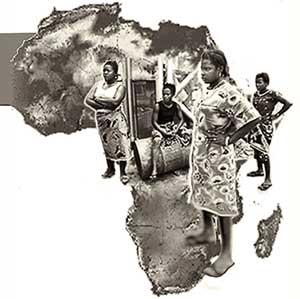

Women at forefront of Africa’s liberation struggles

By

Abayomi Azikiwe

Editor, Pan-African News Wire

Published Aug 13, 2010 10:27 AM

Many articles have been written reflecting on five decades of historical

experience — referred to as the 50th anniversary of the “Year of

Africa” — since 17 African nations gained political independence.

Yet few pay adequate attention to the indispensable role of women in the

campaigns for national liberation and their continuing efforts in the present

century.

On Aug. 9, 1956, some 20,000 women in South Africa marched from various regions

to the apartheid capital of Pretoria. They represented a cross-section of

women, most of whom were African, who resided and worked in both urban and

rural areas of the country.

Throughout the 20th century women in South Africa resisted the policies of the

European settler-colonial rule under both British and Boer domination. As early

as 1908, African women fought against racist laws that prohibited the brewing

and distribution of traditional beverages, outlawed so that the men could be

lured into beer halls and drained of their wage earnings.

Women boycotted and picketed the beer halls, forcing many to close. They

demanded that profits from the establishments be utilized to develop housing

and amenities for the African people relegated to the townships by the racist

colonial system.

Indeed, it was the women-initiated struggle against the pass laws that sparked

a broad-based mass movement during the 1950s. The major demand of the

women’s march on Pretoria was to abolish the passes that controlled the

movement of Africans inside their own country.

“In 1952, passes were extended to African women throughout the country.

Up to 1918, when they had been withdrawn in the face of stringent resistance,

they had been applied to African and Colored women in the Orange Free State

alone,” writes researcher Fatima Meer in “Women in Apartheid

Society.” (reprinted in Pambana Journal, February 1986)

Meer then points out the underlying reason for the enforcement of the apartheid

pass laws: “The intention was to contain the women in the reserves, to

leave them there to starve with their dependents, the unemployable young, the

sick and the old.”

This women-led struggle against the pass laws was protracted. Meer recounts:

“There was spontaneous resistance to the imposition of passes throughout

the country and the resistance continued for eight years. Thousands of women

were repeatedly imprisoned. In 1954, 2,000 were arrested in Johannesburg, 4,000

in Pretoria, 1,200 in Germiston, and 350 in Bethlehem. In 1955, 2,000 women

marched to the Native Commission’s office in Vereeniging.”

The African National Congress Women’s League, founded in 1943, was the

most prominent organization in this movement against pass laws, using its

branches throughout the country to build a national campaign.

Women from both the Natal Indian Congress and the ANC combined forces and

formed a broader organization. Both organizations were at the core of the 1954

founding of the Federation of South African Women, which played an integral

part in the Campaign of Defiance of Unjust Laws that lasted from 1952-1956.

In 1960 the ANC Women’s League organized a demonstration of both women

and children who were family members of those detained during the state of

emergency in Durban. During this demonstration some 60 women and children were

arrested and imprisoned.

The ANC Women’s League was banned alongside the parent organization after

the apartheid police opened fire on demonstrators, killing 69 and wounding

nearly 200 in what became known as the Sharpeville Massacre of March 21, 1960.

Nonetheless, this tradition of struggle was to carry over through the 1980s and

1990s. In 1994 the masses of workers and youth were able to overturn the racist

apartheid system.

Women and the movement for African unity & socialism

Women’s struggles like those in South Africa took place in various forms

in many African states from the 1950s through the early 1990s, when the last

vestiges of white-minority rule were eliminated in southern Africa. A major

effort took place in 1960 when the All-African Women’s Conference (AAWC)

was formed in Accra, Ghana.

Ghana in 1960 was considered the fountainhead of national independence and

Pan-Africanism. Kwame Nkrumah, the leader of the Convention People’s

Party, relied heavily on women in the urban and rural areas during the struggle

for independence and the postcolonial period.

C.L.R. James in his book “Nkrumah and the Ghana Revolution” noted

that “in the struggle for independence, one market woman ... was worth

any dozen Achimota [college] graduates. ... ”

A writer on the CPP-ruled era in Ghana history wrote of women inside the party:

“Together with the workers, young men educated in primary schools and the

unemployed, women became some of Nkrumah’s ablest, most devoted and most

fearless supporters.” (Kwame Arhin, “The Life and Work of Kwame

Nkrumah)

The Women’s Section of the CPP was formed simultaneously with the party

itself. The CPP provided opportunities for the wider involvement of women in

politics inside the then Gold Coast (later known as Ghana). In 1951, the CPP

selected Leticia Quake, Hanna Cudjoe, Ama Nkrumah and Madam Sohia Doku as

propaganda secretaries who traveled around the country conducting political

education meetings and recruiting people into the party.

By the time of independence in 1957, women such as Mabel Dove, Ruth Botsio, Ama

Nkrumah, Ramatu Baba, Sophia Doku and Dr. Evelyn Amarteifio were playing

leading roles as organizers, politicians and journalists. In 1960 they

consolidated the various women’s mass organizations into the National

Council of Ghana Women.

After Ghana became a republic in July 1960, the Conference of Women of Africa

and of African Descent was convened in Accra, the capital. Nkrumah addressed

the gathering, saying, “Who would have thought that in the year of 1960,

it would be possible to even hold a conference of all Ghanaian women, much less

of women of all Africa and women of African descent?” (Evening News,

Ghana, July 19, 1960)

Nkrumah then asked: “What part can the women of Africa and the women of

African descent play in the struggle for African emancipation? You must ask

these questions not by word of mouth but by action — by positive action,

which is the only language understood by the detractors of African

freedom.”

Shirley Graham DuBois, the spouse of W.E.B. DuBois and an accomplished writer,

organizer and committed socialist in her own right, was in Ghana at the time of

the founding of the First Republic and the inauguration of the NCGW and the

AAWC. She stated in an address before the Women Association of the Socialist

Students Organizations in Ghana that “the advancement of Ghanaian women

in recent years has been amazing and now with ten women Parliamentarians in

Republican Ghana, this country had achieved what took Europe centuries to

accomplish.” (Evening News, July 14, 1960)

In supporting the then movement toward socialism in Ghana, DuBois recounted her

travels to the People’s Republic of China and the achievements of women

since the revolution of 1949. She claimed in her address that “the women

of Socialist China were advanced in all spheres of useful activity and enjoyed

equal rights with men politically, economically, culturally, socially and

domestically.”

Women went on to play pioneering roles in other African liberation struggles in

Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Algeria, Tanzania, Guinea, Nigeria and

Sierra Leone as well as many other states. At the present time, the African

Union has declared 2010 the beginning of the “Decade of Women

(2010-2020)” on the continent.

Challenging gender inequality

At the recent annual summit of the African Union, the overall theme of the

gathering was initially focused on the status of maternal health and children.

Under pressure from his U.S. imperialist backers, Ugandan President Yoweri

Museveni tried to redirect the emphasis of the summit to carrying out

Washington’s foreign policy objectives in Africa.

The social dynamics of the world economic crisis have impacted Africa and

forced an estimated 50 million people into poverty. The continuing influence of

capitalist economic policies on Africa is a direct result of the subordinate

integration of the continent’s productive forces to the imperatives of

the multinational corporations and financial institutions.

To fully challenge gender inequality and the impoverishment of women and

children in Africa, the struggle must be directed against Western domination

and capitalist relations of production. This struggle in Africa can be

supported by anti-imperialist forces in the industrialized states when they

demand that their own imperialist governments honor the right of

self-determination and sovereignty of the oppressed, postcolonial nations.

Articles copyright 1995-2012 Workers World.

Verbatim copying and distribution of this entire article is permitted in any medium without royalty provided this notice is preserved.

Workers World, 55 W. 17 St., NY, NY 10011

Email:

ww@workers.org

Subscribe

wwnews-subscribe@workersworld.net

Support independent news

DONATE