LABOR HISTORY

70 years ago workers won Flint sit-down strike

By

Martha Grevatt

Published Feb 28, 2007 12:50 AM

1937 FLINT SIT-DOWN LABOR HISTORY SERIES

PARTS: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

In “The Threepenny Opera,” Bertolt Brecht asks the question,

“What is the crime of robbing a bank compared to the crime of owning a

bank?” A play about the Great Sit-Down Strike—Feb. 11 was the

70th anniversary of its triumphant conclusion—might ask the question,

“What is the crime of seizing the plants compared to the crime of owning

the plants?”

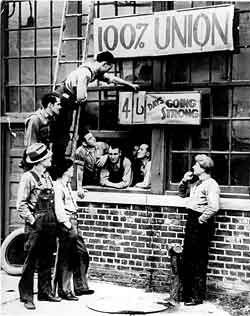

|

Flint strike.

Photos: www.uaw.org

|

In 1936, 43 percent of the U.S. automobile industry belonged to General Motors.

Its profits for that year totaled nearly $284 million. Its

assets—including 69 plants in 35 states—were valued at $1.5

billion. The company had 37 percent of the worldwide car and truck market. GM

President Alfred P. Sloan was the highest paid executive in the country.

GM would tout their claim that wages were high—$1,500 a year. The United

Auto Workers disputed those figures, citing the irregularity of the work. Laid

off workers were forced to take out loans from the company, with payments

deducted from their wages upon return to work. To avoid layoffs, you might get

to work on the boss’s house or, if you were a part-time farmer, bring him

some meat or produce.

|

The UAW Women’s Emergency Brigade.

|

The assembly line was a living hell. The ever-increasing pace of the

line—the speedup—gave many workers the appearance of a 50-year-old

before turning 30. A sit-down participant described “hands so swollen I

couldn’t get my fingers between each other.” A sociologist of the

time observed “occupational psychosis” from the monotony and

overwork.

The pain was felt deeply in Flint, Mich., home of GM and a quintessential

company town. Of the 146,000 residents, 44,000 worked for GM. There was no

company store, but that was the only company thing you didn’t “owe

your soul to.” Before GM’s arrival it was a town of 14,000

concentrated around carriage-building. Housing construction didn’t keep

up with population growth; many autoworkers lived in tar paper shacks without

indoor plumbing and others were forced to rent from GM.

No wonder then that the wave of sit-down strikes sweeping the U.S. in 1936

would culminate in a 44-day occupation in Flint.

|

Strikers inside the plant.

|

The sit-down strike was not invented in 1936. It was reportedly used in 15th

and 18th century France, early 19th century England and even in ancient Egypt

by a group of stonemasons. The early part of the 20th century saw occasional

sit-downs in the U.S., France, Italy, Yugoslavia, Spain, England, Wales and

Poland.

In the 1930s, a decade defined by class warfare, 1936 was the pivotal year when

the sit-down made the transition from a little-used tool to the key weapon.

Akron, according to Jeremy Brecher in his book “Strike!” “was

the crucible in which it was forged.” Rubber workers got the idea after

two union baseball teams sat down on the field, demanding a non-union umpire be

ejected and a union ump be brought in. On Jan. 29, 1936, workers sat down at

Firestone. When the plant went silent, they screamed “We done it!”

Two days later they sat down at Goodyear, days later at Goodrich. Another

sit-down at Goodyear, and then all of Goodyear was on strike. The strike ended

in victory March 18. Sitting down became a more or less weekly affair in Akron.

It then swept the nation, with 48 sit-downs recorded in 1936, most of them

lasting more than 24 hours.

Sit-downs were also spreading through France like wildfire. The June 22, 1936,

edition of Time magazine reported “8,000 Paris slaughterhouse employees

walked out. Clerks of all Paris’ great department stores continued their

‘stay in strikes.’ The world-famed dressmaking houses had to close.

Guests made their own beds in hostelries as various as the ultra-conservative

Grand Hôtel and the swanksters’ Hôtel Georges V. Outside Paris,

for every strike settled when the week opened, another was declared.”

Meanwhile 30,000 factory workers at Renault and an equal number at Citroën

were returning to work, having won all their demands. That same year the French

government reduced the standard workweek from 48 to 40 hours and made two weeks

vacation mandatory.

Radicals in the labor movement—members of the Socialist, Communist, and

other working class parties—saw the critical importance of organizing the

hundreds of thousands working in the automobile industry. They knew that they

had to crack the mighty General Motors and they had to hit key plants where it

would hurt the most.

One such plant was the Fisher body plant in Cleveland, and on Dec. 28, 1936, a

sit-down of 7,000 silenced the noisy presses. Two days later the strike moved

outside, joining strikes already going on in Atlanta and Kansas City. Now it

was time to take on Flint. A dress rehearsal had already taken place at the

strategic Fisher Body One; a brief sit-down won the rehiring of three fired

workers.

On Dec. 30 rumor spread that dies, the tools that stamp out body parts, were

being shipped out. A lunchtime meeting on the evening shift drew a huge crowd.

When the union organizer, Bob Travis, asked what ought to be done, cries rang

out: “Shut her down.” Before the shift was over the plant was in

the hands of the workers. The smaller Fisher Two was also taken that same

night.

Thousands of workers created their own community. Perhaps some of their more

class-conscious leaders had read about and were inspired by the Paris Commune.

Decisions were made democratically at the nightly strike meeting. There were

committees for everything from defense to entertainment and education. Many

line workers had never felt so alive.

Their baptism by fire came on Jan. 11, 1937, when guards at Fisher Two refused

to allow food in. Outside pickets brought food in by ladder to the second

floor, but the guards then confiscated the ladder. Then the police began to

surround the plant. Pickets swarmed to the gate. Twenty inside strikers, with

homemade clubs, demanded the guards open the gate. When the guards refused,

they forced the gate open. The police fired tear gas and vomit-inducing gas (of

which GM had its own private stockpiles).

The union sound car called on pickets to hold their posts and those inside to

grab the fire hoses. The cops were driven away by the force of the hoses and a

rain of two-pound hinges. Before they left they shot and wounded 14, including

a striking bus driver picketing with the autoworkers. This episode became know

as the “Battle of Bulls’ Run,” because, as one striker

recounted, “I never saw cops run so fast.”

Now GM was feigning a willingness to talk things out. By 3 a.m. on Jan. 15,

Michigan Gov. Frank Murphy announced “a peace.” The union agreed to

evacuate the plants, which by now included several in Detroit and Indiana, and

the company agreed not to resume production. The plants outside of Flint were

emptied of strikers and a big celebration was planned.

Before the celebration could take place, word of a double-cross was leaked to

the union by a sympathetic reporter. GM’s Vice President Knudsen had

agreed to meet with the union-busting “Flint Alliance” to discuss

“collective bargaining”—thus removing the union as the sole

bargaining agent. The city manager was deputizing Alliance members, creating a

vigilante force to compel a back-to-work movement. The evacuation of Fisher One

and Two was called off.

Now the union needed to gain some ground to break the stalemate. They wanted to

take Chevrolet Four, a critical plant, but it was heavily guarded. In a gamble

that would prove successful, they chose to occupy Chevrolet Nine, and to leak

word of the occupation to draw the guards away from Chevy Four. After being

told at a meeting they were needed at Chevy Nine, scores of pickets, half of

them from the Women’s Auxiliary and the Women’s Emergency Brigade,

converged on the plant. When the cops fired gas into the plant, attempting to

smother its occupants, the women smashed the windows to allow the gas to

escape. Combat with the police left many strikers bloodied and bruised, but the

police retreated in the face of such determination.

Not long after, a call to the union hall announced that Chevy Four had been

taken. Within hours, the Michigan National Guard descended upon Flint. The

union held strong and responded to a court injunction to evacuate by declaring

“Women’s Day.” Women came from all over Detroit, Toledo,

other parts of Ohio and elsewhere, and their parade became the longest (end to

end) picket line in Flint history.

On Feb. 10 GM finally signed an initial agreement to recognize the UAW as the

sole bargaining agent, for a period of six months, at the most important

plants. This initial victory would lay the foundation for the many gains that

followed.

On Feb. 11, 1937, after 44 days, the strikers marched out, leading a two-mile

parade that was joined by thousands and thousands. Relations between labor and

capital would never be the same.

1937 FLINT SIT-DOWN LABOR HISTORY SERIES

PARTS: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Articles copyright 1995-2012 Workers World.

Verbatim copying and distribution of this entire article is permitted in any medium without royalty provided this notice is preserved.

Workers World, 55 W. 17 St., NY, NY 10011

Email:

ww@workers.org

Subscribe

wwnews-subscribe@workersworld.net

Support independent news

DONATE