman had not been sentenced to death.

Eventually, all death sentences were set aside and lengthy prison terms imposed instead, varying up to 99 years. Four of the “Scottsboro Boys” were exonerated, two because they were only 12 and 13 years old at the time of their conviction and had already served sufficient time. By 1946, four were paroled, but one was sent back to jail for a parole violation.

Haywood Patterson managed to escape in 1948. While a fugitive, he co-wrote his autobiography, “Scottsboro Boy: The Story That America Wanted to Forget.” It was published in 1950. Shortly afterwards, he was arrested by the FBI in Michigan, but the governor refused Alabama’s extradition request. Subsequently, Patterson’s rape conviction was overturned. Unfortunately, he was again imprisoned, where he died.

Though the others were finally free, they wore the label of being a “Scottsboro Boy” and suffered from psychological wounds inflicted during their years in prison and demons with which they had to contend. They struggled with life in the hellholes of prison and on the outside as well. As have the Central Park 5.

In 1979, Clarence Norris’ co-written autobiography, “The Last of the Scottsboro Boys,” was published. All have since died. None ever received an apology or financial restitution from the state of Alabama — much like the situation of the Central Park 5 to date.